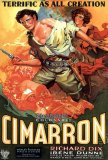

Cimarron (United States, 1931)

November 27, 2009

Cimarron, the recipient of the 1931 Best Picture Oscar, is an excellent study of how tastes have changed over the years. Critically lauded at the time of its release, Cimarron was beloved by most who saw it. Eight decades later, it is frequently cited on lists of the most undeserving Academy Award winners and is rightfully impugned for racist overtones and scattershot storytelling. Cimarron's Oscar gold (it won three awards and was nominated for four more) was indicative of the Academy's preference for big, splashy productions in the early days. This was the first instance of a Western - a popular genre at the time - winning.

Cimarron, which bears a closer resemblance to a disjointed soap opera than a traditional Western, covers a 40 year span in the fictional Oklahoma locale of Osage. In 1889, when the story begins, it's a crude town beginning to blossom as the United States expands west. In 1929, when the final act takes place on the eve of the Depression, it's a thriving metropolis whose expansion has been fueled by the oil found under the ground of the nearby Osage Indian Reservation. While the four decade scope allows for an appreciation of how settlements in the Old West boomed, the characters are given little opportunity to develop personalities beyond those defined by their core traits. It's tough to care much about the men and women populating Cimarron or their relationships. That makes for a dry and unrewarding experience of watching it as anything more than an historical artifact.

The film's opening segment concerns the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush - a Manifest Destiny-fueled event that allowed settlers to surge forward into the Unassigned Lands and stake their claim on a parcel of land. Cimarron's lead character, Yancey Cravat (Richard Dix), has arrived early from his current home in Wichita, Kansas and done his homework. He knows exactly where he wants to stake his claim and build his home. In the end, however, he is beaten to the site by the trickery of a prostitute named Dixie Lee (Estelle Taylor). He returns home without title to his dream land but with a burning desire to be part of the westward expansion. He, his wife, Sabra (Irene Dunne), and his young son emigrate to Osage, where he becomes a prominent citizen and the editor of the local newspaper, The Oklahoma Wigwam.

Yancey is a restless individual and, when the 1893 Cherokee Strip Land Rush is announced by President Cleveland, he is burning to participate. Leaving behind his family, which now includes a toddler daughter, Yancey disappears for five years. He doesn't return to Osage until he has completed a stint in army during the Spanish American war. Yancey stays home for the better part of a decade, using his newspaper to espouse liberal viewpoints and defend Indian rights until wanderlust strikes again. This time, when he departs, it appears to be for good. Over the years, the previously conservative Sabra is converted to many of Yancey's causes and she brings them with her to Washington when her run for Congress is successful.

In its views of minorities, which vary from condescending to insulting, Cimarron was deemed progressive for its time. Neither Native Americans nor Jews nor blacks fare well in a story that professes to address issues of equality and social reform. Stereotypes abound. The decision to give Isaiah, the black child who works as a servant to the Cravats, a heroic death does not repair the caricature he represents in life. Likewise, Jewish merchant Sol Levy is a synthesis of traits commonly attributed to Jews during the early 20th century, and only lip service is paid to the "royalty" of American Indian princess Ruby Big Elk. The filmmakers believed they were being fair and open-minded and, by the standards of the day, they were. Most viewers of Cimarron during its initial release would not have found anything racially demeaning about any of the portrayals. However, it's likely that most Native Americans, African Americans, and Jews watching this film today would feel insulted by at least some of what's on the screen. One argument for watching Cimarron (which could also be applied to the even more negatively-toned Birth of a Nation and the film "hidden" by Disney, Song of the South) is that it provides a window into a mindset that the historical record may not always accurately represent.

Despite positive critical response at the time of its opening, Cimarron was not financially successful. The high production cost was a contributing factor, with a budget of nearly $1.5 million. Recouping that in a Depression-era economy proved to be impossible, even though the film was packed with flourishes that were popular with movie audiences in the '30s (some of which have become dated over the years). With the exception of the opening land rush, which was re-created using 5000 extras and more than two-dozen cameramen and holds up as well as a similar sequence in 1992's Far and Away, little in Cimarron is technically noteworthy. This isn't a film that introduced new cinematic techniques to the world.

Cimarron might look good, but the story is poorly paced and uneven - herky-jerky melodrama that never achieves any narrative momentum. By jumping from era to era and occasionally bypassing significant events, the film never achieves cohesiveness and the characters feel less than fully formed. (This often happens when a movie attempts to cram an epic scope into a two hour slot.) There's also some obvious sermonizing. A segment is devoted to Yancey's courtroom defense of a prostitute; he blames her misdeeds on society and gives a long speech explaining how her moral fall is not her fault. The incident is so flamboyant that, viewed today, it's almost funny in a campy fashion (although I'm sure it came across as serious in the pre-FDR landscape of 1931).

The film's director, Wesley Ruggles, was a veteran of the silent era; this was his fourth sound endeavor. He would continue to make movies until his retirement in 1946. Ruggles was prolific if not artistically minded. In 1925, the peak year of his career, he helmed no fewer than 16 productions. He slowed in the talkie era, but still managed to crank out four films in 1935. Cimarron was his only Oscar nomination; he lost to Norman Taurog for Skippy.

The lead actor and actress, Richard Dix and Irene Dunne, were popular stars in their era. Over the years, Dunne's name has endured while Dix's has not. Dix was a significant figure in the early sound period; his voice was deep and commanding and perfectly suited to films that demanded a leading man who could sound as imposing as he looked. Dix was already an established actor by the time he played Yancey Cravat, but his work in Cimarron, coupled with his Best Actor Oscar nomination (the only one of his career), provided new opportunities. He continued to work until his death in the late 1940s but the passage of time thereafter has not been kind to his name. His performance in Cimarron is hammy and over-the-top, an approach more appropriate to silent films and the stage. Dunne, on the other hand, is well-remembered, due in part to five Academy Award nominations in a 20-plus year career (she never won). Cimarron was her second film and provided her first nomination. Her portrayal is low-key, which makes Sabra more believable than Yancey, although the clumsy writing does her no favors.

Cimarron was based on the novel by Edna Ferber. At the time, Ferber's books were much sought-after for screen adaptations. By 1940, Show Boat had already been adapted twice (a third version, in 1951, featured Dunne). The rights to Cimarron, which was published in 1929, cost RKO $125,000 - an astounding figure at the time. Aside from Show Boat, the best-known movie based on a Ferber novel is probably Giant, whose stature was assured by James Dean's death. Cimarron was re-made in 1960 and there are rumors that a new reworking of it is on Hollywood's radar for release sometime early in the next decade.

Among the early Oscar winners, Cimarron takes its place alongside those that are poorly remembered and rarely watched by modern audiences. It is not generally regarded as a classic and its mediocre reputation discourages all but the most devoted black-and-white film enthusiasts from seeking it out. According to IMDb's rating system, it has the lowest score of any Best Picture winner. There's nothing definitive about that, but it highlights how poorly the production has weathered the decades. Despite its flashy production design and big budget, it's shallow and unsatisfying and primarily interesting for what it says about the views of society when it was made.

Cimarron (United States, 1931)

Cast: Richard Dix, Irene Dunne, Estelle Taylor, Nance O'Neil, Rosco Ates, George E. Stone, Eugene Jackson

Screenplay: Howard Estabrook, based on the novel by Edna Ferber

Cinematography: Edward Cronjager

Music: Max Steiner

U.S. Distributor: RKO Pictures

- (There are no more better movies of Richard Dix)

- (There are no more worst movies of Richard Dix)

- (There are no more better movies of Irene Dunne)

- (There are no more worst movies of Irene Dunne)

- (There are no more better movies of Estelle Taylor)

- (There are no more worst movies of Estelle Taylor)

Comments