Full Metal Jacket (United Kingdom/United States, 1987)

November 19, 2017

There be Spoilers! here.

Over the space of a decade beginning with Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Apocalypse Now, no fewer than five influential directors made films about the Vietnam War. Four of those were clustered during the late 1980s: Oliver Stone’s Platoon, John Irvin’s Hamburger Hill, Brian De Palma’s Casualties of War, and Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Of that quartet, Platoon and Full Metal Jacket have best stood the test of time. Although Full Metal Jacket is not generally regarded as being among Kubrick’s “A-list” films, it represents his fourth anti-war outing as a director (following 1953’s Fear and Desire, 1957’s Paths of Glory, and 1964’s Dr. Strangelove). Like many films looking back on the Vietnam War era from a “distance”, Full Metal Jacket examines the dehumanizing impact of military training and combat on the human mindset.

In adapting from Gustav Hasford’s novel, Kubrick cherry-picked (as he was wont to do) scenes and ideas that he thought worked while discarding those that didn’t meet his vision. The resulting screenplay has a two-act structure with the first part of the book expanded and the second and third segments conflated. In typical Kubrickian fashion, although the movie resembles the source material in a general sort of way, the specifics had been reshaped to suit the filmmaker’s intentions.

Full Metal Jacket

is oddly structured. It’s a two-episode story where the only connection between

the segments is the recurrence of some of the characters. The second act is

less a continuation of the first than a completely different story. The first part,

which functions as a Stateside extended prologue, consumes about 45 minutes of the

116-minute running time. The remaining hour-plus transports us to Vietnam at

the time of the Tet Offensive.

Full Metal Jacket

is oddly structured. It’s a two-episode story where the only connection between

the segments is the recurrence of some of the characters. The second act is

less a continuation of the first than a completely different story. The first part,

which functions as a Stateside extended prologue, consumes about 45 minutes of the

116-minute running time. The remaining hour-plus transports us to Vietnam at

the time of the Tet Offensive.

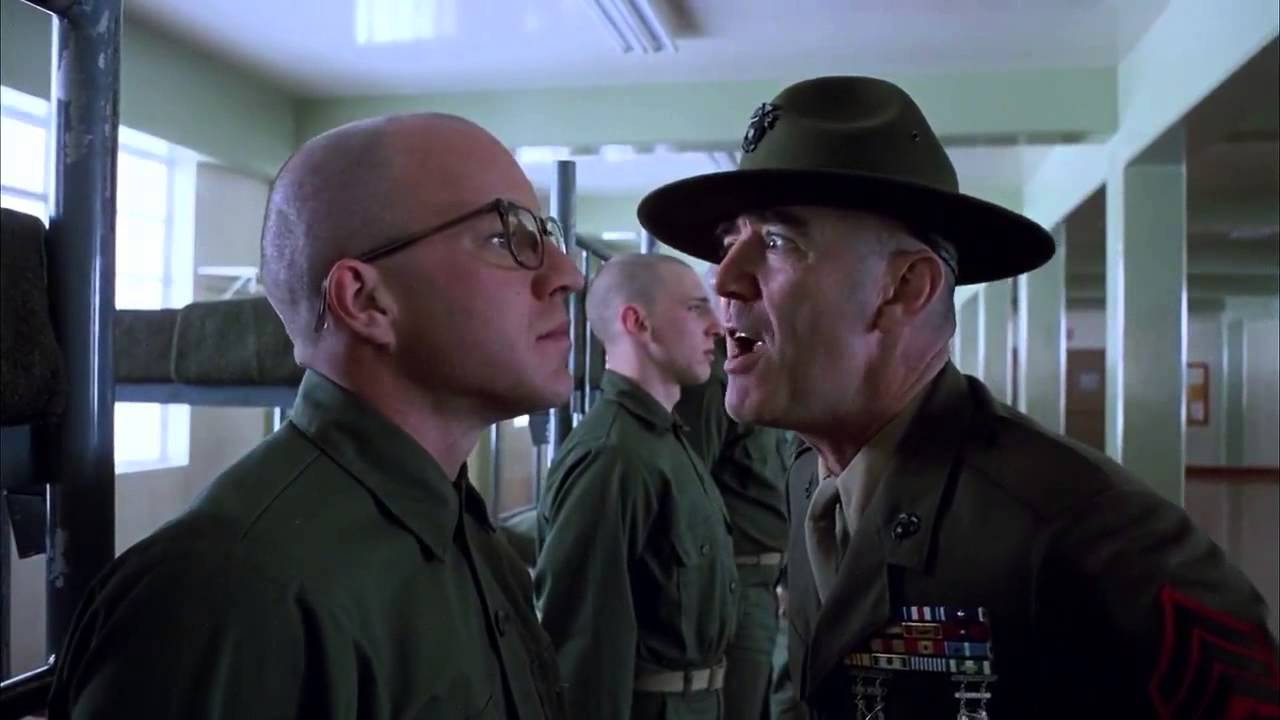

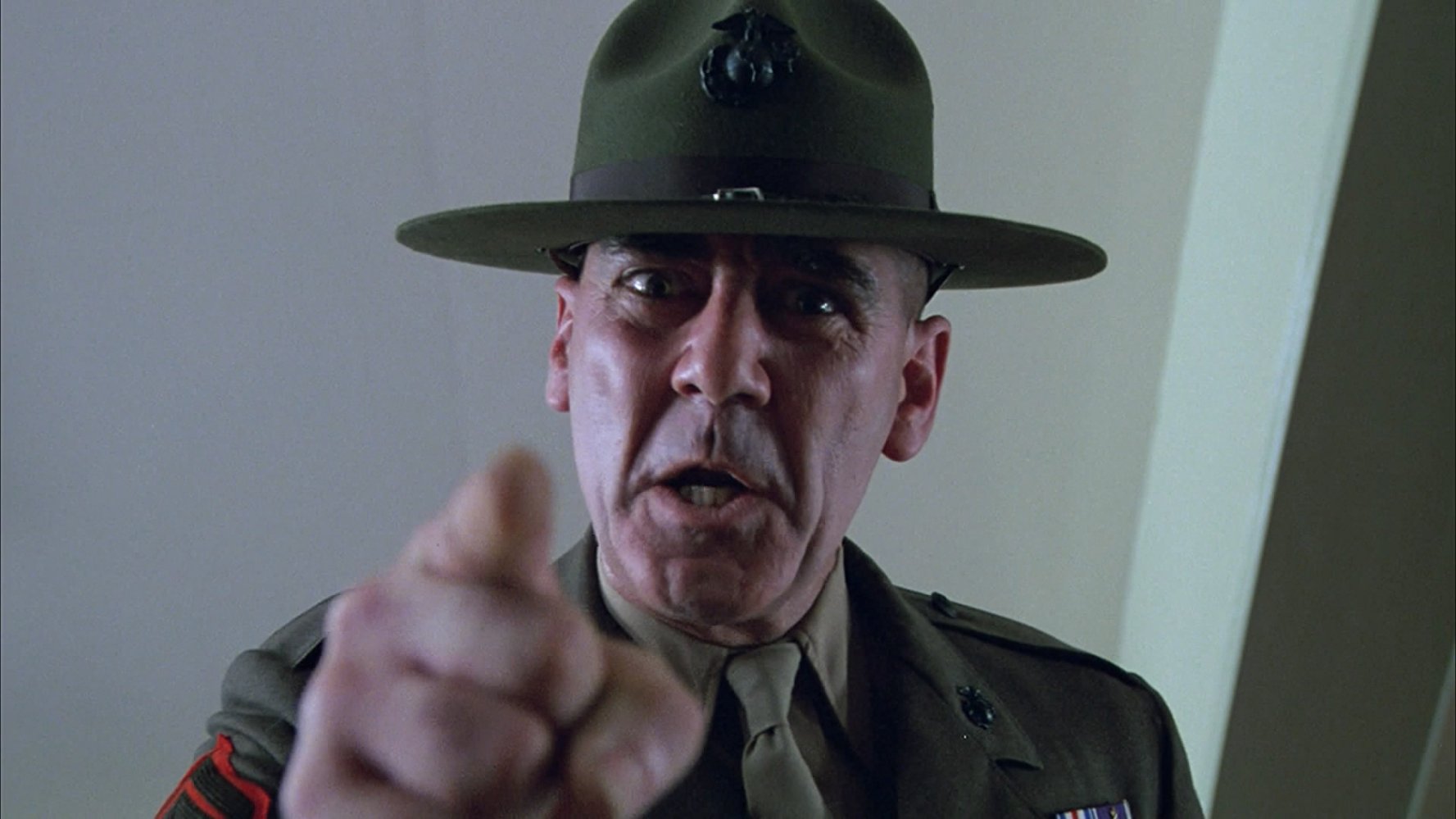

Full Metal Jacket opens with the arrival of a group of new Marine trainees at Parris Island, South Carolina. They include three principals: James Davis, who goes by “Joker” (Matthew Modine); Robert “Cowboy” Evans (Arliss Howard); and Leonard Lawrence (Vince D’Onofrio), who earns the derisive nickname of “Gomer Pyle” from Drill Instructor Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). Hartman’s style is uncompromisingly harsh. He sees it as his job to transform undisciplined boys into cold killers. He is ruthless, using profanity-laced tirades and physical abuse to achieve his methods. Some recruits thrive under him but others, like Pyle, become unbalanced. The results are tragic but not entirely unpredictable.

Act Two skips ahead an unspecified number of months to early

1968. Joker is a war correspondent stationed in South Vietnam. Along with

photographer Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard), he is sent to Phu Bai to

rendezvous with the Lusthog Squad, of which Cowboy is a member. Joker and

Rafterman are with the squad during the Battle of Hue. Shortly thereafter, the

squad leader is killed by a booby trap and Cowboy is forced to take command.

They come under sniper fire and dissention about how to handle casualties

results in a breakdown of order. The squad’s machine gunner, Animal Mother

(Adam Baldwin), acts rashly and, although his actions locate the sniper, they

result in the death of a “friendly.”

Act Two skips ahead an unspecified number of months to early

1968. Joker is a war correspondent stationed in South Vietnam. Along with

photographer Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard), he is sent to Phu Bai to

rendezvous with the Lusthog Squad, of which Cowboy is a member. Joker and

Rafterman are with the squad during the Battle of Hue. Shortly thereafter, the

squad leader is killed by a booby trap and Cowboy is forced to take command.

They come under sniper fire and dissention about how to handle casualties

results in a breakdown of order. The squad’s machine gunner, Animal Mother

(Adam Baldwin), acts rashly and, although his actions locate the sniper, they

result in the death of a “friendly.”

If there’s an obvious criticism of Full Metal Jacket, it relates to the imbalance between acts. The first, shorter episode is the more compelling and powerful segment. It features a tour de force performance by R. Lee Ermey and an introspective portrayal by Vincent D’Onofrio. Neither of those characters is around for the rest of the film (their stories having been concluded before the 45-minute mark) and the movie suffers as a result. There’s nothing wrong with the second episode – in fact, it offers a gut-wrenching portrait of the chaos of the Vietnam War – but it feels anti-climactic. At times, it’s difficult to shake the feeling that something is missing, and that “something” is the energy and passion that Ermey brings to the early scenes.

Ermey, a real Marine drill instructor before leaving the corps and starting work as an actor, had been hired by Kubrick to serve as a technical advisor. He so impressed the director during an audition that Kubrick not only hired him to play Hartman but allowed him to improvise up to 50% of his dialogue. It’s mystifying that Ermey, who should have been a contender for the Best Supporting Actor Oscar in 1988, wasn’t even nominated, although he was at least acknowledged by the Golden Globes. (Note: Sean Connery won the Oscar for The Untouchables and, since that was in the nature of a “career achievement”, no one was going to beat him. However, Ermey’s being denied a nomination remains one of the Oscars’ all-time most egregious snubs.)

The lead, originally intended to be played by Anthony

Michael Hall and then by Bruce Willis, was eventually given to Matthew Modine.

Modine’s low-key style works in this context. Joker, as a journalist, was more

of an observer than a man of action and so his ability to fade into the

background and allow other actors to take center stage in various scenes is

effective in that context. Unfortunately, it limits the power of the climactic

moment because we don’t identify strongly enough with the main character for it

to deliver the intended gut-punch.

The lead, originally intended to be played by Anthony

Michael Hall and then by Bruce Willis, was eventually given to Matthew Modine.

Modine’s low-key style works in this context. Joker, as a journalist, was more

of an observer than a man of action and so his ability to fade into the

background and allow other actors to take center stage in various scenes is

effective in that context. Unfortunately, it limits the power of the climactic

moment because we don’t identify strongly enough with the main character for it

to deliver the intended gut-punch.

One memorable post-Ermey sequence has nothing to do with war but with establishing the culture into which American G.I.s found themselves during the war. The first thing we see after the final shot of the bloody bathroom tableau is a street corner in Vietnam. Cue Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walking” as actress/model Papillon Soo Soo sashays across the street, approaches Modine and speaks words that have since become iconic (thanks in part to 2 Live Crew): “Me so horny. Me love you long time.” It’s played for laughs, and isn’t the only scene with an undercurrent of humor. Some of the basic training scenes also have a comedic edge.

Full Metal Jacket

features Kubrick’s legendary obsession about detail. The movie looks impeccable

and the photography emphasizes the claustrophobia of the barracks during the

early scenes and the dangers of wide-open spaces later in the film. The way

Kubrick frames Ermey as he prowls around the barracks is unsettling. These are

mostly long takes that capture the cavernous room, with the camera sometimes

following Ermey as he strides between the rows of men. The discordant score,

provided by “Abigail Mead” (actually Kubrick’s daughter, Vivian), is the

perfect accompaniment.

Full Metal Jacket

features Kubrick’s legendary obsession about detail. The movie looks impeccable

and the photography emphasizes the claustrophobia of the barracks during the

early scenes and the dangers of wide-open spaces later in the film. The way

Kubrick frames Ermey as he prowls around the barracks is unsettling. These are

mostly long takes that capture the cavernous room, with the camera sometimes

following Ermey as he strides between the rows of men. The discordant score,

provided by “Abigail Mead” (actually Kubrick’s daughter, Vivian), is the

perfect accompaniment.

Of all the ‘80s-era Vietnam War films, Full Metal Jacket is arguably the least overtly critical about the conflict. The movie isn’t political. This was by intent; Kubrick didn’t want to regurgitate Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter, or Platoon. He believed that it was enough to show war, unglamorized, for what it was, and that people would understand. At the time, some critics perceived this as another Kubrick masterpiece while others (notably Roger Ebert) felt it was too scattershot to achieve its aims. I think those in the former camp rated the movie too highly. Perhaps the name “Kubrick” skewed their impressions. Although the astonishing first 45 minutes are on par with anything the director had previously accomplished, the second half of the film falls short of greatness.

Platoon remains the most searing of all the Vietnam War films. After that, I’d argue that Full Metal Jacket is as worthy as any of the other contenders (including the overrated Apocalypse Now) for second place. It has effectively stood the test of time. It’s as credible and effective today as it was on its release 20 years ago and its depictions of war and how men are molded by war have lost none of their power.

Full Metal Jacket (United Kingdom/United States, 1987)

Cast: Matthew Modine, Arliss Howard, R. Lee Ermey, Adam Baldwin, Vincent D’Onofrio, Kevyn Major Howard

Home Release Date: 2017-11-19

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick & Michael Herr & Gustav Hasford, based on “The Short-Timers” by Gustav Hasford

Cinematography: Douglas Milsome

Music: Abigail Mead

U.S. Distributor: Warner Brothers

U.S. Release Date: 1987-07-10

MPAA Rating: "R" (Violence, Profanity, Sexual Content)

Genre: War/Drama

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- (There are no more better movies of this genre)

- Short Cuts (1993)

- Sicario: Day of the Soldado (2018)

- (There are no more better movies of Matthew Modine)

- Mank (2020)

- Killer, The (2023)

- (There are no more better movies of Arliss Howard)

- Lost World, The: Jurassic Park 2 (1997)

- (There are no more worst movies of Arliss Howard)

- Dead Man Walking (1996)

- Saving Silverman (2001)

- (There are no more better movies of R. Lee Ermey)

- Man of the House (2005)

- (There are no more worst movies of R. Lee Ermey)

Comments