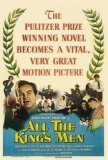

All the King's Men (United States, 1949)

November 29, 2010

It's a truism that many of the movies made during the '30s, '40s, and '50s have lost the impact they achieved upon their initial release. Changing times and cultural shifts have robbed them of their relevance, making them at times seem quaint and naïve. Something that might have been shocking near the dawn of the Cold War could be viewed with a blasé indifference in the 21st century. It's a different story altogether for All the King's Men, Robert Rossen's 1949 Oscar-winning adaptation of Robert Penn Warren's 1946 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. Not only has this movie stood the test of time, but its content is as uncomfortable and relevant today as it was the day the film premiered.

Those who pay close attention to the news, especially as presented on the 24-hour cable channels, might believe that politics have never been nastier and dirtier than they are today. Students of history know better. The only difference in 2010 is that every harsh word, lie, smear, and attempt at misinformation is recorded and played around the world. But the underlying mechanisms of how to win an election are not fundamentally different than they were 200 years ago, 100 years ago, or when the fictional lead character of All the King's Men embarked upon his meteoric political rise. If not for the black-and-white images and the occasionally "old fashioned" language, one might assume this movie was a recent attempt to graft today's political shenanigans on a Depression-era gubernatorial race.

When Willie Stark (Broderick Crawford) begins his political career, it's as a failed candidate challenging the hand-picked selection of the local Machine. Big-city newspaper writer Jack Burden (John Ireland) is sent into the sticks to write about the "only honest man running for office." Unlike so many losers, however, Stark doesn't go away. He runs for governor, designated as the man who can split the opposition's vote, but he learns one important lesson from his second defeat: what it takes to win. Four years later, breathing hellfire and brimstone, he goes on the attack. His message is music to the ears of the downtrodden - he will return power to the people and give a voice to the dumb. The people elect him to be fulfill his agenda. Star soon proves to be adept at playing the games of politics. Using a combination of bribery, intimidation, and graft, he is indomitable. Jack, after quitting his job at the paper, becomes Stark's right-hand (hatchet) man and sees everything up-close, including Stark's besmirching of the reputation of the honorable Judge Stanton (Raymond Greenleaf), his affair with Jack's intended, Anne (Joanne Dru), and his shameful treatment of his own son, Tom (John Derek). Once a great believer in Stark's message of change, Jack becomes disillusioned, recognizing that, like power, politics corrupts.

To say that All the King's Men struck a nerve during its original release is to understate matters, but the universality of themes represented in the movie were recognizable even to viewers whose communities were far different from the quintessentially Southern milieu in which the narrative unfolds. Although events on-screen transpire during the '30s and the film was made during the '40s, All the King's Men needs no updating or translating to seem current in the 2010s. None of the dirty tricks or ploys are difficult to believe - we have lived through political scandals with darker overtones. Nevertheless, it's worth remembering that the era into which this movie was introduced was a more innocent one. It would not be until nearly a quarter-century after the release of All the King's Men, when Watergate brought down in ruins the remnants of Camelot, that America truly began to understand the timeless and pervasive nature of political corruption. Even the man with the best intentions and the purest ideals cannot fend off the compromises necessary to achieve even a part of his agenda. There's an age-old question about the end justifying the means, and that's what All the King's Men asks. It does not, nor can it, give a definitive answer.

Warren's novel was streamlined and condensed to make for a more straightforward screenplay. Although the movie retains the book's approach of employing Jack as the narrator, his story is curtailed to allow Stark to expand and fill the creases. A subplot involving Jack's parentage has been deleted. Writer/director Robert Rossum saw it as an unnecessary diversion from the narrative he was pursuing. Another significant change involves the besmirching of Stark's son, Tom. In the book, his indiscretion is to impregnate a girl out of wedlock. In the movie, there is no pregnancy but the girl dies in an automobile accident caused by Tom's drunk driving. In 1949, it was thought that a drunk driving accident would be more "palatable" than an unmarried pregnancy. The change proved fortuitous in the long-term. In 2010, a drunk driving death represents something more serious and politically damaging than a pregnancy outside of marriage. The stigma of the former has increased over the years; that of the latter has faded into obscurity.

All the King's Men, although featuring a fictional lead, is based in part on the real life exploits of Huey Long, who served as the governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932. Many aspects of Long's career (including the manner in which it ended) are similar to Stark's. In numerous published interviews, Warren acknowledged that aspects of the character are based on Long; however, All the King's Men was never intended as a biography - not even a fictionalized one. Indeed, the skyrocketing appeal of Stark, fueled by public dissatisfaction with the status quo and a desire to shake up the establishment, is a common occurrence and not confined to a maverick Louisiana politician.

In 2006, Schindler's List scribe Steven Zaillian directed a remake of All the King's Men. Zaillian's script, which acknowledged only the source novel and not the 1949 movie, suffers from a poor focus and an uncertain chronology (he elects to employ frequent flashbacks rather than a linear approach). One of the key flaws is that the 2006 version focuses primarily on the narrator, Jack Burden, who is a bland character. Rossen recognized that Stark is by far the more interesting and charismatic individual, so he establishes him at the screenplay's nexus. Although Zaillian's interpretation may technically be more faithful, Rossen's is the better adaptation. All of the star power attracted for the 2006 film (Sean Penn, Jude Law, Kate Winslet, Anthony Hopkins, etc.) could not prevent it from being a pale imitation of its forebear.

Two actors took home gold statuettes for their work in All the King's Men. The Best Actor winner, Broderick Crawford, reached the zenith of his motion picture career with this performance, which transitioned Stark from an obscure idealist into a secular preacher into the spider at the center of a toxic political web. Contrast this with Sean Penn's cartoonishly over-the-top portrayal in the 2006 edition. Crawford was never a popular Hollywood actor, in part because of typecasting, but he became a familiar face on television beginning in the late 1950s. The other Oscar winner was Mercedes McCambridge, whose role as the acid-tongued Sadie Burke, one of Stark's advisors, placed her in the Best Supporting Actress category. This was the first screen role of a long and prosperous career for McCambridge, although it was the only time she would win an Academy Award. Other key performers include John Ireland, whose interpretation of Jack is unfortunately static (but which nevertheless earned him a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination) and John Derek, whose main claim to fame would be off-screen: he married, in succession, Ursula Andress, Linda Evans, and Bo Derek (and photographed all of them in the nude for Playboy).

Although Robert Rossum's film won the big prize at the 1950 ceremony, he lost in both the Best Director and Best Screenplay categories. All the King's Men would be Rossum's most notable work for more than a decade; past associations with the Communist Party led to his being blacklisted in 1951. When he "named names" in 1953, he was again allowed to work in Hollywood, but not until 1961's The Hustler did he regain the critical and popular acclaim achieved for All the King's Men. Despite being Oscar nominated four times (twice for All the King's Men and twice for The Hustler), Rossum never won an Academy Award.

All the King's Men remains a member of the select community of early Oscar winners (pre-1960) to have not only achieved the honor in its day but to appear many years later to have been deserving of it. The continued relevance of the content is evident in Zaillian's decision to mount the 2006 remake. The failure of the star-studded recent interpretation casts no shadow over the success of its predecessor. The 1949 All the King's Men, with its spare script, solid acting, and uncompromising direction, remains both a compelling drama and a cautionary tale - one whose message has not been heeded in the more than half-century since Rossum gave images to Warren's clarion call. The film has lost none of its power and is a more worthy choice for viewing by a modern audience than the 2006 misfire.

All the King's Men (United States, 1949)

Cast: Broderick Crawford, John Ireland, Joanne Dru, John Derek, Marcedes McCambridge, Shepperd Strudwick, Raymond Greenleaf

Screenplay: Robert Rossen, based on the novel by Robert Penn Warren

Cinematography: Burnett Guffey

Music: Louis Greenberg

U.S. Distributor: Columbia Pictures

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Violence)

Genre: DRAMA

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- (There are no more better movies of Broderick Crawford)

- (There are no more worst movies of Broderick Crawford)

- (There are no more better movies of John Ireland)

- (There are no more worst movies of John Ireland)

- (There are no more better movies of Joanne Dru)

- (There are no more worst movies of Joanne Dru)

Comments