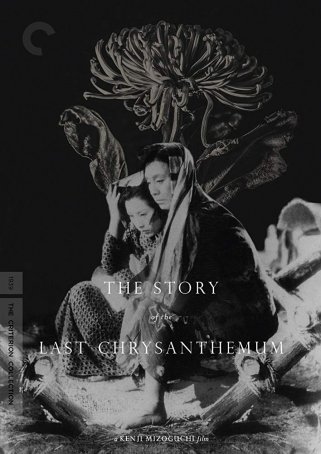

Story of the Last Chrysanthemum (Japan, 1939)

August 04, 2019

The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum offers proof that a movie doesn’t have to be new to be deeply affecting. A meditation on life, love, and sacrifice, this 1939 film is a true tear-jerker. Heartwarming at times but ultimately heartbreaking, it illustrates that love sometimes exacts a price that is painful to pay and uncomfortable to watch being paid.

If one was to look at the history of Japanese cinema, it wouldn’t take long to pick out the trio of master filmmakers: Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, and Kenji Mizoguchi. Of the three, Mizoguchi’s work is probably the least celebrated because he received less exposure in English-speaking countries than Kurosawa or Ozu. His career spanned 23 years, from the late silent era to the period when color was beginning to become the norm (although only two of his titles were filmed in that format) and, during that time, he made nearly 80 movies. His best-known works were Ugetsu and Sansho the Baliff, both of which were made toward the end of his career. The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum was among his most acclaimed pre-war efforts, although questionable preservation techniques have resulted in a less-than-pristine copy being available today. (The Criterion Collection edition features fuzzy, indistinct images and tinny audio.)

The story transpires in 1885 Japan, mostly in

the cities of Tokyo and Osaka. The main character, Kiku (Shotaro

Hanayagi), is the adopted son of the famous Kabuki actor Kikugoro Onoue

(Gonjuro Kawarazaki). Following in his father’s footsteps, Kiku appears on

stage but his performances are laughably bad. Seeking to curry favor, no one

tells him the truth, instead praising his flawed portrayals – no one, that is,

except Otoku (Kakuko Mori), a servant in his father’s household. Appreciating

her frankness and developing a fondness for her, Kiku begins to spend time with

her. (The scene where they share watermelon – with *salt* - is a gem.) When his

family notices, they sense impropriety and the potential for scandal in the

relationship and fire Otoku. An outraged Kiku breaks with his father over this

and leaves Tokyo to find Otoku.

The story transpires in 1885 Japan, mostly in

the cities of Tokyo and Osaka. The main character, Kiku (Shotaro

Hanayagi), is the adopted son of the famous Kabuki actor Kikugoro Onoue

(Gonjuro Kawarazaki). Following in his father’s footsteps, Kiku appears on

stage but his performances are laughably bad. Seeking to curry favor, no one

tells him the truth, instead praising his flawed portrayals – no one, that is,

except Otoku (Kakuko Mori), a servant in his father’s household. Appreciating

her frankness and developing a fondness for her, Kiku begins to spend time with

her. (The scene where they share watermelon – with *salt* - is a gem.) When his

family notices, they sense impropriety and the potential for scandal in the

relationship and fire Otoku. An outraged Kiku breaks with his father over this

and leaves Tokyo to find Otoku.

A year later, Kiku and Otoku are reunited. She acknowledges the sacrifice he has made to be with her and consents to be his companion. She encourages him as he attempts to restart his career with a traveling troupe of actors. After four years pass, they are still together but the bond of love has faded. They have little money and are forced to leave in meager circumstances. Otoku becomes ill but continues to work to advance Kiku’s position. When Kiku’s brother, Fuku (Kokichi Takada), comes to Osaka to perform, Otoku meets with him and brokers a deal – if she separates from Kiku, Fuku will cast him as a lead in his current play. Kiku, who has improved dramatically as an actor during his time away from Tokyo, wins raves and returns home in triumph – but without Otoku. Kiku is able to repair his relationship with his father, who surprisingly encourages him to seek out Otoku (who is dying of tuberculosis) and make amends. The movie ends with Kiku acknowledging his now-adoring public during a parade while Otoku, lying in bed and listening to the cheering of the crowds, breathes her last.

Perhaps the most immediately noticeable

aspect of The Story of the Last

Chrysanthemum is how Mizoguchi elected to shoot it. Opting for long,

unbroken takes from mid-range (there are no close-ups), the director relied on

dollies and cranes to allow the camera to move seamlessly from one location to

another. Although this approach creates a distance between the viewer and the

characters and makes us more like voyeurs than participants, it does nothing to

diminish the story’s emotional impact. Another unique technical aspect relates

to the score, which makes heavy use of percussive instruments and incorporates

everyday sounds (such as shoes striking the pavement) to create an unusual

musical accompaniment.

Perhaps the most immediately noticeable

aspect of The Story of the Last

Chrysanthemum is how Mizoguchi elected to shoot it. Opting for long,

unbroken takes from mid-range (there are no close-ups), the director relied on

dollies and cranes to allow the camera to move seamlessly from one location to

another. Although this approach creates a distance between the viewer and the

characters and makes us more like voyeurs than participants, it does nothing to

diminish the story’s emotional impact. Another unique technical aspect relates

to the score, which makes heavy use of percussive instruments and incorporates

everyday sounds (such as shoes striking the pavement) to create an unusual

musical accompaniment.

The final scene is wrenching and, although there are times during the balance of the production when Shotaro Hanayagi gives in to a tendency to overact (a hold-over from his lengthy stage career), he plays this sequence perfectly. Even without the camera getting too close, we can see the cracks in the façade as he faces the crowds while knowing that, not far away, Otoku is dying. Although their union has now been accepted by everyone, fate has stolen it away. He will never see her again. All of this is evident in Hanayagi’s expression and body language.

Although filmed eight decades ago and set in a time period more than 130 years in the past, the movie’s treatment of fame is contemporarily relevant, indicating how little some things change. Kiku spends a majority of The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum chasing this elusive quality. For an actor, fame is at least as important (if not more so) than talent and, in order to achieve it, Kiku is forced to sacrifice happiness and love. Otoku’s timeless devotion to Kiku’s success demands payment in the currency of her health and eventually her life.

The film isn’t without problems, however. The

acting is spotty; there are times when it evinces a “theatrical” quality

(actors exaggerating gestures, for example) that was common in movies made

during the silent-to-talkie transition period (mostly the 1930s). I found the

Kabuki sequences to be long and uninvolving, especially one eight-minute

performance that was nearly unbearable to sit through. The point of this scene

– to illustrate the improvements in Kiku’s acting ability – was entirely lost

on me, possibly because of my limited knowledge of and appreciation for this

art form. This is an aspect that hasn’t translated across cultures and decades.

Although it would have made sense to Japanese audiences in the 1930s, who still

saw cinema as an extension of Kabuki, it now seems like an unnecessary

indulgence. Instead of advancing the story, the Kabuki interludes (the are two

– the eight-minute one and a 3 ½-minute “encore”), bring it to a dead stop.

They are a primary reason why The

Story of the Last Chrysanthemum seems overlong. (It runs 144 minutes.)

The film isn’t without problems, however. The

acting is spotty; there are times when it evinces a “theatrical” quality

(actors exaggerating gestures, for example) that was common in movies made

during the silent-to-talkie transition period (mostly the 1930s). I found the

Kabuki sequences to be long and uninvolving, especially one eight-minute

performance that was nearly unbearable to sit through. The point of this scene

– to illustrate the improvements in Kiku’s acting ability – was entirely lost

on me, possibly because of my limited knowledge of and appreciation for this

art form. This is an aspect that hasn’t translated across cultures and decades.

Although it would have made sense to Japanese audiences in the 1930s, who still

saw cinema as an extension of Kabuki, it now seems like an unnecessary

indulgence. Instead of advancing the story, the Kabuki interludes (the are two

– the eight-minute one and a 3 ½-minute “encore”), bring it to a dead stop.

They are a primary reason why The

Story of the Last Chrysanthemum seems overlong. (It runs 144 minutes.)

Tragic love stories are nothing new. They have been around for as long as poets and storytellers have been recounting tales of romance. The cynic in me sometimes rejects these as being overly melodramatic. In this case, however, Mizoguchi’s artistry blunts the criticism. The characters feel real and their circumstances are less an attempt to manipulate a viewer’s emotions than to offer a commentary on the social and cultural standards of the day. Otoku’s sacrifice is powerful and its consequences make a forceful statement about the disconnect that can exist between fame and happiness. The effectiveness of The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum expresses why Mizoguchi deserves to be mentioned alongside Kurosawa and Ozu in the elite pantheon of Japanese filmmakers.

Story of the Last Chrysanthemum (Japan, 1939)

Cast: Shotaro Hanayagi, Kakuko Mori, Kokichi Takada, Gonjuro Kawarazaki

Home Release Date: 2019-08-04

Screenplay: Matsutaro Kawaguchi and Yoshikata Yoda, based on the novel by Shofu Muramatsu

Cinematography: Yozu Fuji, Shigeto Miki

Music: Shiro Fukai, Senji Ito

U.S. Distributor: Films Inc.

- (There are no more better movies of Shotaro Hanayagi)

- (There are no more worst movies of Shotaro Hanayagi)

- (There are no more better movies of Kakuko Mori)

- (There are no more worst movies of Kakuko Mori)

- (There are no more better movies of Kokichi Takada)

- (There are no more worst movies of Kokichi Takada)

Comments