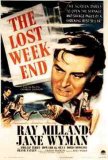

Lost Weekend, The (United States, 1945)

August 03, 2010

Billy Wilder, one of the titans of cinema during the 1940s and 1950s, won his first Best Director Oscar for 1945's The Lost Weekend (he would go on to win another for 1960's The Apartment). Over a span of 21 years beginning in 1940 and concluding in 1960, Wilder was nominated a staggering sixteen times in the writing and/or directing categories. By the time The Lost Weekend became a big winner at the 1946 celebration, capturing four of the seven citations for which it was eligible, Wilder was already among the Hollywood elite. The victories added luster to the filmmaker's burgeoning reputation as he entered the most fruitful era of his career.

The Lost Weekend is the perfect example of how shifting tastes and cultural values can alter the way a movie is seen. At the time of the film's release in 1945, there was much debate about whether alcoholism was a disease or a weakness of character, and there was no shortage of advocates for either position. (The AMA officially declared alcoholism an "illness" in 1956.) Today, the "disease theory" is widely accepted by both medical practitioners and lay people. Few people in 2010 believe that alcohol addiction is the result of a personality flaw. The change in thinking that largely ended the debate influences the perspective brought to The Lost Weekend by a potential viewer. Also, although the movie was viewed as hard-hitting and edgy in 1945, it has been superseded by motion pictures about alcoholism and drug addiction that are far tougher. Compared to something like Requiem for a Dream, The Lost Weekend appears tame and a little naïve. Nevertheless, it was seen as anything but that upon its release, when it became the first major motion picture to use a "pull no punches" approach in depicting how a life could be wasted by the compulsion to consume the contents of a bottle.

Before The Lost Weekend, the typical portrayal of a drunk was comedic in nature, with Chaplin's Little Tramp, who often imbibed too much, being a prime example. Drunkenness and comedy in movies have long been entwined. Hollywood, which has been awash in alcohol throughout its history, did not like to scrutinize this vice too closely. Thus, The Lost Weekend, in which there is no hint of humor, stands apart as an early attempt to dramatize the deleterious effects of alcohol abuse by providing a protagonist who is sympathetic but not loveable.

Ray Milland, who in 1945 was near the height of his popularity, plays Don Birnam, an aspiring writer whose desire to pen a novel has been derailed by his inability to give up drinking. His brother, Wick (Phillip Terry), and his girlfriend, Helen (Jane Wyman), have decided upon a course of tough love (what today might be considered an "intervention"). Wick plans to take Don to a place in upstate New York where he can have a long, quiet weekend under his brother's supervision. However, impelled by the desperation and cunning of a drunk needing a fix, Don slips his brother's leash and goes on a bender. Once the weekend is over, Don has lied and stolen, spent time in Bellevue, and is faced with a life-changing (or life-ending) decision.

The ending of The Lost Weekend is its weakest part, with a pollyanna outlook that neither fits nor is fully justified by what precedes it. After acknowledging that no alcoholic will seek help until he hits rock bottom, the movie constructs a series of artificial sequences that allow this to occur. Don's decision to stop drinking and embrace recovery is too quick and convenient, and is far more simplistic than what most alcoholics endure before and during their 12-step program. The falseness of the ending, however, is more than compensated for by an otherwise effective and accurate portrayal of how the need for alcohol can turn an upright citizen into a deceptive, craven, belligerent animal. In his quest for booze (and the money to procure it), Don does some despicable things; the only reason he survives the weekend without being arrested or beaten to a pulp is because so many people take pity on him.

Ultimately, in the time-honored tradition of motion pictures, love provides Don with the path to redemption. We are shown key elements of his three-year relationship with Helen, including their first meeting and an incident that leads him to fall off the wagon. She knows about his addiction and has decided to stay with him for better or worse, and she's there at the end when he needs her the most desperately. She's as good a girlfriend as one could hope for: pretty, sophisticated, smart, and devoted. One of the points of the movie is to illustrate that even with someone like her helping him, the lure of alcohol is too strong. And The Lost Weekend shows to a degree what anyone having attended an Al-Anon meeting knows: the friends and relatives of alcoholics often suffer as much as the victim.

When Wilder read the novel by Charles R. Jackson, he was certain it could form the basis for a powerful and ground-breaking motion picture. To that end, he lobbied Paramount to obtain the rights then went to work on the screenplay with frequent collaborator Charles Brackett. Once the script was completed, he encountered some difficulty finding an A-list actor to play the lead role, even though he promised a Best Actor win (a promise that was fulfilled) to each of the unwilling candidates. The studio was pressured by both alcohol producers and anti-drinking groups alike and concerns about a box office failure resulted in a limited release. Paramount needn't have worried. The critical response was rapturous and the popular reception was strong. By all accounts, The Lost Weekend was a success.

Ray Milland's career spanned 55 years and he was a major draw for about 15 years (from the mid-'30s until the early '50s), yet The Lost Weekend was not only his sole Best Actor win, but his only nomination. Despite some initial misgivings that it might hurt his career, Milland approached the role with full determination to get it right, and he delivers a compelling and convincing performance as a man who can't overcome his demon in a bottle. Milland is also widely regarded as having given the best Oscar acceptance speech ever: he ascended the stage, acknowledged the applause, then left without saying a word.

The Lost Weekend is Milland's picture; his co-stars are left with little to do. As Helen, Jane Wyman (the first Mrs. Ronald Reagan) fills the part of the supportive girlfriend, but this is hardly a showcase for the actress' talents. Those were better displayed in 1948's Johnny Belinda, for which she won a Best Actress award. Phillip Terry and Howard Da Silva, as Don's brother and a sympathetic bartender (respectively), have less to do. Both noted character actors, Terry and Da Silva fill their parts competently, but neither is memorable.

It's impossible to see The Lost Weekend through contemporary eyes in the same way viewers received it during its initial release. The movie remains a solid drama with a tremendous lead performance, but it no longer seems daring or shocking. Too much has happened between now and then, with society growing more sympathetic toward alcoholics and the stigma no longer as indelible. In some ways, The Lost Weekend is as interesting as a time capsule of what was considered "groundbreaking" 65 years ago as it is an enduring or timeless drama. Few who watch The Lost Weekend in 2010 will find that it offers insight not found elsewhere - a statement that was not true in 1945.

Lost Weekend, The (United States, 1945)

Cast: Ray Milland, Jane Wyman, Phillip Terry, Howard Da Silva, Doris Dowling

Screenplay: Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder, based on the novel by Charles R. Jackson

Cinematography: John F. Seitz

Music: Miklos Rozsa

U.S. Distributor: Paramount Pictures

- (There are no more better movies of Ray Milland)

- (There are no more worst movies of Ray Milland)

- (There are no more better movies of Jane Wyman)

- (There are no more worst movies of Jane Wyman)

- (There are no more better movies of Phillip Terry)

- (There are no more worst movies of Phillip Terry)

Comments