Once Upon a Time, Cinema (Iran, 1992)

July 06, 2018

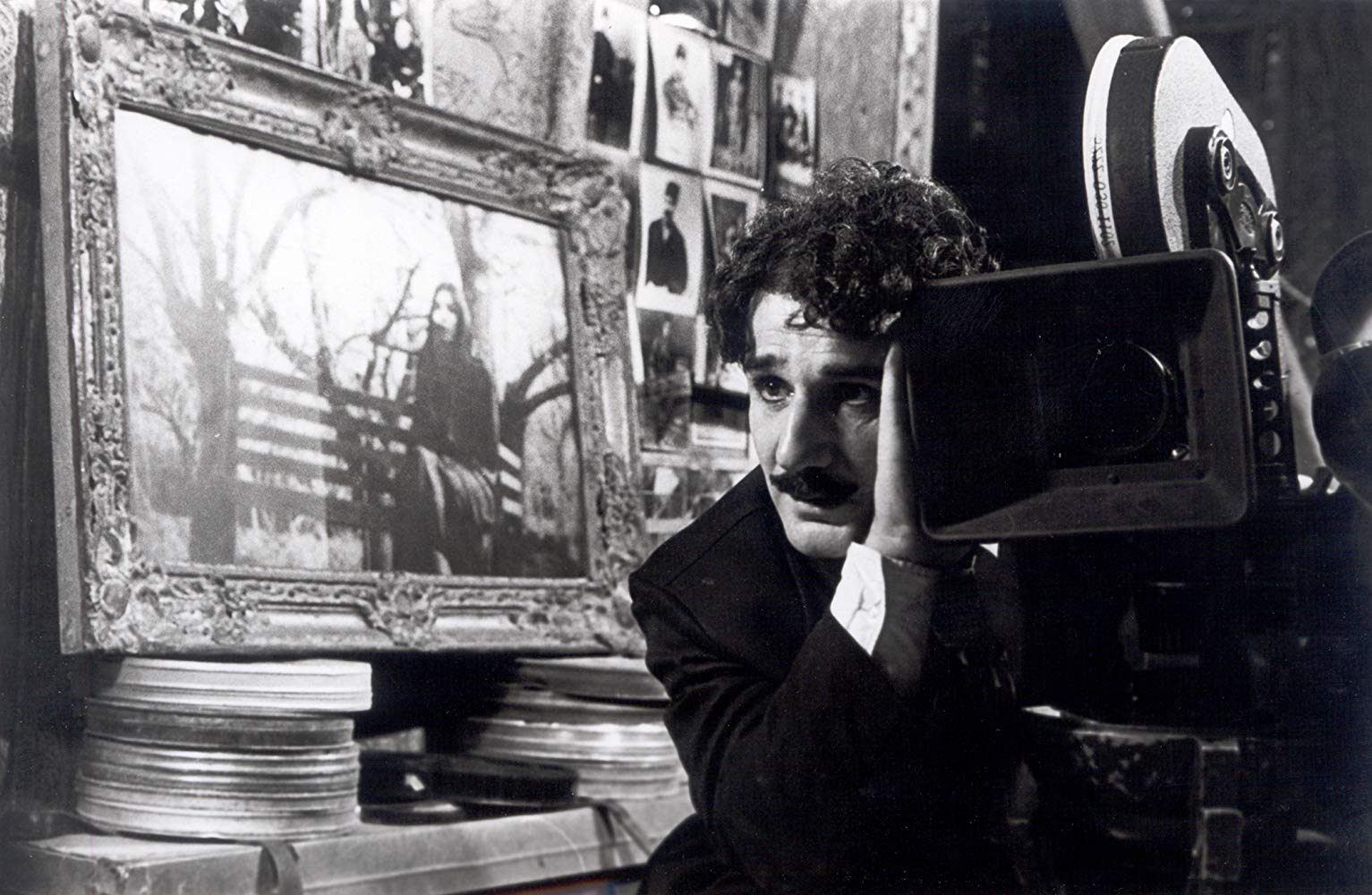

If you were to begin watching Once Upon a Time, Cinema with no knowledge of what you were seeing, you might initially mistake it for a lost silent film made during the 1910s or 1920s. In terms of style, approach, and technique, it’s a nearly perfect replica. The shots are sometimes inexpertly blocked. The cinematography is in grainy black and white. The editing is cursory with close-ups sometimes awkwardly intercut with medium-range shots. The special effects are laughable (at least by modern standards). Before too long, however, you’ll recognize the movie isn’t silent. There’s some dialogue. Not a lot, to be sure, but enough to catapult the era to post-Jazz Singer, maybe early 1930s. In fact, however, Once Upon a Time, Cinema was lensed in 1992.

The product of Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Once Upon a Time, Cinema, is an indulgence and a Valentine to movies. It has understandably been described as the “Iranian Cinema Paradiso” for the way it incorporates a love of cinematic history into its narrative. Makhmalbaf purportedly made this movie – something simple and uncontroversial – because his previous two films had been banned in Iran. Once Upon a Time, Cinema is largely apolitical, although it does illustrate the influential power of cinema and the baleful weight of censorship, but its style and setting deflect criticism (much as the allegorical aspects of science fiction can allow films of that genre to make bold statements without provoking outrage).

The story, which is decidedly not the film’s strong suit, begins in the early 20th century by

introducing us to The Cinematographer (Mehdi Hashemi), a pioneer post-Lumiere

filmmaker who wants to bring the glory of this new media to all of Iran. As The

Cinematographer travels the country with the eventual goal of being united with

someone named Atieh, his fame grows. In a surreal moment, he and his equipment

(a so-called “cinematographe”, a machine capable of recording, developing, and

projecting) are transported back through time to the reign of the current

Shah’s father (Ezzatolah Entezami) some 30 or 40 years earlier. In this time

before moving pictures were invented, the cinematographe is perceived as a

magical device and The Cinematographer as a kind of sorcerer.

The story, which is decidedly not the film’s strong suit, begins in the early 20th century by

introducing us to The Cinematographer (Mehdi Hashemi), a pioneer post-Lumiere

filmmaker who wants to bring the glory of this new media to all of Iran. As The

Cinematographer travels the country with the eventual goal of being united with

someone named Atieh, his fame grows. In a surreal moment, he and his equipment

(a so-called “cinematographe”, a machine capable of recording, developing, and

projecting) are transported back through time to the reign of the current

Shah’s father (Ezzatolah Entezami) some 30 or 40 years earlier. In this time

before moving pictures were invented, the cinematographe is perceived as a

magical device and The Cinematographer as a kind of sorcerer.

This Shah is entranced by The Cinematographer’s films, especially one called Lor Girl, a 1932 melodrama. He falls in love with the heroine, Golnar, who emerges from the film-world to the real-world by the same kind of magic that allowed The Cinematographer to travel through time. This translation occurs later with another movie, in which the hero of that production, a vigilante, exits the screen to engage the Shah in conversation. Eventually, in a last-ditch attempt to win Golnar’s love, the Shah asks The Cinematographer for acting lessons. These prove to be disastrous, as the Shah takes method acting to an extreme and believes himself to be a cow. Horrified by this development, the Shah’s underlings arrest The Cinematographer and prepare to execute him.

Once Upon a Time,

Cinema is less an example of storytelling than an exploration of filmmaking

as an avenue for experimentation and nostalgia. Although aspects of the way

Makhmalbaf presents the tale have a universality to them, the movie will have

greater meaning to those who are familiar with the referenced Iranian films.

Several of them, including Lor Girl

and the landmark 1969 noir drama/thriller Gheysar, are given substantial screen time and, as in Woody Allen’s Purple

Rose of Cairo, characters emerge from the movie world to interact with

those in the real world. (There’s also a scene in which a person from the real

world enters a movie.) Like Cinema Paradiso, the movie ends with a (full-color)

montage of clips from famous Iranian films intended to evoke a powerful

sense of nostalgia – something I’m sure will be accomplished for those familiar

with the movies. There’s also an obvious homage to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 during the closing sequence which,

although oddly placed, is as intriguing as it is unexpected.

Once Upon a Time,

Cinema is less an example of storytelling than an exploration of filmmaking

as an avenue for experimentation and nostalgia. Although aspects of the way

Makhmalbaf presents the tale have a universality to them, the movie will have

greater meaning to those who are familiar with the referenced Iranian films.

Several of them, including Lor Girl

and the landmark 1969 noir drama/thriller Gheysar, are given substantial screen time and, as in Woody Allen’s Purple

Rose of Cairo, characters emerge from the movie world to interact with

those in the real world. (There’s also a scene in which a person from the real

world enters a movie.) Like Cinema Paradiso, the movie ends with a (full-color)

montage of clips from famous Iranian films intended to evoke a powerful

sense of nostalgia – something I’m sure will be accomplished for those familiar

with the movies. There’s also an obvious homage to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 during the closing sequence which,

although oddly placed, is as intriguing as it is unexpected.

In keeping with the callbacks to the early days of moving pictures, The Cinematographer is intentionally represented as a near-lookalike of Chaplin’s Little Tramp. Everything, from his appearance (complete with fake mustache) to his movement and attitude, is reminiscent of one of the most memorable characters from the early days of moviedom. Indeed, Chaplin’s influence can be felt throughout large portions of the film, including a farcical chase scene.

For those with little-to-no experience with Iranian films, Once Upon a Time, Cinema is best viewed as an experiment in recreating early movies and intercutting existing footage with new re-creations. Those are mostly done seamlessly (with the exception of the scene in which the Shah and Gheysar converse). Love of cinema infuses every frame and the care taken to effectively reproduce early 20th century techniques is unquestionable. An offbeat and strangely engaging motion picture, Once Upon a Time, Cinema is worth a look for those with an interest in the history of Iranian cinema or for those who simply want to experience something off the beaten path.

Once Upon a Time, Cinema (Iran, 1992)

Cast: Mehdi Hashemi, Ezzatolah Entezami, Akbar Abdi

Home Release Date: 2018-07-06

Screenplay: Mohsen Makhmalbaf

Cinematography: Nemat Haghighi, Faraj Heidari

Music: Madjid Entezami

U.S. Distributor:

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR"

Genre: Fantasy/Drama

Subtitles: In Persian with subtitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- (There are no more better movies of Mehdi Hashemi)

- (There are no more worst movies of Mehdi Hashemi)

- (There are no more better movies of Ezzatolah Entezami)

- (There are no more worst movies of Ezzatolah Entezami)

- (There are no more better movies of Akbar Abdi)

- (There are no more worst movies of Akbar Abdi)

Comments