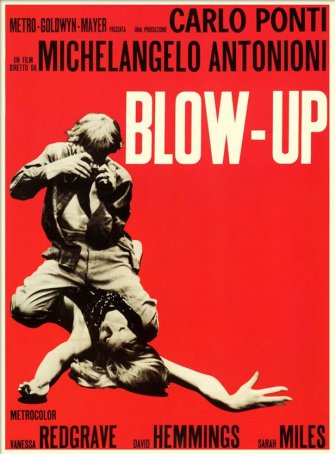

Blow-Up (Italy/United Kingdom/United States, 1966)

February 16, 2020

Audiences today might be tempted to label Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up as a “thriller that doesn’t deliver.” There’s some validity to that charge – if what one expects from a murder mystery is a resolution to the whodunnit? aspect, Blow-Up will disappoint. Expectations play a big part in how an unconventional movie, especially one without a clean, unambiguous ending, is received. In 1999, John Sayles released Limbo, a divisive movie that earned its title. For the most part, audiences hated the ending which, in spirit if not in the particulars, was similar to that of Blow-Up. Today’s viewers have been conditioned about what is deemed acceptable and the lack of a satisfying ending, even if there are specific reasons for it, is likely to create a sense of ire.

Putting aside the ending, the film has narrative shortcomings that cause it to fall short of its reputation. The film’s first half contains several self-indulgent passages and the Yardbirds concert sequence late in the proceedings (followed by a “drug party”) feels overlong and extraneous. In his mostly positive contemporaneous review of Blow-Up, legendary New York Times critic Bosley Crowther put his finger on the movie’s glaring problem, citing the “redundant…” “passages of seemingly endless wanderings.” Pauline Kael, in a pan, remarked that “[the ending] reminds one of so many naively bad experimental films” and characterized it as “a mixture of suspense with vagueness and confusion.” She compares Antonioni with Warhol, saying he’s “more interested in getting pretty pictures than in what they mean.” So, although the weight of critical opinion over the years has tilted positive for Blow-Up, it is by no means unanimous.

The central conceit – that of a high-profile fashion

photographer accidentally capturing a murder on film – has been appropriated

for a variety of films over the years. Arguably the best of these is an early

Brian De Palma production, Blow-Out, which replaced visual elements with

audio ones. Blow-Up is taut and suspenseful, although the movie’s lack

of a strong ending undercuts the tension somewhat.

The central conceit – that of a high-profile fashion

photographer accidentally capturing a murder on film – has been appropriated

for a variety of films over the years. Arguably the best of these is an early

Brian De Palma production, Blow-Out, which replaced visual elements with

audio ones. Blow-Up is taut and suspenseful, although the movie’s lack

of a strong ending undercuts the tension somewhat.

For anyone watching it during the early decades of the 21st century, Blow-Up provides a first-hand perspective of Swinging London of the 1960s. The point-of-view is so central to the film’s DNA that it at times overwhelms everything else and, because it was made in the moment rather than looking back, there’s a purity to the vision that is found in few other movies (especially period pieces set in the 1960s, which have a tendency toward parody á là the Austin Powers series). The lengthy opening sequences, which introduce us to photographer Thomas (David Hemmings) and accompany him on a shoot of fashion model Veruschka von Lehndorff, may be more fascinating for audiences today than they were to those watching the film in 1966 because of the window they open on a culture that has metamorphosed multiple times during the last 50+ years.

Thomas’ life seemingly consists of two components: work and

partying. He does both in a mechanical fashion that shows how detached he has

become from his everyday existence. One day while at a park, he has an odd

encounter with a woman, Jane (Vanessa Redgrave), who is desperate to obtain a

roll of film that he snapped of her apparent meeting with a lover. She goes so

far as to come home with him and partially undress. Her flirtations appear to

bear fruit – he gives her what she thinks she wants. In reality, however, it’s

an empty film roll. Curious about her desperation, he develops the film and,

after blowing up part of the image, discovers what he believes to be evidence

that she was involved in a murder. Antonioni never provides a clear-cut answer

as to whether someone was killed (there is a body, but the death could have

been by natural causes) or whether Thomas, caught up in the thrill of the

discovery, adds 2+2 to get 5. By the end of the film, Jane has vanished, the

negatives and photos have been stolen, the body in the park has been removed,

and Thomas slips back into the existence of ennui that defined him prior to

being temporarily jolted to life. No questions are answered and we perhaps don’t

realize until “The End” that the movie was never really about a murder in the

first place.

Thomas’ life seemingly consists of two components: work and

partying. He does both in a mechanical fashion that shows how detached he has

become from his everyday existence. One day while at a park, he has an odd

encounter with a woman, Jane (Vanessa Redgrave), who is desperate to obtain a

roll of film that he snapped of her apparent meeting with a lover. She goes so

far as to come home with him and partially undress. Her flirtations appear to

bear fruit – he gives her what she thinks she wants. In reality, however, it’s

an empty film roll. Curious about her desperation, he develops the film and,

after blowing up part of the image, discovers what he believes to be evidence

that she was involved in a murder. Antonioni never provides a clear-cut answer

as to whether someone was killed (there is a body, but the death could have

been by natural causes) or whether Thomas, caught up in the thrill of the

discovery, adds 2+2 to get 5. By the end of the film, Jane has vanished, the

negatives and photos have been stolen, the body in the park has been removed,

and Thomas slips back into the existence of ennui that defined him prior to

being temporarily jolted to life. No questions are answered and we perhaps don’t

realize until “The End” that the movie was never really about a murder in the

first place.

Blow-Up was released in 1966 by MGM. It was the first

movie rejected by the Production Code to obtain a wide release and the theaters

showing it didn’t care that it had not been given the seal of approval. Blow-Up

is often considered to be the last blow to the Hays Code. Once other films

noted that it was able to receive widespread distribution and make money, the

old system was swept away. Within years, the Motion Picture Association of

America introduced a new ratings system: “G”, “GP”, “R”, and “X” – a forerunner

of what we have today.

Blow-Up was released in 1966 by MGM. It was the first

movie rejected by the Production Code to obtain a wide release and the theaters

showing it didn’t care that it had not been given the seal of approval. Blow-Up

is often considered to be the last blow to the Hays Code. Once other films

noted that it was able to receive widespread distribution and make money, the

old system was swept away. Within years, the Motion Picture Association of

America introduced a new ratings system: “G”, “GP”, “R”, and “X” – a forerunner

of what we have today.

For audiences accustomed to the puritanical envelope created by the Hays Code, Blow-Up’s sex, nudity, and drug use were eye-openers. The nudity became a much-discussed subject although, by today’s standards, it’s less startling than the misogynistic attitude often displayed by Thomas, who might well be seen as an anti-hero by a modern audience. As an exhumation of the mores and attitudes of the Swinging Sixties, Blow-Up is excellent. As a thriller, however, its effectiveness is more complex and not always successful. Since the movie is regarded as seminal, no serious student of film history should ignore it and it’s by no means a difficult or unrewarding viewing experience – just be aware that the questions you expect to be answered are likely not the same ones that interested Antonioni.

Blow-Up (Italy/United Kingdom/United States, 1966)

Cast: David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave, Sarah Miles, John Castle, Jane Birkin, Gillian Hills, Peter Bowles, Verushka

Home Release Date: 2020-02-16

Screenplay: Michelangelo Antonioni and Tonino Guerra, base don the short story “Las babas del diablo” by Julio Cortazar

Cinematography: Carlo di Palma

Music: Herbert Hancock

U.S. Distributor: MGM

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Sexual Content, Nudity, Drugs)

Genre: Thriller

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- (There are no more better movies of David Hemmings)

- (There are no more worst movies of David Hemmings)

- (There are no more better movies of Sarah Miles)

- (There are no more worst movies of Sarah Miles)

Comments