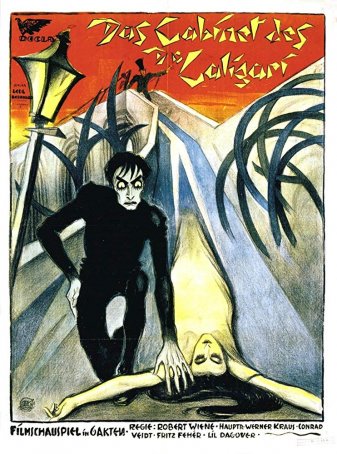

Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The (Germany, 1920)

April 12, 2019

Spoilers! (Is that relevant for a film that’s 100 years old??)

In no way does any aspect of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari resemble what we today would identify as “film.” With its bizarre set design, over-the-top acting, and operatic style, Robert Weine’s movie reflects a break with the norms of early cinema, which often tried to reflect reality rather than subvert it. Weine’s use of German Expressionism in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari sets it aside as one of the few movies to embrace the approach in every production aspect. Although only a few such films were produced in Weimar Germany, certain elements became major influences not only in future German productions but in Hollywood’s subsequent monster movie craze and, even farther down the line, in film noir.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a story about madness and murder told from the perspective of an insane man. Although we think we know where the narrative is leading, the final scene upends everything. We are left unsure how much (if anything) of what we have seen is real and whether the narrator, the title character, or both are lunatics. Once one understands the role of the so-called “unreliable narrator” in the telling of the tale, the outlandish setting, with its stark angles and weird backdrops, feels oddly appropriate. The movie opens a portal to that part of a twisted, fractured fairy tale where nightmare has replaced fantasy.

If not for the framing story, one could distill The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari into an

almost conventional murder mystery with anti-authority overtones. The movie

opens with a young man, Francis (Friedrich Feher), sitting on a park bench next

to an older gentleman (Hans Lanser-Ludolff). Francis offers to tell his

companion a story about things he and his wife experienced a number of years

ago. Thus begins a flashback that consumes the next 65 minutes of film.

If not for the framing story, one could distill The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari into an

almost conventional murder mystery with anti-authority overtones. The movie

opens with a young man, Francis (Friedrich Feher), sitting on a park bench next

to an older gentleman (Hans Lanser-Ludolff). Francis offers to tell his

companion a story about things he and his wife experienced a number of years

ago. Thus begins a flashback that consumes the next 65 minutes of film.

The action transpires in the (fictional) town of Holstenwall, which is represented as a cloth background painting of spiraling streets with skewed buildings. It’s fair-time and people have come from far and wide to see the acts and sideshows. Two residents, Francis and his friend Alan (Hans Heinrich von Twardowski), both vying for the affections of the lovely but aloof Jane (Lil Dagover), come to see what the fair has to offer. One of its attractions is the tent of Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss), who offers an audience with his somnambulant, Cesare (future international star Conrad Veidt, whose credits would include Casablanca). According to Dr. Caligari, Cesare has slept for all 23 years he has been alive and, upon wakening, he will be able to answer any question. Perhaps unwisely, Alan asks “How long will I live?” Cesare’s response, “Until dawn,” proves prophetic. Alan is found murdered in his bed, the second killing in as many days.

Francis vows to track down the killer and the trail leads

him to Dr. Caligari and Cesare. However, before any action can be taken against

the showman, an unrelated suspect is captured and an attempted murder of Jane

turns into an abduction. Cesare is found to be responsible; he dies in a fall.

Dr. Caligari escapes but Francis follows him to an insane asylum where he is

not one of the inmates (as Francis initially assumes) but the director. While

Dr. Caligari is sleeping, Francis discovers his diary and learns his plan (and

its motivation): learn whether a normal person, while asleep, can do things he

would never consider when awake. Discovered, Dr. Caligari is taken into custody

and becomes a prisoner in his own asylum.

Or does he?

Francis vows to track down the killer and the trail leads

him to Dr. Caligari and Cesare. However, before any action can be taken against

the showman, an unrelated suspect is captured and an attempted murder of Jane

turns into an abduction. Cesare is found to be responsible; he dies in a fall.

Dr. Caligari escapes but Francis follows him to an insane asylum where he is

not one of the inmates (as Francis initially assumes) but the director. While

Dr. Caligari is sleeping, Francis discovers his diary and learns his plan (and

its motivation): learn whether a normal person, while asleep, can do things he

would never consider when awake. Discovered, Dr. Caligari is taken into custody

and becomes a prisoner in his own asylum.

Or does he?

The movie closes with an epilogue set in the same “present” as the prologue. Francis has brought the old man from the park to the asylum to see things for himself. It becomes apparent that Francis, Jane, and a (very much alive) Cesare are all inmates. Dr. Caligari (not his real name) is the director. But we are left with a continuing sense of disquiet about whether this is the “truth” because, even in the supposed world of reality, the weird expressionist backdrops remain and the sense of claustrophobic madness continues. Could it be that there are many levels of insanity and we have not yet emerged from the labyrinth?

Although it’s fun to ponder the onion-like layers of the story, the modern viewer’s real interest in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is in observing how it looks and what it has contributed to the next 100 years of cinema. This strange, spooky production is endlessly fascinating to watch because of its extreme artificiality not in spite of it. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, with its real shadows and false ones (painted directly onto the sets), is a masterpiece of visual trickery. Its influences on movies like Nosferatu, Metropolis, M, Dracula, and Frankenstein are evident, but the tendrils reach farther to the likes of The Third Man and nearly every true noir production of the 1940s and 1950s. Even a seemingly unlikely candidate as Terry Gilliam’s Brazil can claim a kinship.

Director Robert Wiene imprinted his style on the film in several

notable ways. The movie is never truly black-and-white; it is tinted using

various colors (usually blue or orange) to represent the times of day and/or to

enhance emotions. Wiene exhibits a fondness for irises and often opens and

closes scenes with them. (An “iris” being the shrinking of the frame to a small

circle, like the contraction of a pupil when light is shone on it.) He also

uses them for emphasis. Although Wiene doesn’t do anything showy with the

camera, he occasionally uses jarring close-ups to shock the viewer. That may

have worked in 1920. Today, however, it comes across as amateurish. Despite a

career that spanned the entire silent era, Wiene is known primarily for two

films: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

and The Hands of Orlac, which he made

four years later.

Director Robert Wiene imprinted his style on the film in several

notable ways. The movie is never truly black-and-white; it is tinted using

various colors (usually blue or orange) to represent the times of day and/or to

enhance emotions. Wiene exhibits a fondness for irises and often opens and

closes scenes with them. (An “iris” being the shrinking of the frame to a small

circle, like the contraction of a pupil when light is shone on it.) He also

uses them for emphasis. Although Wiene doesn’t do anything showy with the

camera, he occasionally uses jarring close-ups to shock the viewer. That may

have worked in 1920. Today, however, it comes across as amateurish. Despite a

career that spanned the entire silent era, Wiene is known primarily for two

films: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

and The Hands of Orlac, which he made

four years later.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari contains its share of images that have become embedded in the annals of film history. At least three (and there may be more) come to mind. The first is a close-up of Cesare’s face as he his awakened from his slumber: wide, vivid eyes and jerky, terrified facial twitches. The second uses exaggerated shadows to depict Alan’s murder. The third is when Cesare abducts Jane, clad in a nightgown of purest white, and spirits her away like a monster carrying his prize. The movie is replete with moments like these. They cling to the memory with surprising tenacity; it’s possible to clearly remember The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari without recalling a single plot detail.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is universally recognized as an extreme example of German Expressionism in cinema – an approach that externalizes emotions and relies on a heavily theatrical acting style to achieve that aim. By today's standards, the performances, with their overdone gesticulations and exaggerated movements, are almost comically over-the-top; however, seen in context, there’s nothing unexpected about the emoting of Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, Friedrich Feher, Lil Dagover, or any of their co-stars.

As is true of all “silent” films, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was never intended to be watched in

silence. When it played in theaters, it was accompanied by either live

orchestras (in large theaters) or recorded accompaniments (in smaller ones).

Over the years, a number of companion pieces have been composed to play during

the film. It’s fascinating to note how the choice of music can subtly shape the

overall experience. The one available on the Kino DVD is effective. For an

interesting contrast, turn down the volume and experience how differently the

movie plays. Although there’s no spoken dialogue in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, complete silence is by no means the

ideal way in which to watch it.

As is true of all “silent” films, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was never intended to be watched in

silence. When it played in theaters, it was accompanied by either live

orchestras (in large theaters) or recorded accompaniments (in smaller ones).

Over the years, a number of companion pieces have been composed to play during

the film. It’s fascinating to note how the choice of music can subtly shape the

overall experience. The one available on the Kino DVD is effective. For an

interesting contrast, turn down the volume and experience how differently the

movie plays. Although there’s no spoken dialogue in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, complete silence is by no means the

ideal way in which to watch it.

In his retrospective review, Roger Ebert wrote: “A case can be made that Caligari was the first true horror film… In this world, unspeakable horror becomes possible.” Although the film was perceived more as a thriller at the time of its release, later viewers, filmmakers, and critics have come to see it as a template for films of dark psychological transgression. The decision to use the “unreliable narrator” was much discussed in contemporaneous reviews. Over the years, the device has become overused and so no longer surprises viewers, but it’s necessary to consider how shocking this would have been at the time. Indeed, there were passionate arguments about whether Wiene undermined or enhanced the movie’s themes by using the framing story. Some, like the celebrated director Fritz Lang, applauded it. Others, like the movie’s co-writer, Hans Janowitz (who claims he had no hand in scripting the prologue or epilogue), viewed it as a betrayal.

As with all examples of early cinema, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is worth seeing as much (if not more) for its historical value than simply as a visual interpretation of a story. The film’s imaginative approach offers an opportunity to explore the early roots of styles that were to become mainstream in Hollywood in the years and decades to follow.

Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The (Germany, 1920)

Cast: Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, Friedrich Feher, Lil Dagover, Hans Heinrich von Twardowski, Rudolf Lettinger, Hans Lanser-Ludolff

Home Release Date: 2019-04-12

Screenplay: Hans Janowitz, Carl Mayer

Cinematography: Willy Hameister

Music: Guiseppe Becce

U.S. Distributor: Goldwyn Distributing Company

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR"

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Subtitles: Silent Film

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- (There are no more better movies of Werner Krauss)

- (There are no more worst movies of Werner Krauss)

- Casablanca (1943)

- (There are no more better movies of Conrad Veidt)

- (There are no more worst movies of Conrad Veidt)

- (There are no more better movies of Friedrich Feher)

- (There are no more worst movies of Friedrich Feher)

Comments