Boy and the Heron, The (Japan, 2023)

December 05, 2023

In 2013, at the time of the release of his eleventh feature film, The Wind Rises, legendary Japanese animated filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki announced his retirement. It wasn’t the first time he had done so and, as on previous occasions, it didn’t stick. By 2015, he was back to work again, this time on the short film “Boro the Caterpillar.” Before that project saw the light of day, Miyazaki had already begun storyboarding what would become his twelfth feature film, The Boy and the Heron. From inception to screen, it took seven years. Although COVID caused some delays, the length of the production time was primarily due to Miyazaki’s age. No longer able to work at the rapid clip he had enjoyed throughout his career, he set a less strenuous pace. The result is a worthy entry into the filmmaker’s library of classic titles.

The Boy and the Heron finds inspiration in other Miyazaki films, autobiographical details, and the fantasy/mythology veins in which he has previously worked. The Boy and the Heron addresses the wisdom that comes from maturation and the bond between a mother and son. The main character is a child, as is often the case in Miyazaki films, and the setting switches between WWII Japan and another world that bears a passing resemblance to our own but features talking animals, wizards and warlords, and magical pre-birth souls called “Warawara.” (Perhaps coincidentally, this element tracks a plot point from Pixar’s direct-to-Disney+ 2020 release, Soul.) For those who found The Wind Rises to be an atypical Miyazaki effort, this is more in keeping with what fans have come to expect from the master.

The film opens in a real-world setting. It’s 1943, well into

the second World War, and bombs are raining on Tokyo. Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki),

the 12-year-old protagonist, loses his mother in a hospital fire. His widowed

father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), a factory owner, marries his late wife’s

younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), and relocates to her countryside

estate. Also living there are seven wizened old maids who gossip and fuss about

their younger charges. Mahito finds himself the target of a pesky grey heron (Masaki

Suda), whose presence grows increasingly ominous. The boy’s explorations of the

nearby forest uncover a sealed tower with a mysterious past. Meanwhile, Mahito

is having trouble adjusting to his new school and, after a fight, he injures

himself and pretends the bloody wound on his head was caused by another

student. Now temporarily home from school, Mahito tries to develop a kinder

relationship with his “new mother,” who is bedridden with morning sickness from

her pregnancy. But the grey heron absorbs Mahito’s attention as he attempts to

ascertain its nature and purpose.

The film opens in a real-world setting. It’s 1943, well into

the second World War, and bombs are raining on Tokyo. Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki),

the 12-year-old protagonist, loses his mother in a hospital fire. His widowed

father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), a factory owner, marries his late wife’s

younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), and relocates to her countryside

estate. Also living there are seven wizened old maids who gossip and fuss about

their younger charges. Mahito finds himself the target of a pesky grey heron (Masaki

Suda), whose presence grows increasingly ominous. The boy’s explorations of the

nearby forest uncover a sealed tower with a mysterious past. Meanwhile, Mahito

is having trouble adjusting to his new school and, after a fight, he injures

himself and pretends the bloody wound on his head was caused by another

student. Now temporarily home from school, Mahito tries to develop a kinder

relationship with his “new mother,” who is bedridden with morning sickness from

her pregnancy. But the grey heron absorbs Mahito’s attention as he attempts to

ascertain its nature and purpose.

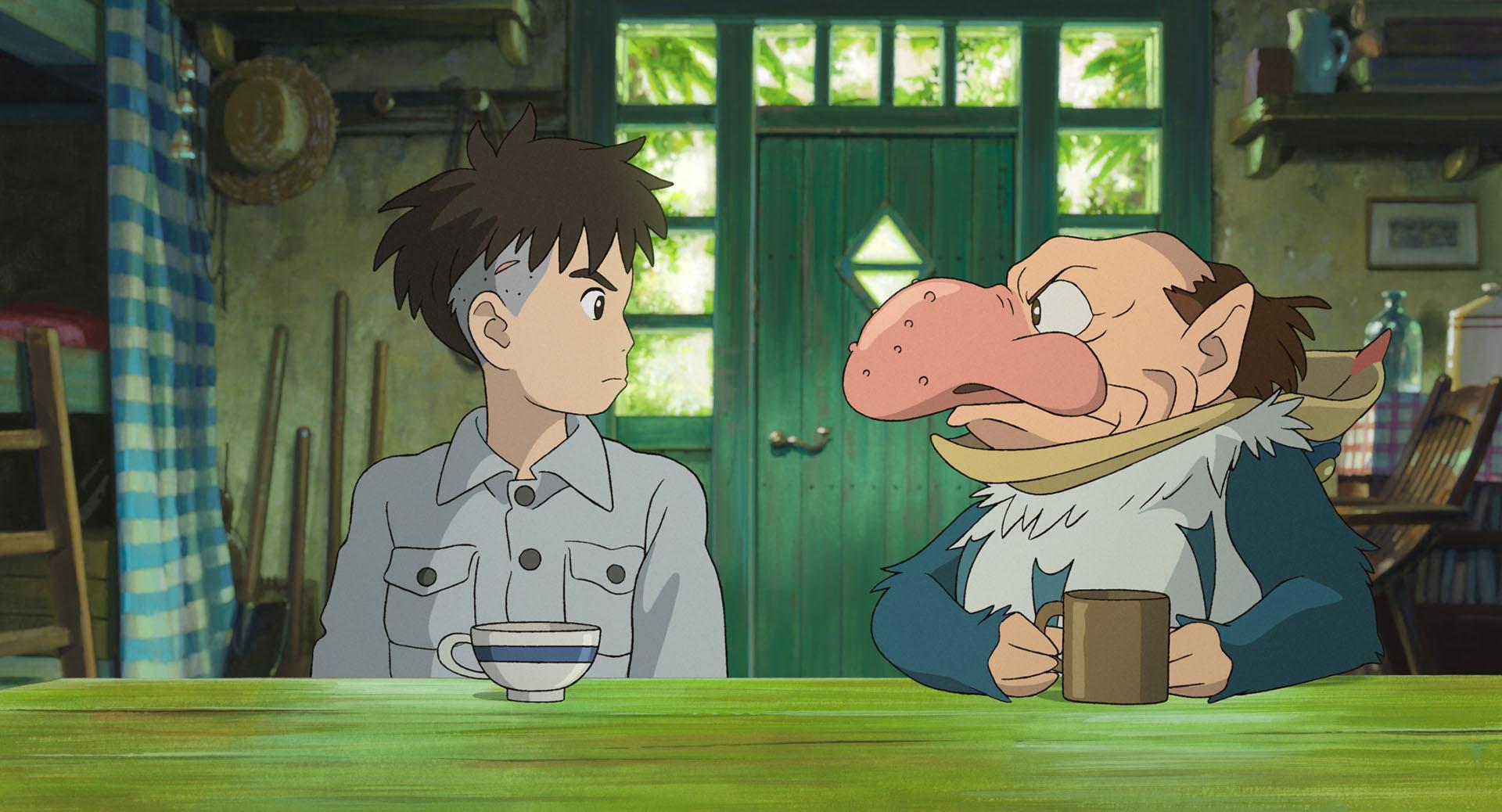

From this point, the movie goes “full Miyazaki,” which is to

say that it enters a fantastic, magical otherworld that is populated by odd

creatures, both familiar and monstrous. The grey heron turns out to be a

costume worn by a twisted old man. There’s a powerful magician and a stalwart,

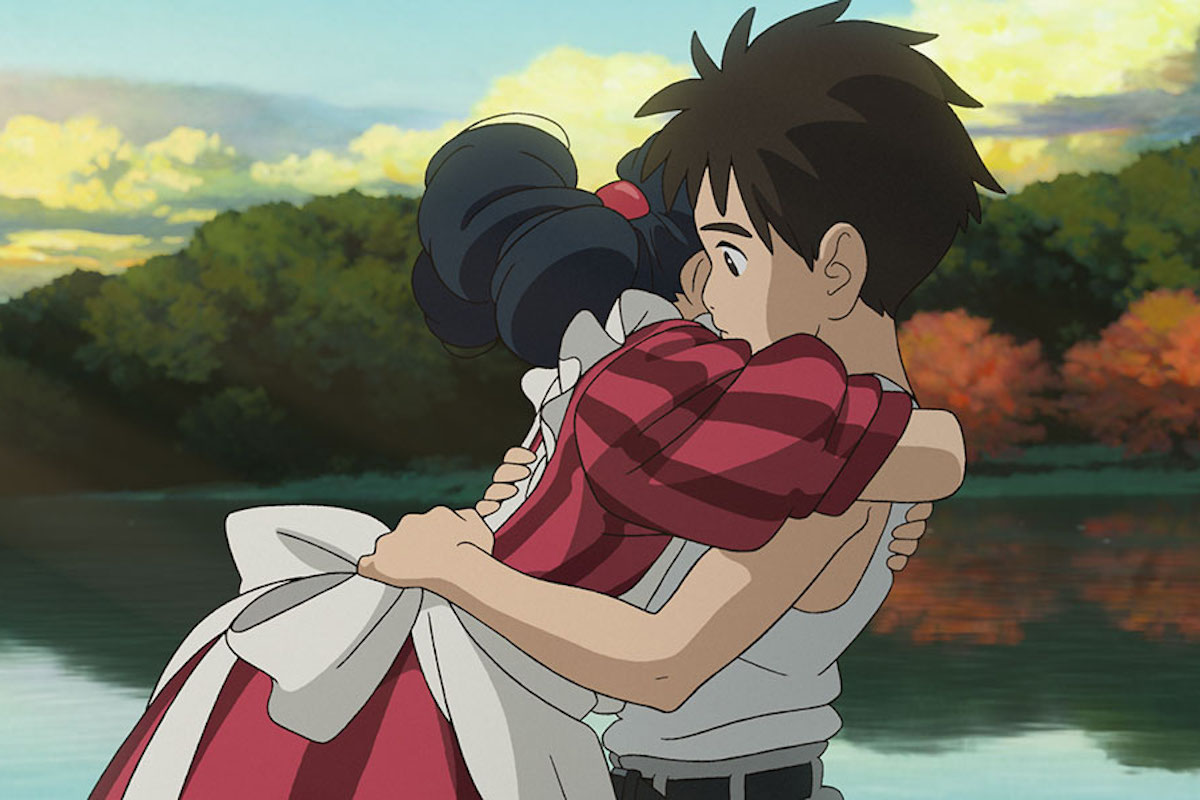

seafaring version of one of the old maids. Mahito, stubborn and grief-stricken

at the beginning, experiences his own version of a coming-of-age story as he

forms a bond with the grey heron and with a girl named Himi (Aimyon), who has a

surprising connection to Mahito’s past. The Boy and the Heron is about

Mahito’s healing from sorrow and growth as a person.

From this point, the movie goes “full Miyazaki,” which is to

say that it enters a fantastic, magical otherworld that is populated by odd

creatures, both familiar and monstrous. The grey heron turns out to be a

costume worn by a twisted old man. There’s a powerful magician and a stalwart,

seafaring version of one of the old maids. Mahito, stubborn and grief-stricken

at the beginning, experiences his own version of a coming-of-age story as he

forms a bond with the grey heron and with a girl named Himi (Aimyon), who has a

surprising connection to Mahito’s past. The Boy and the Heron is about

Mahito’s healing from sorrow and growth as a person.

The film’s animation is as good as anything Miyazaki has accomplished in his long, respected career. It remains hand-drawn, with computers used only in the distribution process (not the creative one). The watercolor backdrops are stunningly beautiful and, as has always been the case, the attention to detail is what differentiates this from the animated work of any of the world’s other top-notch studios. What other movie takes the time to show the protagonist changing into his pants in the morning before going outside? These are the little things that give characters life.

My preference has always been to watch Miyazaki’s films in

the original subtitled Japanese but GKIDS has spent a great deal of time and

effort creating an English-language dub that is a valid alternative for those who

prefer to avoid subtitles (or are too young to read them). The English version

of The Boy and the Heron has attracted a four-star voice cast; although

Mahito is played by the unknown Luca Padovan, other roles are provided by the

likes of Robert Pattinson (The Grey Heron), Gemma Chan (Natsuko), Christian

Bale (Shoichi), Mark Hamill, Florence Pugh, and Willem Dafoe.

My preference has always been to watch Miyazaki’s films in

the original subtitled Japanese but GKIDS has spent a great deal of time and

effort creating an English-language dub that is a valid alternative for those who

prefer to avoid subtitles (or are too young to read them). The English version

of The Boy and the Heron has attracted a four-star voice cast; although

Mahito is played by the unknown Luca Padovan, other roles are provided by the

likes of Robert Pattinson (The Grey Heron), Gemma Chan (Natsuko), Christian

Bale (Shoichi), Mark Hamill, Florence Pugh, and Willem Dafoe.

Miyazaki is not claiming The Boy and the Heron as his final film. He is apparently in the early stages of a new film and a close colleague has said he believes only death or disability will keep Miyazaki from working. Regardless of whether the future will bring another Miyazaki movie, The Boy and the Heron is a wonderful gift for everyone who expected The Wind Rises to be his swansong. It’s proof that, no matter how hard Disney, Pixar, Dreamworks, and others try, there’s only one animator who finds magic in every release.

Boy and the Heron, The (Japan, 2023)

Cast: Soma Santoki, Masaki Suda, Aimyon, Yoshino Kimura, Takuya Kimura, Shohei Hino, Ko Shibasaki

Screenplay: Hayao Miyazaki

Cinematography: Atsushi Okui

Music: Joe Hisaishi

U.S. Distributor: GKIDS

U.S. Release Date: 2023-12-08

MPAA Rating: "PG-13" (Violence)

Genre: Animated/Fantasy

Subtitles: In Japanese with subtitles (or dubbed)

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- (There are no more better movies of Soma Santoki)

- (There are no more worst movies of Soma Santoki)

- (There are no more better movies of Masaki Suda)

- (There are no more worst movies of Masaki Suda)

- (There are no more better movies of Aimyon)

- (There are no more worst movies of Aimyon)

Comments