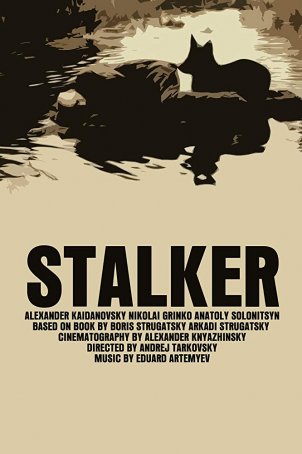

Stalker (USSR, 1979)

April 27, 2019

There’s little doubt that the films of Andrei Tarkovsky represent an acquired taste. The celebrated Soviet filmmaker’s style is so antithetical to modern cinema that it requires patience and stamina to become involved in any of his pictures – something not aided by seeing his creations on the small screen. (Bigger screens aid the process of immersion.) While there’s nothing inherently wrong with slow pacing, Tarkovsky takes this to extremes. At times, he seems almost to be daring his audience to stay awake – and it requires concentration to do so. His movies proceed glacially and, although one can argue that there’s power in such a gradual, deliberate progression, it makes for a daunting experience. He’s also wont to slip into pretentiousness with philosophizing that often sounds deeper than it is. His observations about the human condition, although invariably accurate, are often unsurprising. I don’t think I’ve ever watched a Tarkovsky movie and come away thinking I was exposed to a new idea. Stalker is a perfect example. A core theme is that one’s innermost desire may not be what one thinks it is and that one may be better off not achieving it, even when it’s close at hand. Or, as it has been more succinctly described elsewhere: “Be careful what you wish for, you may get it.”

I no longer scratch my head when I see something like Stalker praised as one of the best films ever made. It is masterfully done, contains some haunting images, and has a difficult-to-pinpoint mesmerism in the way it progresses. Once it gets you (which, for some, may never happen), it will hold you like a fly trapped in amber. But elevating it to the highest level of cinema represents the embrace of a sophisticated perspective of motion pictures that I find elitist and exclusionary. Reportedly, when the Soviet State Committee for Cinematography suggested that Stalker could be improved by being faster, Tarkovsky responded, “I am only interested in the views of two people: one is called Bresson and one called Bergman.”

Technically, Stalker

is science fiction, but there’s nothing

beyond a central idea that one would ordinarily associate with the genre. For

that reason, the classification feels like a marketing hook instead of a

legitimate description. Stalker is

more about philosophy than sci-fi. It’s about people pondering what they want,

what would make them happy, whether happiness is possible for human beings, and

what price a person might be willing to pay for it. The screenplay is loosely

based on the novel Roadside Picnic by

Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, although only a few basic ideas from the book made

it to the screen. Tarkovsky, as was usual for him, reworked the story to suit

his vision.

Technically, Stalker

is science fiction, but there’s nothing

beyond a central idea that one would ordinarily associate with the genre. For

that reason, the classification feels like a marketing hook instead of a

legitimate description. Stalker is

more about philosophy than sci-fi. It’s about people pondering what they want,

what would make them happy, whether happiness is possible for human beings, and

what price a person might be willing to pay for it. The screenplay is loosely

based on the novel Roadside Picnic by

Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, although only a few basic ideas from the book made

it to the screen. Tarkovsky, as was usual for him, reworked the story to suit

his vision.

“The Zone,” as it is called, is an area where something once happened – possibly an alien landing. Within the Zone, the normal laws of physics and reality no longer apply. At the center of the Zone is a Room which offers the fulfillment of the “greatest inner desire” of all who enter. The Zone has been quarantined by a fearful government but a select group of men, called “stalkers,” offer to guide people to the Room, getting them past the military blockade of the Zone and divining the ever-changing path to the Room. In Stalker, the title character is played by Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy. His clients are an unnamed Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn) and an equally unnamed Professor (Nikolay Grinko). Grim, cynical, and serious men, these two appear to have lost their humanity and are looking to regain it. The Writer claims he is on a quest for inspiration. The Professor hopes to win a Nobel Prize for performing a scientific analysis of the Zone. But, as the Stalker cautions, stated desires don’t necessarily represent innermost ones.

The trip to the Room is arduous. It begins outside the Zone.

For this segment of Stalker,

Tarkovsky elected to film in a monochromatic brown that makes everything appear

dirty and disused. It emphasizes the glumness and hopelessness of the normal

world. Once the characters evade the government blockade and enter the Zone,

Tarkovsky switches to conventional color. Although the Zone isn’t large, there

are traps everywhere so movement must necessarily be slow and circuitous. The

Writer in particular chafes at the indirect route while the Professor does as

instructed – except on the occasion when he leaves behind his backpack and returns

for it.

The trip to the Room is arduous. It begins outside the Zone.

For this segment of Stalker,

Tarkovsky elected to film in a monochromatic brown that makes everything appear

dirty and disused. It emphasizes the glumness and hopelessness of the normal

world. Once the characters evade the government blockade and enter the Zone,

Tarkovsky switches to conventional color. Although the Zone isn’t large, there

are traps everywhere so movement must necessarily be slow and circuitous. The

Writer in particular chafes at the indirect route while the Professor does as

instructed – except on the occasion when he leaves behind his backpack and returns

for it.

Stalker is not without moments of tension. Although the film begins sedately, Tarkovsky ramps up the suspense as the three trespassers use a train’s passage to gain entrance to the Zone. Although the journey through the wilderness leading to the Room is supposed to put the viewer on edge, I found this segment to be dull and drawn-out. The altercation outside the Room, in which motivations are revealed and hostilities come into the open, represents the film’s most dynamic, involving sequence. It effectively concludes the stories of the Writer and the Professor. An epilogue, like the prologue, focuses on the Stalker and his family. (He has a wife and a little girl.)

One of the most striking aspects of Stalker is the imagery Tarkovsky presents. Although the Zone may offer wish-fulfillment, it looks nothing like the paradise one might expect from such a magical place. Instead, it’s an industrial ruin, a monument to Soviet Cold War manufacturing excess. Although there are places where nature has begun to reclaim the land, most of the Zone is an ugly reflection of consumption and environmental rape. The water is poisoned (in actuality as well as on film – several crewmembers believe Tarkovsky’s terminal cancer resulted from his prolonged exposure to toxic elements) and everything looks unhealthy. The majority of the film was shot on location in and around deserted hydro power plants and chemical factories in Estonia. No verbal commentary is made about the film’s surroundings – none is needed; the images are sufficiently eloquent. Tarkovsky’s long takes (many lasting more than a minute) emphasize the desecration.

The version of Stalker

released in 1980 (which is currently available on home video) is

technically a remake. Tarkovsky initially made the film in 1977 but, as a result

of a processing error, the entire location shoot was lost. Committed to the

project, the director re-shot the entire thing using a new shooting script.

Sources vary about how close the iterations of Stalker were to one another. Some claim the differences were minor.

Others state the entire plot was reworked. The cinematographer for the 1977 Stalker, Georgy Rerberg, was fired by

Tarkovsky and replaced by Aleksandr Knyazhinskiy.

The version of Stalker

released in 1980 (which is currently available on home video) is

technically a remake. Tarkovsky initially made the film in 1977 but, as a result

of a processing error, the entire location shoot was lost. Committed to the

project, the director re-shot the entire thing using a new shooting script.

Sources vary about how close the iterations of Stalker were to one another. Some claim the differences were minor.

Others state the entire plot was reworked. The cinematographer for the 1977 Stalker, Georgy Rerberg, was fired by

Tarkovsky and replaced by Aleksandr Knyazhinskiy.

Although Stalker is neither as powerful nor as compelling as Tarkovsky’s best-known work, Solaris, it has exerted an influence on many subsequent “serious” science fiction films, most notably Alex Garland’s recent Annihilation, which borrows elements wholesale. Along with Solaris and Andrei Rublev (both of which are more accessible), Stalker remains one of Tarkovsky’s best-known and most revered productions. It is by no means an “easy” movie with its somnambulant pace being a significant drawback. However, the movie has qualities that make it hard to forget and, on that basis alone, it is recommended viewing material for anyone serious about film.

Stalker (USSR, 1979)

Cast: Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy, Anatoliy Solonitsyn, Nikolay Grinko

Home Release Date: 2019-04-27

Screenplay: Arkadiy Strugatskiy & Boris Strugatskiy

Cinematography: Aleksandr Knyazhinskiy

Music: Eduard Artemev

U.S. Distributor: Media Transactions

U.S. Release Date: 1982-10-20

MPAA Rating: "NR"

Genre: Science Fiction

Subtitles: In Russian with subtitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- (There are no more better movies of Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy)

- (There are no more worst movies of Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy)

- Andrei Rublev (1971)

- (There are no more better movies of Anatoliy Solonitsyn)

- (There are no more worst movies of Anatoliy Solonitsyn)

- (There are no more better movies of Nikolay Grinko)

- (There are no more worst movies of Nikolay Grinko)

Comments