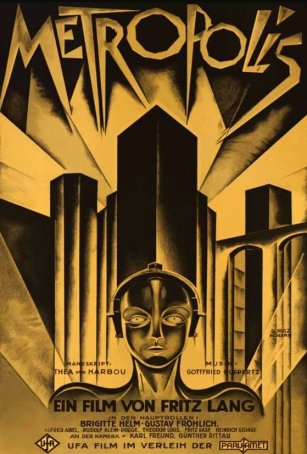

Metropolis (Germany, 1927)

January 19, 2020

Polls of the most “important” films made during the silent

era consistently rank Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

at or near the top (alongside Eisenstein’s Battleship

Potemkin and Murnau’s Nosferatu).

There’s a reason for this: seemingly every scene or image from Metropolis is recognizable in its own

right or because it has been appropriated in some form by a more recent film.

Films as iconic as Kubrick’s 2001 or

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner and as

relatively obscure as Dark City and Joe vs. the Volcano owe obvious debts to

Metropolis. Even in 2019, echoes of

it continue to abound – aspects of Alita: Battle Angel are lifted wholesale from it. The first full-length science

fiction feature, Metropolis

illustrated the kind of “spectacle” that the silver screen could offer and

paved the way for the hundreds of eye-popping productions that would follow in

its wake. Metropolis has earned its

place in history more because of its influence over future generations of

filmmakers and its overall importance to the medium than because of its

unremarkable story and simplistic view of sociopolitical issues.

That’s not to say the story is always easy to follow,

although the most recent reconstruction (more on that later) does its best to

restore the narrative flow devised by Lang when he assembled his final cut.

Transpiring in 2026, Metropolis envisions

a future where income disparities have become so great that the human race is

divided into two classes. The workers live in an underground city of tenements

and 10-hour clocks and only emerge above ground to work long, grueling days

keeping a vast array of nonsense machines working. The purpose of the machines

it to provide light and power to the vast city of Metropolis, a paradise for wealthy

pleasure seekers. With its maze of glass-and-metal buildings that touch the

sky, Metropolis is a technical marvel marred only by the knowledge of the

flesh-and-blood toll that goes into keeping it alive.

The film’s protagonist, Freder (Gustav Frohlich), is the son

of the ruler of Metropolis, Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel). Like most of his

class, he is callow and clueless, until a chance encounter with the mysterious

Maria (Brigitte Helm), arouses his curiosity about his “brothers” and “sisters”

in the undercity. Changing places with a worker who goes by the number of

“11811” (Erwin Biswanger), Freder insinuates himself into the lower class and

discovers the hardship and deprivations they endure. After working only one

shift, he is as much a zombie as they are, trudging lifelessly from one place

to the next. At a rally, he again encounters Maria and learns that she preaches

a doctrine of peace and patience to the workers, encouraging them with a

prophesy of the coming “Mediator” who will use the “heart” to join the “hand

and mind.” She believes Freder to be the Mediator.

The film’s protagonist, Freder (Gustav Frohlich), is the son

of the ruler of Metropolis, Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel). Like most of his

class, he is callow and clueless, until a chance encounter with the mysterious

Maria (Brigitte Helm), arouses his curiosity about his “brothers” and “sisters”

in the undercity. Changing places with a worker who goes by the number of

“11811” (Erwin Biswanger), Freder insinuates himself into the lower class and

discovers the hardship and deprivations they endure. After working only one

shift, he is as much a zombie as they are, trudging lifelessly from one place

to the next. At a rally, he again encounters Maria and learns that she preaches

a doctrine of peace and patience to the workers, encouraging them with a

prophesy of the coming “Mediator” who will use the “heart” to join the “hand

and mind.” She believes Freder to be the Mediator.

Meanwhile, Fredersen, after being informed of growing worker

unrest, devises a scheme that will allow him to crack down on the workers

without seeming to be overzealous in his response. He seeks the aid of a

sometimes-advisor, a mad scientist named Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), who is

eager to show Fredersen his latest invention, the so-called Machine Man (also

Brigitte Helm). At the moment, the robot looks like a mechanical representation

of a person (and, in fact, inspired the design of C3PO from Star Wars) but, given 24 hours, Rotwang

asserts he can make the Machine Man indistinguishable from a human. Fredersen

agrees to back Rotwang if he will create a doppleganger of Maria who can be

used to foment unrest. His plan is that if the workers riot and destroy the

machines, severe reprisals will be seen as justifiable. Fredersen doesn’t

realize that his son is embedded with the workers or that Rotwang has his own

revenge-driven agenda.

Meanwhile, Fredersen, after being informed of growing worker

unrest, devises a scheme that will allow him to crack down on the workers

without seeming to be overzealous in his response. He seeks the aid of a

sometimes-advisor, a mad scientist named Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), who is

eager to show Fredersen his latest invention, the so-called Machine Man (also

Brigitte Helm). At the moment, the robot looks like a mechanical representation

of a person (and, in fact, inspired the design of C3PO from Star Wars) but, given 24 hours, Rotwang

asserts he can make the Machine Man indistinguishable from a human. Fredersen

agrees to back Rotwang if he will create a doppleganger of Maria who can be

used to foment unrest. His plan is that if the workers riot and destroy the

machines, severe reprisals will be seen as justifiable. Fredersen doesn’t

realize that his son is embedded with the workers or that Rotwang has his own

revenge-driven agenda.

The politics of Metropolis

are straightforward and decidedly Marxist in their leanings. The movie is a

thinly veiled fable about the overburdened prolitariat rising against a corrupt

bourgeoisie. There are also strong religious tones with unambiguous references

to both the Tower of Babel and the Whore of Babylon (from “Revelation”).

Science fiction often functions allegorically; in Metropolis, there’s little subtlety to this. H.G. Wells, whom Lang

cited as an “influence” on Metropolis

(along with Mary Shelly and German Expressionism), wrote a review in which he

lambasted the movie as “foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical

progress and progress in general.”

The film’s length (the reconstructed version, which is

representative of the version Lang premiered at the grand opening) lends itself

to pacing issues. Certain scenes have a tendency to go on for too long (in some

cases, this is done to highlight visual elements) and some of the subplots and

secondary characters aren’t sufficiently developed for those aspects to work. Metropolis is effective at building

suspense. Even when seen today, the flooding of the underground city (with the

attempts of various characters to survive the rising waters á là Titanic) offers a thrilling 15 minutes.

It’s easy to forgive those aspects of Metropolis

that don’t work when considering the many that do.

Like many silent films, this one focuses more strongly on

visual impact than the more mundane storytelling building blocks of narrative

and character motivation. Some contemporaneous critics (like Wells) recognized

this as an evident weakness. The film received nearly unanimous praise for its

technical accomplishments but wasn’t always as well regarded for the acting and

story. Although Brigitte Helm was often (deservedly) singled out for her

memorable performance (both as the Machine Man and Maria), Gustav Frohlich

didn’t fare as well. This is understandable – instead of standing out as a hero

should, he has a tendency to fade into the background when he’s not going

over-the-top.

Like many silent films, this one focuses more strongly on

visual impact than the more mundane storytelling building blocks of narrative

and character motivation. Some contemporaneous critics (like Wells) recognized

this as an evident weakness. The film received nearly unanimous praise for its

technical accomplishments but wasn’t always as well regarded for the acting and

story. Although Brigitte Helm was often (deservedly) singled out for her

memorable performance (both as the Machine Man and Maria), Gustav Frohlich

didn’t fare as well. This is understandable – instead of standing out as a hero

should, he has a tendency to fade into the background when he’s not going

over-the-top.

Metropolis earned

Lang (a German Jew) praise from an unwanted source: Joseph Goebbels, who

referenced in a speech the film’s central message about the heart being needed

to mediate between the head and the hand. Hitler was also a fan, expressing a

desire for Lang to make Nazi propaganda movies and offering to make him an

“honorary Aryan.” The film’s writer and Lang’s then-wife, Thea von Harbou,

became a Nazi sympathizer. The director responded by divorcing Harbou and

fleeing first to France then to Hollywood.

Lang was known for making long films; the original cut of Metropolis was no exception. However, in

order to make the movie more commercially viable, the distributors recut the

print, excising a third of the material and reworking the story to make it more

streamlined and less “pro-Communist.” Although the version Lang showed at the

premiere was 153 minutes in length, the German theatrical release was 116

minutes and Paramount’s U.S. edition was slimmed down to 106 minutes. The first

home video version, available in 1984, ran 83 minutes (based on a 1936 cut). A

2001 partial reconstruction increased the running time to about two hours. A

major find of nearly all the lost footage allowed a nearly complete copy (with

less than five total minutes of scenes still missing) to be made available in

2010.

Lang was known for making long films; the original cut of Metropolis was no exception. However, in

order to make the movie more commercially viable, the distributors recut the

print, excising a third of the material and reworking the story to make it more

streamlined and less “pro-Communist.” Although the version Lang showed at the

premiere was 153 minutes in length, the German theatrical release was 116

minutes and Paramount’s U.S. edition was slimmed down to 106 minutes. The first

home video version, available in 1984, ran 83 minutes (based on a 1936 cut). A

2001 partial reconstruction increased the running time to about two hours. A

major find of nearly all the lost footage allowed a nearly complete copy (with

less than five total minutes of scenes still missing) to be made available in

2010.

Over the years, Metropolis has developed a reputation to match the filmmakers’ ambitions for it. It stands out from most surviving silent films in both its epic scope and ability to craft scenes and images that remain effective nearly 100 years after Lang first committed them to celluloid. Metropolis was completed toward the end of the silent era – within a few years after its completion, Lang would make his first “talkie,” the disturbing M, starring Peter Lorre – and it remains one of the most accessible films of its kind to show to contemporary audiences. Its focus on spectacle makes it a precursor to many of today’s blockbusters and the combination of well-conceived intertitles and Gottfried Huppertz’s score, render the lack of sound as more of an asset than an inconvenience. Lang’s assured direction (achieved through what many considered to be tyrannical methods) elevates Metropolis as high above the other films of the late 1920s as its real-world inspiration, Manhattan’s skyline, towered above the silhouettes of other great cities during the inter-war period.

Metropolis (Germany, 1927)

Cast: Gustav Frohlich, Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel, Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Fritz Rasp, Theodor Loos, Erwin Biswanger, Heinrich George

Home Release Date: 2020-01-19

Screenplay: Thea von Harbou, based on her novel

Cinematography: Karl Freund, Gunther Rittau, Walter Ruttmann

Music: Gottfried Huppertz

U.S. Distributor: Paramount Pictures

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Violence, Brief Nudity, Sexual Content)

Genre: Science Fiction

Subtitles: Silent Film with Intertitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- (There are no more better movies of Gustav Frohlich)

- (There are no more worst movies of Gustav Frohlich)

- (There are no more better movies of Brigitte Helm)

- (There are no more worst movies of Brigitte Helm)

- (There are no more better movies of Alfred Abel)

- (There are no more worst movies of Alfred Abel)

Comments