Playtime (France, 1967)

August 18, 2019

Playtime, the 1967 comedy from acclaimed French director Jacques Tati, is an odd film (even coming out of a tradition of filmmaking that prided itself on defying conventions and breaking barriers). With no real plot and little in the way of character definition, Playtime exists as a two-hour exploration of Tati’s thesis about the dehumanizing implications of modern society. Images and sound are critical elements of this excursion into the absurd which draws inspiration from Chaplin (Modern Times in particular) and helps till the fertile ground that would sprout Monty Python. (Brazil, made by Python alum Terry Gilliam, owes more than a passing debt to Playtime.)

There are two distinct ways to watch Playtime. It can be viewed like any other movie – as a progression of scenes that, strung together from start to finish, create something like a narrative. Those who approach Playtime from the perspective are likely to find it occasionally intriguing, sometimes pointless, and often frustrating. Tati isn’t interested in conventional pacing and, as a result, many sequences extend for longer than seems necessary, transforming what might have been a breezy 90-minute film into a grind.

The other way to engage with Playtime is to do it in a more scholarly way. Careful, thoughtful

examination of each scene reveals a meticulous attention to detail and a more

deeply-rooted sense of humor than is evident from a cursory viewing. Playtime rewards multiple showings but

it demands concentration. It’s possible to get a sense of what Tati intended by

watching the movie a single time but the production is designed as more than

light, disposable entertainment.

The other way to engage with Playtime is to do it in a more scholarly way. Careful, thoughtful

examination of each scene reveals a meticulous attention to detail and a more

deeply-rooted sense of humor than is evident from a cursory viewing. Playtime rewards multiple showings but

it demands concentration. It’s possible to get a sense of what Tati intended by

watching the movie a single time but the production is designed as more than

light, disposable entertainment.

Many movies follow the time-honored “three-act” structure, but there’s nothing like that in Playtime. Instead, there are six distinct set pieces, some of which are longer than others, but all of which illustrate some aspect of how advances in technology have fractured human interaction and created a distance that only extreme events can break down. The story (to the extent there can be said to be a story) moves back and forth between the character of Monsieur Hulot (Jacques Tati), the protagonist of several of Tati’s other films, and Barbara (Barbara Dennek), an American in Paris.

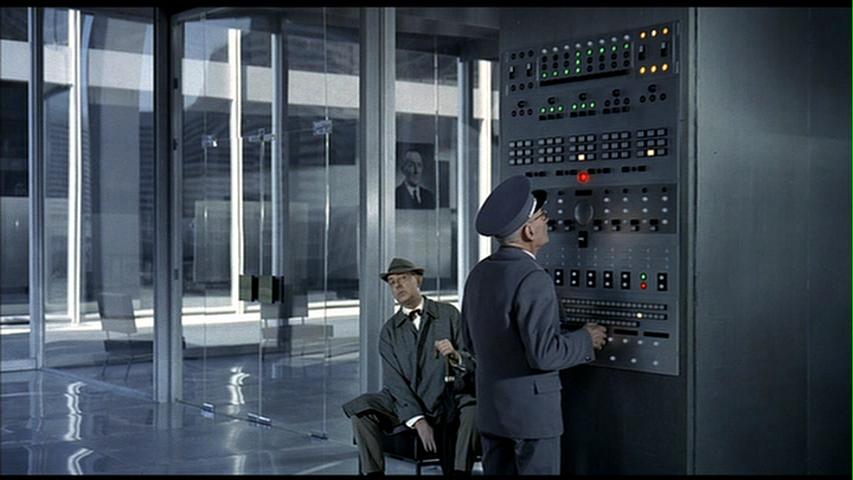

The first scene transpires in a large, impersonal airport

where M. Hulot is waiting to board a plane to Paris. He is joined by a group of

noisy American tourists. Barbara is among them. The scene then shifts to an

office building in Paris, where Hulot has an appointment with a manager (the

reason for the appointment is never made clear). After being admitted, Hulot

becomes lost in the labyrinth of glass doors and walls while the man he was

supposed to meet searches for him. At a trade exhibition, Hulot, Barbara, and

the other Americans are given a peek at the latest gadgets, including a door

that closes silently and a broom with headlights. Barbara attempts to

photograph a florist whose stall looks old-fashioned but “modern” people keep

getting in the way. Later in the evening, Hulot meets an old friend who invites

him into his house for a drink and to watch some TV. This entire sequence is

depicted from outside the plate-glass windows that form the front walls of

series of apartments. The camera puts the viewer in the position of a voyeur

(not unlike what Hitchcock achieved in Rear Window).

The first scene transpires in a large, impersonal airport

where M. Hulot is waiting to board a plane to Paris. He is joined by a group of

noisy American tourists. Barbara is among them. The scene then shifts to an

office building in Paris, where Hulot has an appointment with a manager (the

reason for the appointment is never made clear). After being admitted, Hulot

becomes lost in the labyrinth of glass doors and walls while the man he was

supposed to meet searches for him. At a trade exhibition, Hulot, Barbara, and

the other Americans are given a peek at the latest gadgets, including a door

that closes silently and a broom with headlights. Barbara attempts to

photograph a florist whose stall looks old-fashioned but “modern” people keep

getting in the way. Later in the evening, Hulot meets an old friend who invites

him into his house for a drink and to watch some TV. This entire sequence is

depicted from outside the plate-glass windows that form the front walls of

series of apartments. The camera puts the viewer in the position of a voyeur

(not unlike what Hitchcock achieved in Rear Window).

Much of the film’s second half transpires in The Royal Garden, a restaurant/night club that is experiencing opening night problems. Construction workers are still feverishly toiling as customers are seated. The movie spends an extraordinarily long time exploring the various gaffes and blunders that compromise the bungled opening. Hulot and Barbara eventually arrive and each becomes involved in minor subplots that evolve against the backdrop of electrical short-circuits, blown fuses, and collapsing masonry. By morning, Barbara is ready to leave the city and, wearing a scarf purchased for her by Hulot, she boards a bus that becomes trapped in a traffic circle, going around and around like a carousel.

Fans of Tati’s more conventional previous films, Mon Oncle and M. Hulot’s Holiday, will appreciate the return of the director’s

beloved character, but this isn’t really a “Hulot film.” His presence is

largely superfluous and he could have been replaced by any good-hearted,

unsophisticated person. His cluelessness when it comes to technology is his

sole defining characteristic. Barbara, for her part, is a romantic – she is

disappointed by Paris, which is defined more by steel-and-glass skyscrapers

than the Eiffel Tower. The past, it seems, has been swept away in a wave of

modernism.

Fans of Tati’s more conventional previous films, Mon Oncle and M. Hulot’s Holiday, will appreciate the return of the director’s

beloved character, but this isn’t really a “Hulot film.” His presence is

largely superfluous and he could have been replaced by any good-hearted,

unsophisticated person. His cluelessness when it comes to technology is his

sole defining characteristic. Barbara, for her part, is a romantic – she is

disappointed by Paris, which is defined more by steel-and-glass skyscrapers

than the Eiffel Tower. The past, it seems, has been swept away in a wave of

modernism.

Tati’s message about the isolating influence of advancing technology rings true today. Paradoxically, while technology has made the world a smaller and more intimate place, it has created barriers between people – invisible walls that grow larger and are better fortified with every new invention. Tati, if he was still alive (he died in 1982), might look at today’s worldwide social climate and shake his head knowingly. However, his view of what constitutes “modern” is quaint. Tati might have been a great filmmaker but he wasn’t the best prognosticator when it came to imagining technological advances. (Although, at least in some cases, these are intended satirically.)

Images and ambient sound are critical to the director’s

intent. There isn’t much dialogue and what there is, is inconsequential. (This,

and the fact that some of the dialogue is in English, makes the need to read

subtitles minimal.) Tati uses sound to emphasize the atmosphere: the echo of

footsteps in the airport, the hum of florescent lighting in the office

building, the chaos of the nightclub, and the silence – punctuated only by

“street sounds” – of looking through the apartment windows, where things can be

seen but not heard. Tati’s cameras never get too close to the characters,

preferring wide and mid-range shots. This accentuates the distance and lack of

intimacy.

Images and ambient sound are critical to the director’s

intent. There isn’t much dialogue and what there is, is inconsequential. (This,

and the fact that some of the dialogue is in English, makes the need to read

subtitles minimal.) Tati uses sound to emphasize the atmosphere: the echo of

footsteps in the airport, the hum of florescent lighting in the office

building, the chaos of the nightclub, and the silence – punctuated only by

“street sounds” – of looking through the apartment windows, where things can be

seen but not heard. Tati’s cameras never get too close to the characters,

preferring wide and mid-range shots. This accentuates the distance and lack of

intimacy.

Playtime is a comedy but, as is often the case with more intellectual humor, the jokes are more likely to provoke smiles and chuckles that outright laughter. (I laughed aloud once during the entirety.) It’s a must-see for those with a penchant for droll, avant-garde cinema or anyone fascinated more by technique than narrative. For others, it’s more of a curiosity than a can’t-miss production – a film that may fascinate for a while before starting to seem repetitive and overlong.

Playtime (France, 1967)

Cast: Jacques Tati, Barbara Dennek

Home Release Date: 2019-08-18

Screenplay: Jacques Tati, Jacques Lagrange, Art Buchwald

Cinematography: Jean Badal, Andreas Winding

Music: Francis Lemarque

U.S. Distributor: Continental Distributing

- (There are no more better movies of Jacques Tati)

- (There are no more worst movies of Jacques Tati)

- (There are no more better movies of Barbara Dennek)

- (There are no more worst movies of Barbara Dennek)

Comments