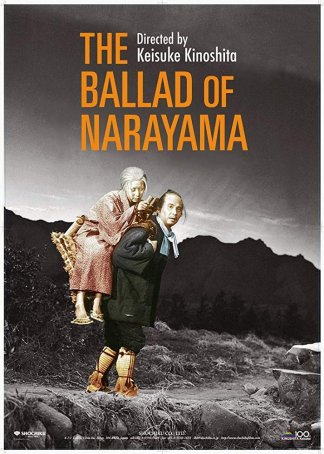

Ballad of Narayama, The (Japan, 1958)

August 11, 2019

The Ballad of Narayama,

a 1958 Japanese film from director Keisuke Kinoshita, is revered in some

critical circles because of its extreme stylization – using the art of kabuki

theater to form a template for the exploration of Shichiro Fukazawa’s novel.

Roger Ebert, in one of his final reviews, awarded the film four stars, and he

was not alone in his praise for it. However, the reason why some critics laud

the production is why I don’t believe it works. Kabuki on film is a hard sell,

especially for a Western audience. (I am aware that there’s a cultural divide

involved here both in terms of the era when The

Ballad of Narayama was made and the tradition in which it exists.) Its

artifice creates a unique, theatrical aesthetic but that leeches away any

emotional connection with the characters. They are too obviously actors playing

parts – chess pieces being moved around by a filmmaker. We are aware of the

movie’s central tragedy on an intellectual level but it doesn’t touch us the way it should. As a result,

The Ballad of Narayama feels drawn-out,

like a film school short that has been stretched beyond its natural length.

The Ballad of Narayama

transpires in a remote Japanese village where food shortages have resulted

in a policy that, once someone turns 70, a close family member will carry them

up into the mountains to a place called “Narayama,” where they are left in the

open to die of exposure. There are rules associated with the activity – no talking

is allowed inside Narayama, no one must see the soon-to-be-dead person and

his/her caretaker depart, and the caretaker cannot look back once the deed is

done. Some embrace this more willingly than others, seeing it as a necessary

sacrifice and natural progression of life.

One such person is Orin (Kinuyo Tanaka) who, as she

approaches her 70th birthday, speaks with anticipation of “going to

Narayama.” Death holds no fear for her. Her family is divided. Her son,

Tatshuei (Teiji Takahashi), is unwilling to face his part in the journey (he

will be the one to carry her). Orin’s grandson, however, is looking forward to

her being gone, since it will leave more food for him and his growing brood.

Meanwhile, in the same village, an elderly man, Mata (Seiji Miyaguchi),

approaches his end with less calmness and nobility. He doesn’t want to die and,

in the end, his son has to tie him up in order to get him to make the trip.

One such person is Orin (Kinuyo Tanaka) who, as she

approaches her 70th birthday, speaks with anticipation of “going to

Narayama.” Death holds no fear for her. Her family is divided. Her son,

Tatshuei (Teiji Takahashi), is unwilling to face his part in the journey (he

will be the one to carry her). Orin’s grandson, however, is looking forward to

her being gone, since it will leave more food for him and his growing brood.

Meanwhile, in the same village, an elderly man, Mata (Seiji Miyaguchi),

approaches his end with less calmness and nobility. He doesn’t want to die and,

in the end, his son has to tie him up in order to get him to make the trip.

The film is presented almost like a puppet show with live

actors taking the place of marionettes. This is especially evident during the

film’s visually arresting final 15 minutes, when there is almost no dialogue.

In order to convey strong emotions (especially with Kinoshita electing not to

use close-ups), the actors (notably Teiji Takahashi, who plays the son) employ

exaggerated movements similar to what one sometimes sees in stage plays (an

affectation necessary to inform viewers in the “cheap seats”). This type of

overacting was common during the silent era and carried over into the early talkies

but it’s surprising to see it in a 1958 production and is another result of

steeping The Ballad of Narayama in

the kabuki tradition.

The style is an attempt by Kinoshita to present The Ballad of Narayama as a fable. While

most films strive for some degree of “reality” (at least within the universe

where they transpire), this one embraces its essential “surreality.” The

village is rendered on a soundstage (complete with a running brook) with

detailed matte paintings serving as backdrops. The Narayama location is

populated by black crows and the skeletal remains of those who have previously

arrived to do their duty. It’s a grim, foreboding place, especially once a thin

covering of snow blankets it. Kubuki trappings are everywhere, from the acting mannerisms

to the usage of a (singing) narrator to the unique musical score emphasizing

strings and percussion.

The style is an attempt by Kinoshita to present The Ballad of Narayama as a fable. While

most films strive for some degree of “reality” (at least within the universe

where they transpire), this one embraces its essential “surreality.” The

village is rendered on a soundstage (complete with a running brook) with

detailed matte paintings serving as backdrops. The Narayama location is

populated by black crows and the skeletal remains of those who have previously

arrived to do their duty. It’s a grim, foreboding place, especially once a thin

covering of snow blankets it. Kubuki trappings are everywhere, from the acting mannerisms

to the usage of a (singing) narrator to the unique musical score emphasizing

strings and percussion.

The film’s look and feel are so pervasive that it’s easy to

lose sight of the great underlying tragedy. Obasute (referenced in the film’s

brief epilogue) is a Japanese legend about the abandonment of the elderly.

Kinoshita seeks to flesh out how this might have worked and the impacts it

would have had on those in the village who know the aging individual. Watching The Ballad of Narayama, it’s possible to

catch glimpses of the story’s power, but the style keeps interfering with the

narrative’s progression. In 1983, Shohei Imamura orchestrated a remake that

abandoned the kabuki elements and told the story “straight” (as in the source

novel). It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

The film’s look and feel are so pervasive that it’s easy to

lose sight of the great underlying tragedy. Obasute (referenced in the film’s

brief epilogue) is a Japanese legend about the abandonment of the elderly.

Kinoshita seeks to flesh out how this might have worked and the impacts it

would have had on those in the village who know the aging individual. Watching The Ballad of Narayama, it’s possible to

catch glimpses of the story’s power, but the style keeps interfering with the

narrative’s progression. In 1983, Shohei Imamura orchestrated a remake that

abandoned the kabuki elements and told the story “straight” (as in the source

novel). It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

For a casual film-goer with no special interest in kabuki or Japanese customs, The Ballad of Narayama has little to offer beyond the uniqueness of its presentation. Those seeking to learn more about the history of Japanese cinema and the influences of stage drama on its development will find value in The Ballad of Narayama. It works on a purely intellectual level, however, and is more useful for study than conventional viewing.

Ballad of Narayama, The (Japan, 1958)

Cast: Kinuyo Tanaka, Teiji Takahashi, Yuko Mochizuki, Danko Ichikawa, Seiji Miyaguchi, Keiko Ogasawara Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Home Release Date: 2019-08-11

Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita, based on the novel by Shichiro Fukazawa

Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda

Music: Chuji Kinoshita, Matsunosuke Nozawa

U.S. Distributor: Films Around the World

- Sansho the Bailiff (1955)

- (There are no more better movies of Kinuyo Tanaka)

- (There are no more worst movies of Kinuyo Tanaka)

- (There are no more better movies of Teiji Takahashi)

- (There are no more worst movies of Teiji Takahashi)

- (There are no more better movies of Yuko Mochizuki)

- (There are no more worst movies of Yuko Mochizuki)

Comments