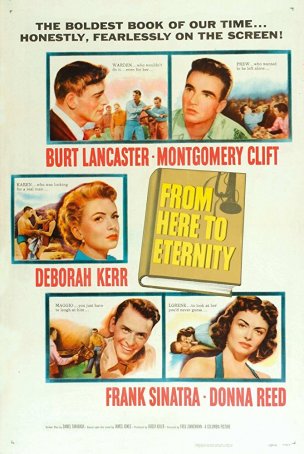

From Here to Eternity (United States, 1953)

June 30, 2018

The lasting image most people have of From Here to Eternity is of Sgt. Milton Warden (Burt Lancaster) embracing Karen Holmes (Deborah Kerr) on the beaches of Hawaii with the surf churning around them. This iconic moment, emblazoned in the minds of both those who have and haven’t seen the film, is more likely to be remembered than the story, the performances, or the eight Oscars taken home by the cast and crew, including Best Picture (not to mention another five nominations). Seen in retrospect, however, From Here to Eternity doesn’t look as polished as it did at its 1954 coronation. Although entertaining throughout and occasionally moving, the film is less an epic drama than an historically-based soap opera.

The production, based on the novel by James Jones, looked

back in time a dozen years to Hawaii before the Japanese sneak attack. An

expose of life in the army in the pre-state territory just prior to the

outbreak of hostilities, From Here to

Eternity focuses on the lives and loves of three soldiers: the stolid,

reliable Warden, the hard-headed, hard-drinking Prewitt (Montgomery Clift), and

the less serious (but no less stubborn) Maggio (Frank Sinatra). The ending

features images of the bombing and its immediate aftermath; this is included

not only as a way to conclude the narrative but to emphasize that the military

lifestyle as depicted during most of the film died as sudden and dramatic death

as the many soldiers on the sinking ships. This is not, however, a love story

disguised as a war movie – war isn’t much mentioned until the last quarter-hour

although the shadow of the historical event hangs over the entire 117-minute

running length.

The production, based on the novel by James Jones, looked

back in time a dozen years to Hawaii before the Japanese sneak attack. An

expose of life in the army in the pre-state territory just prior to the

outbreak of hostilities, From Here to

Eternity focuses on the lives and loves of three soldiers: the stolid,

reliable Warden, the hard-headed, hard-drinking Prewitt (Montgomery Clift), and

the less serious (but no less stubborn) Maggio (Frank Sinatra). The ending

features images of the bombing and its immediate aftermath; this is included

not only as a way to conclude the narrative but to emphasize that the military

lifestyle as depicted during most of the film died as sudden and dramatic death

as the many soldiers on the sinking ships. This is not, however, a love story

disguised as a war movie – war isn’t much mentioned until the last quarter-hour

although the shadow of the historical event hangs over the entire 117-minute

running length.

Although Lancaster received top billing, the character with the most screen time is Clift’s Prewitt. Newly transferred to a rifle company on Oahu, Prewitt arrives with baggage – he is a top bugler and was once a promising middleweight boxer. However, despite a plea from his new commander, Captain Dana Holmes (Philip Ober), to join the regimental boxing team, Prewitt remains firm in his resolution not to return to the sport. This earns him the ire of several others, although he is reunited with his old friend Maggio and forms a bond of mutual respect with his sergeant, Warden. Pressure, in the form of hazing, mounts on Prewitt to relent but he digs in his heels. One night, while at a social club, he meets an attractive “hostess” named Lorene (Donna Reed). The two fall in love but find it difficult to arrange time together. He doesn’t get many furloughs and she is part of Hawaii’s busy night scene.

Meanwhile, Warden has romantic issues of his own. He becomes involved with Karen Holmes, the neglected wife of his captain. She has a reputation for bedding and discarding men and this makes him wary but when she opens up to him about the reason for her promiscuity, he understands. This results in the kiss on the beach and subsequent conversations about commitment and the difficulty of their situation with her being married to his commanding officer.

Finally, the least significant of the film’s narrative

threads involves the gregarious Maggio, who is liked by nearly everyone except

Sgt. Judson (Ernest Borgnine), who takes offense at being called “Fatso.” Their

mutual disdain, fueled by Maggio’s tendency to drink too much, boils over in a

quarrel where blood is almost spilled. Although the situation is defused by

Warden’s intervention, Judson, whose dominion is the stockade, warns Maggio

that he will be waiting for him. Sure enough, Maggio goes AWOL and, after being

caught and subsequently court-martialed, he comes under Judson’s power.

Finally, the least significant of the film’s narrative

threads involves the gregarious Maggio, who is liked by nearly everyone except

Sgt. Judson (Ernest Borgnine), who takes offense at being called “Fatso.” Their

mutual disdain, fueled by Maggio’s tendency to drink too much, boils over in a

quarrel where blood is almost spilled. Although the situation is defused by

Warden’s intervention, Judson, whose dominion is the stockade, warns Maggio

that he will be waiting for him. Sure enough, Maggio goes AWOL and, after being

caught and subsequently court-martialed, he comes under Judson’s power.

From Here to Eternity’s director, Fred Zinnermann, came to the project during the most fruitful period of his 50-year career. Between 1948 and 1953, Zinnermann made three highly-regarded films for which he personally was Oscar-nominated (The Search and High Noon were the other two). From Here to Eternity earned him his first of two wins (the other was for 1967’s A Man for All Seasons which, like From Here to Eternity, also won Best Picture). Zinnermann’s fingerprints are all over From Here to Eternity. The horizontal beach cinch was his idea – as written, it was standing up. He also fought for (and won) the battle to shoot in black-and-white using the 1.33:1 aspect ratio (rather than one of the widescreen options that were coming into vogue). Zinnermann fought with Columbia’s head Harry Cohn over the casting of Montgomery Clift – the director threatened to quit if his preferred actor wasn’t hired.

Speaking of Clift, From Here to Eternity represented a career peak for him. The intense actor, whose popularity plateaued during the late 1940s and early 1950s, was referred in some circles as being only one of two performers who was both good-looking and talented. (The other was Marlon Brando.) Clift was nominated three times for Best Actor – also for 1951’s A Place in the Sun and 1948’s The Search (working with Zinnemann). It is widely suspected that he missed out on winning the Oscar in 1954 because he split the vote with fellow nominee Burt Lancaster, thereby opening the door for William Holden. By the time he made From Here to Eternity, Clift was already an alcoholic. In several scenes where Prewitt is drunk, Clift wasn’t acting.

For many of the other performers in From Here to Eternity, the production represented a departure from

type. Prior to this movie, Lancaster had primarily been seen as a lightweight.

His work here helped to re-direct his career trajectory in a serious direction.

Deborah Kerr, known for “prim and proper” roles, was given a chance to show off

a sexy, sensual side. Frank Sinatra, who won a Best Supporting Oscar, moved

away from the comedies and musicals that had previously been his

bread-and-butter. (At the time of his casting, his career was at a low ebb. His

work here helped re-establish his reputation.) Finally, girl-next-door Donna

Reed was cast against type as a prostitute/hostess. She is so convincing that

one immediately forgets the role for which she is best remembered – Mary in It’s a Wonderful Life.

For many of the other performers in From Here to Eternity, the production represented a departure from

type. Prior to this movie, Lancaster had primarily been seen as a lightweight.

His work here helped to re-direct his career trajectory in a serious direction.

Deborah Kerr, known for “prim and proper” roles, was given a chance to show off

a sexy, sensual side. Frank Sinatra, who won a Best Supporting Oscar, moved

away from the comedies and musicals that had previously been his

bread-and-butter. (At the time of his casting, his career was at a low ebb. His

work here helped re-establish his reputation.) Finally, girl-next-door Donna

Reed was cast against type as a prostitute/hostess. She is so convincing that

one immediately forgets the role for which she is best remembered – Mary in It’s a Wonderful Life.

Many in Hollywood thought James Jones’ novel was “unfilmable.” Numerous cuts and compromises had to be made to reduce the 800-page tome to a reasonable length. (Cohn demanded that Zinnemann turn in a final cut no longer than two hours.) The book’s profanity was eliminated and the prostitutes at a brothel were transformed into “hostesses” at a “social club” (although, reading between the lines, it’s clear what they really are).

Although From Here to Eternity’s portrayal of the military isn’t as negative and cynical as what developed during the post-Vietnam film period, the armed forces aren’t lionized. Petty aspects of the army’s culture are highlighted and, although the ending shows instances of heroism, the film also highlights darker elements, such as Captain Holmes’ selfishness and Sgt. Judson’s brutality. The film tells a compelling story with many of the elements that audiences find appealing. However, 65 years later, there’s little about From Here to Eternity to differentiate it from other well-made productions of its era.

From Here to Eternity (United States, 1953)

Cast: Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift, Deborah Kerr, Donna Reed, Frank Sinatra, Philip Ober, Ernest Borgnine, Jack Warden

Home Release Date: 2018-06-30

Screenplay: Daniel Taradash, based on the novel by James Jones

Cinematography: Burnett Guffrey

Music: Morris Stoloff, George Duning

U.S. Distributor: Columbia Pictures

- (There are no more better movies of Burt Lancaster)

- (There are no more worst movies of Burt Lancaster)

- (There are no more better movies of Montgomery Clift)

- (There are no more worst movies of Montgomery Clift)

- (There are no more better movies of Deborah Kerr)

- Casino Royale (1969)

- Black Narcissus (1947)

- (There are no more worst movies of Deborah Kerr)

Comments