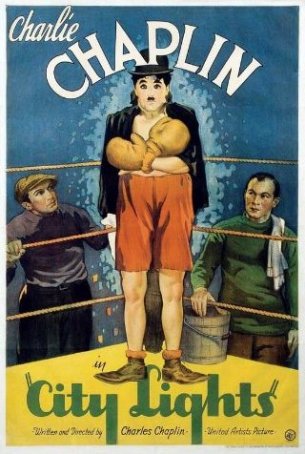

City Lights (United States, 1931)

In 1927, with much fanfare, The Jazz Singer was released. As every movie-lover knows, this otherwise unremarkable motion picture possessed one crucial asset: it was the first film to use recorded sound, and ushered in the "talkie" era. The transition from silent movies to those with sound killed numerous careers and dramatically altered others. One of film's most prominent talents, Charles Chaplin, slid relatively effortlessly from one version of the medium to the next, although his most beloved character, the Tramp, did not accompany him. Yet for Chaplin, who made dozens of silent films and only five talkies, the introduction of sound diminished his box office appeal and greatly reduced his output.

Chaplin released three silent films after The Jazz Singer reached theaters: 1928's The Circus, 1931's City Lights, and 1936's Modern Times. Since the latter used some elements of pre-recorded sound (including the song, "Smile"), it was more of a hybrid, making City Lights Chaplin's farewell bow to the silent era. It's fitting that his final silent effort was also his greatest film. Although The Gold Rush, Modern Times, and even The Great Dictator all have their defenders, for its mix of physical humor and tender, heartbreaking poignancy, City Lights can't be beaten. It's an altogether wonderful gem, and one of the five best films the silent era has to offer.

When Chaplin released The Circus in 1928, there was not an inordinate amount of pressure on him to give up his silent ways. Talkies were growing in popularity, but they had not yet attained pre-eminence; silent films still outnumbered them by more than 10-to-1. (In fact, the Academy's awarding of an honorary Oscar to Chaplin for The Circus was a tacit admission that they recognized the end of an era.) Things were different in 1931, however. That was the year that Frankenstein and Dracula used sound and video to chill audiences. The pendulum had nearly completed its swing in the other direction, with only a pitiful few dozen silent films being released, compared to many hundreds with sound. Chaplin was stubborn, and for that we can be thankful. City Lights is the quintessential silent film - sound would have ruined it. Had Chaplin made an early transition to talkies, this masterpiece would never have reached theaters.

Chaplin began wearing the quadruple hat of actor/director/producer/writer for eight shorts in 1916, just two short years after he came to Hollywood. In 1923, he made his feature-length directorial debut in A Woman of Paris - an odd choice because it was a melodrama in which Chaplin only made a token, uncredited appearance. For The Gold Rush (1925), the filmmaker handled an amazing six tasks, including producing, writing, editing, and composing. It was also the first full-length movie in which Chaplin directed himself. The Circus, City Lights, and Modern Times followed.

Chaplin's most enduring alter-ego was the Tramp. The beloved character first appeared in 1914 (catapulting the actor to stardom) and made his swan song in Modern Times (Chaplin did not carry the inherently silent personality into the sound era). Today, many movie-lovers believe Chaplin and the Tramp to be synonymous. When they think of the multitalented silent thespian, they see a disheveled figure with a paintbrush mustache waddling down a street. Few characters in the history of cinema are as instantly recognizable.

The Tramp is front and center in City Lights. One night when he's out and about town, he prevents a drunk Millionaire (Harry Myers) from drowning himself. The Millionaire, realizing his folly, is grateful, and brings the Tramp home with him, much to the chagrin of the Millionaire's snobbish butler (Allan Garcia). In the morning, when the Millionaire has sobered up, he doesn't remember the Tramp. By nightfall, however, with the drink again in his veins, he greets his friend with warmth and good spirits, while the butler looks on with a pained expression.

Meanwhile, the Tramp has fallen in love with a gentle, blind Flower Girl (Virginia Cherrill). Using his last cent, he buys a flower from her and wears it in the lapel of his natty suit. The next day, flush with money provided by the Millionaire, he purchases her entire stock, then drives her home in his new friend's car. She mistakenly thinks he's a wealthy man, and that impression is re-enforced when he provides her with the money to pay her rent and travel abroad to have an operation to cure her blindness.

City Lights' ending is well known and has justly been described as one of the most perfect conclusions in the history of cinema. The Tramp, recently released from prison (where he has been serving a term for stealing), encounters the Flower Girl, who can now see. At first, she doesn't recognize her benefactor, and takes pity on him because he looks poor and down-and-out. But, when she touches his hand, she understands who he is. Title cards are used to convey their sparse dialogue. (Her: "You?" Him: "You can see now?" Her: "Yes. I can see now.") Yet words would have ruined the moment, which features heartbreaking performances through body language and facial expression from both Chaplin and Cherrill. It is an indelible exchange that is often presented as a clip to illustrate the strength of silent films, but is inexpressibly powerful when shown in the context of the entire movie.

As compelling as City Lights' dramatic element is, the film is still primarily a comedy, and features several instances of Chaplin at his best. Indeed, the movie is pieced together like a series of shorts with several common characters. It's an episodic endeavor, with a host of classic comic vignettes. The film opens with the Tramp sleeping in the lap of a statue. When he tries to get up, his pants become caught on the statue's sword. Later, when the Tramp first meets the Millionaire, the two of them end up going for an unexpected swim. I usually don't laugh at physical comedy, but this scene had me in stitches. Shortly thereafter, there's a scene in which the Millionaire pours two bottles of champagne down the Tramp's pants. Then there's the boxing match, which transpires later in the film. It's a perfectly timed example of dodging, feinting, weaving, and dodging some more as the hopelessly overmatched Tramp tries to win a purse in the ring.

There is a paradoxical aspect to City Lights. When recalling its charm and humor, I don't think of it as a "silent film." Instead, it springs to mind as an example of a spry narrative brought to life by wonderful performances and talented direction. (Of course, with Chaplin's rich and varied musical score providing accompaniment, it's not really "silent" anyway.) Yet the means of City Lights' presentation - without talking - is a necessary part of its charm and power. Dialogue can become a crutch. Here, the characters must emote their feelings without voice, and it results in some astounding moments. Then, of course, there's the slapstick physical comedy. This sort of thing can seem forced and silly when done with sound, but has a more relaxed, natural feel in a silent context (because both the means of its presentation and its content are obviously divorced from reality). Some things work better without sound than with it (the reverse is also true - consider the musical, for instance), and Chaplin's brand of comedy is one of these. Rarely does a modern-day motion picture generate laughs using this approach. (One exception: the beginning of Stanley Tucci's The Impostors, which is designed as an homage to the Chaplin/Keaton silents.)

Of all Chaplin's films (with the possible exception of Modern Times), City Lights offers the fullest characterization of the Tramp. He's a loner who comes and goes almost like a dream figure or a drunken angel. Without family, friends, or a place to live, he stands outside of our reality, sometimes trying to fit in and sometimes not caring whether or not he does. Yet, like a child, he is a complete innocent with a pure heart and the best motives. The most touching thing about his relationship with the Flower Girl is that, because she is blind, she cannot see his shabby appearance and does not judge him the way others do. (In an odd way, this echoes the blind man's friendship with the creature in Mary Shelly's Frankenstein.) And, when her sightlessness has been lifted, her attitude does not change. Her new eyes see past the hobo's clothing.

In a time when blockbusters mistake "bigger" and "louder" with "better", silent films are becoming passé. Few children (teenagers especially) have any desire to watch a black-and-white movie, let alone one in which the characters don't talk. It's a pity, because those who refuse to view silent films are denying themselves a source of great pleasure. There's an indefinable magic associated with exploring this arm of cinema, whether it's in absorbing the spectacle and virtuosity of Battleship Potemkin, seeing the nightmarish images of Nosferatu or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, or experiencing the marriage of potent drama and high comedy in City Lights. For those who wish to introduce a friend, child, or loved one to the vast library of silent films, I recommend this Chaplin picture as a starting point. Few movies leave as lasting an impression, and anyone who dismisses the silent era after viewing this treasure deserves all the Godzillas and Wild Wild Wests that he or she can inhale.

City Lights (United States, 1931)

Cast: Charlie Chaplin, Virginia Cherrill, Harry Myers, Florence Lee, Allan Garcia, Hank Mann

Screenplay: Charles Chaplin

Cinematography: Mark Marklatt, Gordon Pollock, Roland Totheroh

Music: Charles Chaplin

U.S. Distributor: United Artists

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Nothing Objectionable)

Genre: DRAMA/COMEDY

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017)

- Apartment, The (1969)

- Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day (2008)

- (There are no more better movies of Charlie Chaplin)

- (There are no more worst movies of Charlie Chaplin)

- (There are no more better movies of Virginia Cherrill)

- (There are no more worst movies of Virginia Cherrill)

- (There are no more better movies of Harry Myers)

- (There are no more worst movies of Harry Myers)

Comments