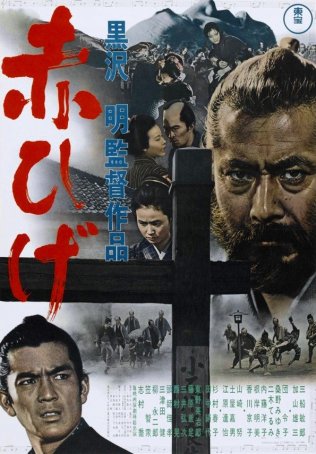

Red Beard (Japan, 1965)

December 04, 2018

For legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, Red Beard represented the end of an era. Not only was it the last film he would make in black-and-white but it represented the end of a 16-film collaboration with Toshiro Mifune. Across the landscape of the 20th century, few actor/director pairs were more recognizably linked than these two; they even died within a year of one another. For most viewers, the Kurosawa/Mifune oeuvre is strongly associated with samurai. This isn’t surprising, considering that some of the titles are Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, The Hidden Fortress, and Yojimbo. But for those anticipating sword-play and violence from Red Beard, this subtle gem will confound expectations. The movie shows the humanist side of Kurosawa (reminiscent in some ways of Ikiru) and depicts a gentler facet of Mifune.

The film took two years to make and the length of filming is said to be one of the things that caused a rift between the director and his regular star. Any behind-the-scenes problems don’t make it to the screen, however. The production values are top-notch with the sets displaying the highest level of authenticity and the winter scenes demanding real snow, not the fake kind favored by most filmmakers.

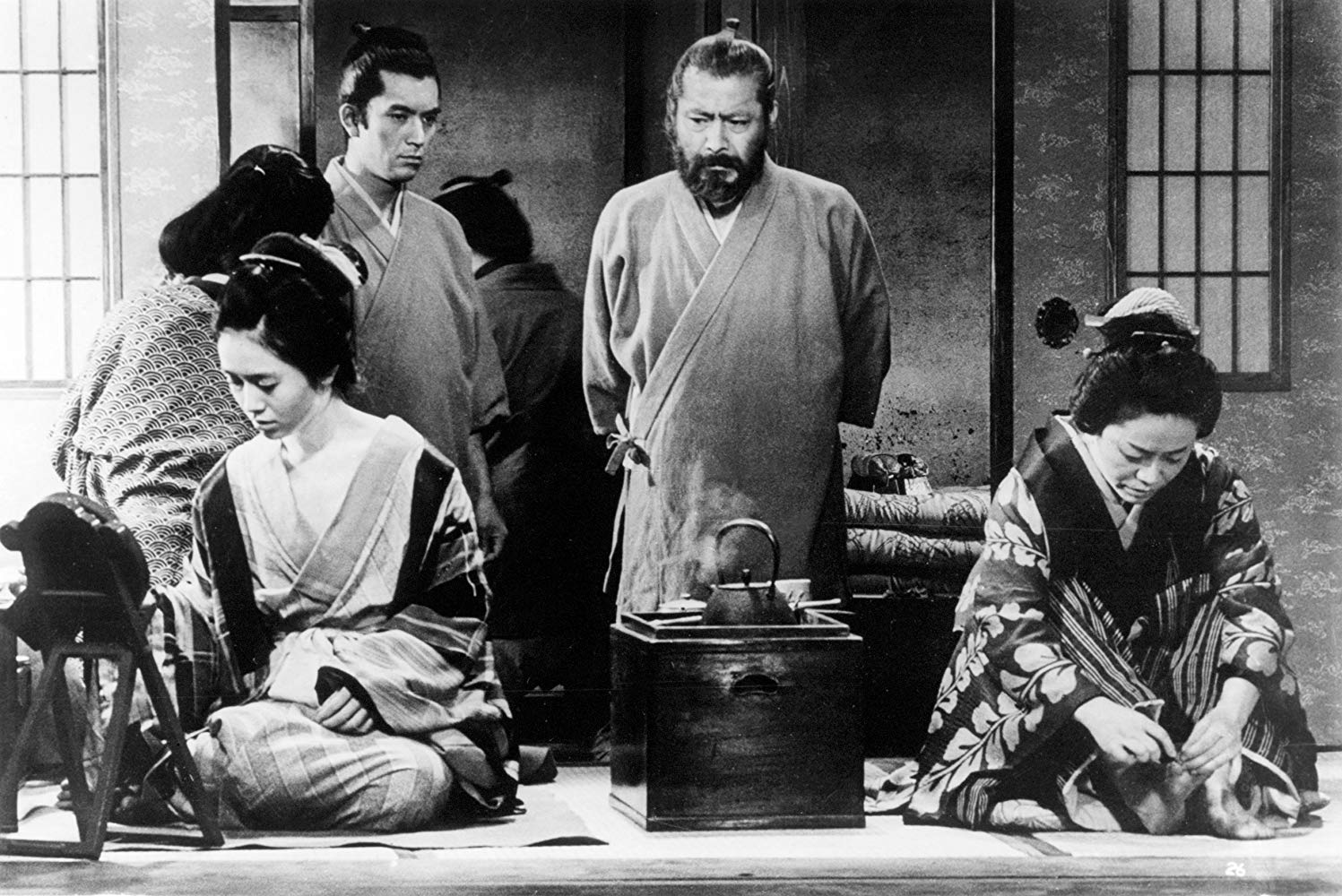

The story, which is a belated coming-of-age tale, transpires

in rural Japan during the 19th century. A young, ambitious doctor by the name

of Noboru Yasumoto (Yuzo Kayama) has been assigned to the village clinic to

serve as an apprentice to the grizzled veteran doctor, Kyojo Niide a.k.a. “Red

Beard” (Mifune). He’s none-too-happy about the appointment, having expected to

serve as the personal physician of a shogun. Determined to be dismissed, he

disobeys orders and refuses requests, but Niide shows extraordinary patience,

seeing something in the young man that Yasumoto doesn’t recognize in himself.

Sure enough, the more he interacts with patients, the more empathetic he

becomes until he dons a doctor’s uniform and develops the same kinds of deep

bonds with his charges that Niide exhibits.

The story, which is a belated coming-of-age tale, transpires

in rural Japan during the 19th century. A young, ambitious doctor by the name

of Noboru Yasumoto (Yuzo Kayama) has been assigned to the village clinic to

serve as an apprentice to the grizzled veteran doctor, Kyojo Niide a.k.a. “Red

Beard” (Mifune). He’s none-too-happy about the appointment, having expected to

serve as the personal physician of a shogun. Determined to be dismissed, he

disobeys orders and refuses requests, but Niide shows extraordinary patience,

seeing something in the young man that Yasumoto doesn’t recognize in himself.

Sure enough, the more he interacts with patients, the more empathetic he

becomes until he dons a doctor’s uniform and develops the same kinds of deep

bonds with his charges that Niide exhibits.

Read Beard unfolds as a series of episodes, each featuring a patient with a story to tell. Sometimes, it is enacted by way of flashback. On other occasions, the camera focuses on the teller as (s)he relates his (or her) tale. Although each of these fragments functions as a stand-alone vignette, their aggregation contributes to Yasumoto’s development as a doctor and, more importantly, a person. He also learns from Red Beard, whose seemingly unbreachable confidence proves to be anything but that as he gripes about the “limitations of medicine” and how the two greatest barriers to better health care are “poverty and ignorance.” Made in 1965, it’s amazing how much insight Red Beard shows about concerns that are relevant in 2018.

The majority of the material found in Red Beard was adapted by Kurosawa and three other writers from a

collection of short stories by Shugoro Yamamoto. That’s not the only source,

however. A key subplot was inspired by Dostoevsky’s Humiliated and Insulted. It concerns a 12-year old girl, Otoyo

(Terumi Niki), who is taken from a brothel by Niide and Yasumoto after she

falls ill. She becomes the young doctor’s first solo patient and he discovers

that not only is she suffering from a fever but she has been deeply traumatized

by her experiences working as a sex slave. The way in which Yasumoto cares for

her and her reciprocal nursing of him after he falls sick functions as the

film’s emotional core. While Red Beard and various others contribute to

Yasumoto’s transformation, no one is more important than Otoyo.

The majority of the material found in Red Beard was adapted by Kurosawa and three other writers from a

collection of short stories by Shugoro Yamamoto. That’s not the only source,

however. A key subplot was inspired by Dostoevsky’s Humiliated and Insulted. It concerns a 12-year old girl, Otoyo

(Terumi Niki), who is taken from a brothel by Niide and Yasumoto after she

falls ill. She becomes the young doctor’s first solo patient and he discovers

that not only is she suffering from a fever but she has been deeply traumatized

by her experiences working as a sex slave. The way in which Yasumoto cares for

her and her reciprocal nursing of him after he falls sick functions as the

film’s emotional core. While Red Beard and various others contribute to

Yasumoto’s transformation, no one is more important than Otoyo.

Although the movie’s overall tone is upbeat, concentrating as it does on Yasumoto’s conversion from a self-centered, callow youth to a man of deep feeling and principle, there is also a vein of sadness. Red Beard sees the human condition with a clear eye and recognizes how the petty concerns of the wealthy impede the funds needed to care for the poor. Toward the end, when Yasumoto announces his decision to continue working at the clinic, condemning himself and his new wife to a life of poverty, Red Beard warns him off.

Some of the individual stories are tragic. The Mantis, a

mentally ill young woman who has killed three lovers, tells Yasumoto about her

childhood abuse. A dying man, Sahachi (Tsutomu Yamazaki), relates the tale of how

his wife’s skeleton ended up buried in his yard. A young thief, Choji

(Yoshitaka Zushi), nearly dies of rat poison when his parents decide that mass

suicide is better than living with the shame of having a thief in the family.

Each of these stories is surprisingly powerful considering the limited amount

of screen time it is accorded. The movie as a whole runs three hours but

doesn’t seem nearly that long.

Some of the individual stories are tragic. The Mantis, a

mentally ill young woman who has killed three lovers, tells Yasumoto about her

childhood abuse. A dying man, Sahachi (Tsutomu Yamazaki), relates the tale of how

his wife’s skeleton ended up buried in his yard. A young thief, Choji

(Yoshitaka Zushi), nearly dies of rat poison when his parents decide that mass

suicide is better than living with the shame of having a thief in the family.

Each of these stories is surprisingly powerful considering the limited amount

of screen time it is accorded. The movie as a whole runs three hours but

doesn’t seem nearly that long.

There are moments of levity as well. One scene in particular stands out; it may have been designed with a wink-and-a-nod toward those familiar with Kurosawa and Mifune’s less sedate offerings. When rescuing Otoyo from the brothel, Red Beard must subdue a group of guards. He does so with gusto, meticulously taking each of them down, breaking arms and legs along the way. When it’s over, he mutters something about how he may have gone too far.

Read Beard can stand proudly alongside many of the other Kurosawa/Mifune partnerships. Although the master would continue to make films for another 28 years after Red Beard, he would never again achieve the same level that he did during the period of 1948 through 1965. As an elegy to a perfect fusion of directorial mastery and an actor’s indomitable screen presence, it’s hard to imagine something more memorable and affecting than Red Beard.

Red Beard (Japan, 1965)

Cast: Toshiro Mifune, Yuzo Kayama, Terumi Niki, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Tsutomu Yamazaki, Miyuki Kuwano, Yoshitaka Zushi

Home Release Date: 2018-12-04

Screenplay: Masato Ide & Hideo Oguni & Ryuzo Kikushima & Akira Kurosawa, based on the short story collection by Shugoro Yamamoto

Cinematography: Asakazu Nakai, Takao Saito

Music: Masura Sato

U.S. Distributor: Toho Company

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Nudity, Violence)

Genre: Drama

Subtitles: In Japanese with English subtitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1

- (There are no more worst movies of Toshiro Mifune)

- (There are no more better movies of Yuzo Kayama)

- (There are no more worst movies of Yuzo Kayama)

- (There are no more better movies of Terumi Niki)

- (There are no more worst movies of Terumi Niki)

Comments