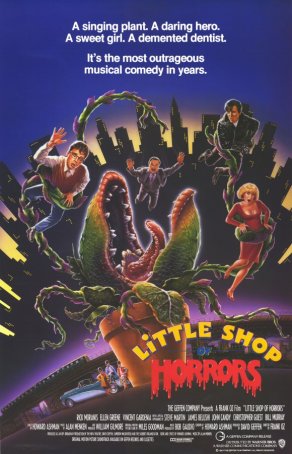

Little Shop of Horrors (re-review) (United States, 1986)

October 27, 2017

Spoilers Ahoy! This review talks in detail about plot points, including the ending, so if you haven’t seen either the play or the movie and want to experience it without knowing beforehand what happens, I suggest avoiding this review.

In late 1959, using his particular brand of low-budget filmmaking, Roger Corman did what many considered impossible: he completed a movie in two days. Called The Little Shop of Horrors, it attained a cult fandom over the course of the next two decades. Although making almost nothing during a short, ignominious theatrical run, it found an audience during TV airings and, with its dark, campy humor, attracted a small-but-loyal group of adherents. Today, Corman’s black-and-white picture is known primarily for two things: it marked one of Jack Nicholson’s early roles and it inspired Howard Ashman and Alan Menken’s musical play, Little Shop of Horrors.

The play, which was surprisingly faithful in its overall story to Corman’s movie, debuted Off-Off-Broadway in 1982 before moving Off-Broadway a month into its run. Almost from the outset, chief financier David Geffen had thoughts of a movie – a possibility Ashman wasn’t averse to. Initially, Geffen scored a coup by catching the interest of Martin Scorsese but, by the time the film went before the cameras, Scorsese was either unavailable or no longer interested. Frank Oz replaced him. The movie had a long, although not especially arduous shoot, with everything being shot on the 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios in England, where the cavernous open space was turned into a replica of New York’s Skid Row circa 1960.

No discussion about Little

Shop of Horrors’ production history would be complete without mentioning

the ending. As initially filmed, it mirrored the stage play, including the

deaths of Seymour and Audrey and the triumph of the plant. Although Oz and

Ashman were satisfied with this conclusion, neither producer Geffen nor

audiences were willing to accept it. Early previews were disastrous and

Oz/Ashman realized that, unless they rewrote the ending, Warner Brothers most

likely wouldn’t open the movie. In order to make the necessary changes, a

lavish “monster movie” sequence, in which Audrey II rampaged through New York,

had to be jettisoned, taking along with it approximately one-quarter of Little Shop’s ballooning budget. For

many years, the “lost ending” became an obsession among the film’s faithful. (I

remember seeing stills of it in a late ’80s issue of Cinefantastique.) A black-and-white workprint of the ending was

originally included on the 1997 DVD release – until copyright-holder Geffen had

the DVD recalled and the deleted scenes removed. Subsequently, a color copy of

the original ending was uncovered and, after being cleaned up, it was made

available as part of a 2012 Director’s Cut Blu-Ray edition. Now those who are

curious can watch both the Theatrical and the Unreleased versions side-by-side

and determine which works better. I have some thoughts about this that I will

share later in this review.

No discussion about Little

Shop of Horrors’ production history would be complete without mentioning

the ending. As initially filmed, it mirrored the stage play, including the

deaths of Seymour and Audrey and the triumph of the plant. Although Oz and

Ashman were satisfied with this conclusion, neither producer Geffen nor

audiences were willing to accept it. Early previews were disastrous and

Oz/Ashman realized that, unless they rewrote the ending, Warner Brothers most

likely wouldn’t open the movie. In order to make the necessary changes, a

lavish “monster movie” sequence, in which Audrey II rampaged through New York,

had to be jettisoned, taking along with it approximately one-quarter of Little Shop’s ballooning budget. For

many years, the “lost ending” became an obsession among the film’s faithful. (I

remember seeing stills of it in a late ’80s issue of Cinefantastique.) A black-and-white workprint of the ending was

originally included on the 1997 DVD release – until copyright-holder Geffen had

the DVD recalled and the deleted scenes removed. Subsequently, a color copy of

the original ending was uncovered and, after being cleaned up, it was made

available as part of a 2012 Director’s Cut Blu-Ray edition. Now those who are

curious can watch both the Theatrical and the Unreleased versions side-by-side

and determine which works better. I have some thoughts about this that I will

share later in this review.

Little Shop of Horrors tells the story of a downtrodden nerd named Seymour Krelborn (Rick Moranis) who lives in the basement of his workplace, Mushnik's Flower Shop. Mr. Mushnik (the late Vincent Gardenia) treats Seymour like dirt, causing Seymour to bemoan his fate: "I keep askin' God what I'm for, And He tells me 'Gee, I'm not sure.'" The other employee at the "God and customer forsaken store" is the platinum blond bimbo Audrey (Ellen Greene), with whom Seymour is hopelessly in love. Audrey secretly fantasizes about living a life with Seymour as her husband, but doesn't reveal her dreams because her boyfriend, a sadistic dentist named Orin Scrivello, D.D.S (Steve Martin), wouldn't like it.

For Seymour, everything is about to change. A strange and exotic plant he recently bought is beginning to blossom into something the likes of which no one has ever before seen. It's a sickly thing, however, because it responds only to one kind of food: fresh blood. After draining himself on a daily basis via cuts to his fingers, Seymour is rewarded by a spurt of growth from his horticultural oddity, Audrey II. Suddenly, the plant is the talk of the city, Seymour is famous, and Mushnik's Flower Shop is flooded with customers. But, when Seymour cannot keep up with the plant's insatiable appetite, Audrey II makes a suggestion (yes, it can talk, using the voice of the Four Tops' Levi Stubbs): ice the nasty, abusive Orin and use him as food. ’Cause if Seymour feeds it, Audrey II can “grow up big and strong.” When that happens, it can fill all of Seymour’s dreams.

Killing Orin, however, proves to be difficult for Seymour –

more because of basic incompetence than moral compunctions. Orin, however,

helps out by accidentally inhaling more laughing gas than he should. Seymour

lugs the lifeless body back to the shop, cuts it up in a back alley (an act

witnessed by a suitably horrified Mr. Mushnik), and feeds Audrey II. Soon

thereafter, with Orin now permanently out-of-the-picture, Seymour and Audrey

have a heart-to-heart that ends with a soaring duet and a kiss. But, even

though meek Seymour is getting what comes to him, he has two problems: Mushnik

knows too much (and therefore becomes supper for the plant) and Audrey II isn’t

just some fly trap on steroids – it’s a “mean, green mother from outer space”

and it’s bent on world domination.

Killing Orin, however, proves to be difficult for Seymour –

more because of basic incompetence than moral compunctions. Orin, however,

helps out by accidentally inhaling more laughing gas than he should. Seymour

lugs the lifeless body back to the shop, cuts it up in a back alley (an act

witnessed by a suitably horrified Mr. Mushnik), and feeds Audrey II. Soon

thereafter, with Orin now permanently out-of-the-picture, Seymour and Audrey

have a heart-to-heart that ends with a soaring duet and a kiss. But, even

though meek Seymour is getting what comes to him, he has two problems: Mushnik

knows too much (and therefore becomes supper for the plant) and Audrey II isn’t

just some fly trap on steroids – it’s a “mean, green mother from outer space”

and it’s bent on world domination.

Ashman was credited with Little Shop’s screenplay and a majority of the dialogue was from the stage musical. Oz didn’t make any major changes, although he often moved the action out of the store and into the nearby environs to make things less claustrophobic. Four songs from the musical were excised. Two were significantly changed (“Ya Never Know” became “Some Fun Now”; “The Meek Shall Inherit” was chopped up) and one new one was added (“Mean Green Mother from Outer Space”). “Don’t Feed the Plants”, the play’s finale, although recorded and filmed, was removed out of necessity when the ending was changed.

Unlike many screen musicals, Little Shop of Horrors didn’t require extensive choreography. There’s a lot of singing but not much dancing. The most complex number is “Skid Row (Downtown)”, which includes a large number of extras roaming around the set. Oz kept camera movements clean and conventional, showing a preference for long takes. The most ambitious of these occurs during a bridge between “Somewhere That’s Green” and “Some Fun Now”, when the camera pulls back from Audrey posing in her ground floor apartment window, pans left then up, and zeroes in on the three chorus girls, who are frolicking on a roof.

Oz’s use of practical special effects (he has stated there were only two optical effects in the theatrical release) is one reason why the movie has stood the test of time. The animatronic Audrey II, which required sixty operators in its largest iteration, looks as good as any modern CGI creation. Visually, Little Shop of Horrors is timeless and many of the catchy songs will be familiar to those with only a passing knowledge of stage musicals. “Suddenly Seymour” in particular has been sung in everything from talk shows to Glee. The songs in Little Shop of Horrors were why Disney allowed Menken and Ashman to make The Little Mermaid a musical. (And The Little Mermaid begat Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and a long line of animated classics.)

Thematically, one could argue that Little Shop of Horrors has more relevance today than when it was

released in 1986. The plant uses the joint lures of celebrity and wealth to seduce

Seymour. In “Skid Row”, the protagonist sings about moving “heaven and hell to

get outta here.” Later, when convincing him to commit murder, Audrey II

promises Seymour a variety of enticements. Some of these are financial (a

Cadillac, dining out for every meal, a room at the Ritz) but many relate to

fame (TV guest appearances, dates with actresses, etc.). Later, in “The Meek

Shall Inherit”, the inducements skew toward exposure: lecturing tours, the

cover of Life Magazine, the first

weekly gardening show on a network. In the mid-1980s, the concept of having “15

minutes of fame” was pursued by only a small percentage of people. Today, in

the age of the Kardashians and their ilk, there’s a national obsession with

celebrity – something predicted by Little

Shop of Horrors 30 years ago. Seymour’s quest for fame and its ugly

consequences may resonate more strongly with contemporary audiences than they did

at the height of the Reagan Revolution.

Thematically, one could argue that Little Shop of Horrors has more relevance today than when it was

released in 1986. The plant uses the joint lures of celebrity and wealth to seduce

Seymour. In “Skid Row”, the protagonist sings about moving “heaven and hell to

get outta here.” Later, when convincing him to commit murder, Audrey II

promises Seymour a variety of enticements. Some of these are financial (a

Cadillac, dining out for every meal, a room at the Ritz) but many relate to

fame (TV guest appearances, dates with actresses, etc.). Later, in “The Meek

Shall Inherit”, the inducements skew toward exposure: lecturing tours, the

cover of Life Magazine, the first

weekly gardening show on a network. In the mid-1980s, the concept of having “15

minutes of fame” was pursued by only a small percentage of people. Today, in

the age of the Kardashians and their ilk, there’s a national obsession with

celebrity – something predicted by Little

Shop of Horrors 30 years ago. Seymour’s quest for fame and its ugly

consequences may resonate more strongly with contemporary audiences than they did

at the height of the Reagan Revolution.

There’s no way to describe the casting of Seymour and Audrey other than “perfect.” At the time, Moranis was best-known for his work on “SCTV” and an appearance in Ghostbusters. His biggest roles – Spaceballs, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, and Parenthood – were yet to come. He nails the role of nerdy, bespectacled Seymour but does something with the part that neither Ashman nor Oz expected: he makes Seymour incredibly likable. In most circumstances, that wouldn’t be a detriment, but it’s a problem when the plan is to have the character consumed by his greed and killed off. Likewise, Ellen Greene provides an adorable, helium-voiced Audrey. Greene knew the character inside-out, having originated her on stage in 1982 before reprising her in London. She and Moranis have tremendous chemistry; one reason why “Suddenly, Seymour” is the film’s standout musical number is because of the emotion in their interaction (which culminates in the long-awaited kiss).

When performing an autopsy about why the “Don’t Feed the Plants” ending doesn’t work in the movie, three factors can be cited: (1) the actors make their characters too congenial for an audience to accept their deaths, (2) close-ups magnify their humanity, and (3) death in a movie has greater permanence than in a stage play, where the actors come out at the end to take a bow. In concert, these elements make the decision to kill Audrey and Seymour brutal for any audience. Those deaths transform Little Shop of Horrors from a toe-tapping, frothy horror-musical-comedy into a grim, dark experience. The movie is no fun after Audrey dies.

Little Shop of Horrors’

supporting cast is chock-full of well-known comedians getting a little face

time. Steve Martin, with about four scenes and one musical number (the

unforgettable “Dentist!”) has the most visibility; Martin’s appearance took

about six weeks to film. John Candy (playing a host for “Skid Row Radio”),

Christopher Guest (the first customer to notice Audrey II in Mushnik’s window),

James Belushi (as marketing guru Patrick Martin), and Bill Murray (as the

masochistic patient who visits Martin’s dentist) all contribute. As Mushnik,

character actor Vincent Gardenia provides the only non-singing performance with

any significant dialogue. Tichina Arnold, Michelle Weeks, and Tisha Campbell are

Crystal, Ronette, and Chiffon, Little

Shop’s “Skid Row Supremes.” And the 4 Tops’ Levi Stubbs gives Audrey II an

unforgettable bass voice.

Little Shop of Horrors’

supporting cast is chock-full of well-known comedians getting a little face

time. Steve Martin, with about four scenes and one musical number (the

unforgettable “Dentist!”) has the most visibility; Martin’s appearance took

about six weeks to film. John Candy (playing a host for “Skid Row Radio”),

Christopher Guest (the first customer to notice Audrey II in Mushnik’s window),

James Belushi (as marketing guru Patrick Martin), and Bill Murray (as the

masochistic patient who visits Martin’s dentist) all contribute. As Mushnik,

character actor Vincent Gardenia provides the only non-singing performance with

any significant dialogue. Tichina Arnold, Michelle Weeks, and Tisha Campbell are

Crystal, Ronette, and Chiffon, Little

Shop’s “Skid Row Supremes.” And the 4 Tops’ Levi Stubbs gives Audrey II an

unforgettable bass voice.

I’m glad the Director’s Cut exists. It provides an opportunity for viewers to see the filmmakers’ original vision and compare it to what was released. But it’s really only for purists or those who have trouble coping with the consideration that what works on stage doesn’t always work on screen. I’m in the camp of those who believe the theatrical cut makes for a better movie experience. When it comes to understanding audience reaction, Geffen was better positioned than Oz or Ashman, who were too close to the original material. To this day, Oz regrets not having been able to release the film with “Don’t Feed the Plants” intact (and, when one sees the spectacle of the miniature work, his disappointment is understandable) but, to his credit, he realized the necessity of having done what he and Ashman did.

During the 30 years since its release, I have seen Little Shop of Horrors perhaps eight or nine times. Two of those have been the Director’s Cut (once on its release in 2012 and another time preparing for this review). The rest have been the theatrical version. I own (and listen to) both the Off-Broadway Cast Recording and the Motion Picture Soundtrack. The movie has proven itself to be among the most rewatchable of films and, every time I see it, I have a greater appreciation for the craft and effort that went into its making. Although set around 1960 and made in 1986, the entertainment value of this production is timeless.

Little Shop of Horrors (re-review) (United States, 1986)

Cast: Rick Moranis, Ellen Greene, Vincent Gardenia, Steve Martin, Tichina Arnold, Michelle Weeks, Tisha Campbell, Levi Stubbs

Home Release Date: 2017-10-27

Screenplay: Howard Ashman

Cinematography: Robert Paynter

Music: Alan Menken, Howard Ashman

U.S. Distributor: Warner Brothers

U.S. Release Date: 1986-11-26

MPAA Rating: "PG-13" (Violence, Profanity)

Genre: Musical

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- Little Shop of Horrors (1986)

- (There are no more better movies of Rick Moranis)

- My Blue Heaven (1990)

- (There are no more worst movies of Rick Moranis)

- Little Shop of Horrors (1986)

- Pump Up the Volume (1990)

- (There are no more better movies of Ellen Greene)

- One Fine Day (1996)

- (There are no more worst movies of Ellen Greene)

- Little Shop of Horrors (1986)

- (There are no more better movies of Vincent Gardenia)

- (There are no more worst movies of Vincent Gardenia)

Comments