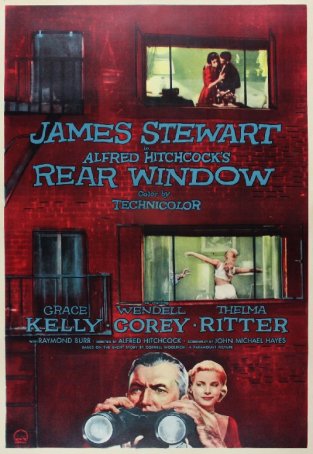

Rear Window (United States, 1954)

For several years now, the Alfred Hitchcock canon available in video stores has been incomplete. While most of the Master of Suspense's great works have been easily obtainable, Rear Window has been conspicuous by its absence. (This became a source of consternation when the Christopher Reeve remake aired on television and many would-be viewers wanted to watch or re-watch the original as a means of comparison.) The reason for the film's apparent vanishing act is that older video copies with their muddy, murky colors and telephone-quality sound were removed from the shelves while the film underwent a complete restoration. Supervised by the same team that resurrected Vertigo, this revived version of Rear Window is a positive triumph, restoring the film to the way it looked nearly fifty years ago and adding the bonus of digital sound.

Voyeurism is the act of observing the lives of others, often, but not always, for sexual gratification. It is a process through which people gain more satisfaction from viewing than living. There's a little bit of the voyeur in all of us - after all, going to a movie is nothing more than opening a window into the lives of others (fictional or real). It's a non-participatory experience that offers pleasure through the most simple of actions: watching. Therefore, it's no surprise that the motion picture industry has, from time to time, examined this aspect of the human experience. Movies about voyeurism come in all varieties - everything from serious studies to light, exploitative fare. The options are as varied as the activity.

One of the most engrossing, and, in its own way, groundbreaking, studies of voyeurism is Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window. The film is universally regarded as a classic, and a strong cadre of critics, scholars, and fans (myself included) considers this to be the director's best feature. Not only does the movie generate an intensely suspenseful and fascinating situation, but it develops a compelling and memorable character: L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart), a top-flight photographer who, as the result of an accident that left him in a leg cast, is confined to his upper-story Manhattan apartment. He amuses himself by gazing out his window at the building opposite, and builds pictures of each of the inhabitants from the glimpses he catches of their lives. Some of them, like "Miss Torso," a lithe young ballerina who capers around in various stages of dress, and "Miss Lonelyhearts," a forlorn spinster, keep their curtains wide open. Others, like a newlywed couple, pull down the blinds, leaving Jefferies to smile wryly as he guesses about their activities.

As Jefferies' days of confinement wear on, his fascination with his neighbors turns into an obsession. Their lives become more important than his. After all, they are vital and mobile; he is trapped and impotent. In his own words, he has had "six weeks sitting in a two-room apartment with nothing to do but look at the neighbors." He has a charming and gorgeous young girlfriend, Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly), but he is emotionally cool towards her, and their relationship is caught in the same stasis that paralyzes every other aspect of Jefferies' life. When he gropes for a reason why she wouldn't make a good wife, the only fault he can find is that she's "too perfect, too talented, too beautiful, and too sophisticated." Lisa may love him, but she is losing patience. Then, one day, Jefferies observes something that forces him to abandon his safe, cocooned role as a voyeur and become a participant. He sees - or thinks he sees - one of his neighbors, Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), commit a murder. When the police don't believe Jefferies, he is forced to take action without their help. Abetted by Lisa, he works to uncover evidence to prove that a crime was committed. However, with his mobility restricted, Jefferies can only watch through his rear window as Lisa puts herself in harm's way, and, when danger strikes, he is helpless to go to her rescue.

Few who have seen Rear Window do not consider it to be a top-notch thriller, and, even those who call another of Hichcock's masterpieces (Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho) his greatest, acknowledge the power and tension inherent in this one. It is an enduring classic that has been imitated and alluded to numerous times in the four-and-a-half decades since its debut, but nothing has equaled or surpassed it. In 1998, the picture was reinterpreted as a made-for-TV movie starring Christopher Reeve (his first major acting role since a riding accident left him paralyzed from the neck down). However, the lackluster quality of the remake has not affected the appeal of the original.

The idea of a casual voyeur seeing a murder is neither new nor unique, but the manner in which Hichcock presents it is singular. The setup is masterful, as we are given peeks into the rooms of many of Jefferies' unknowing neighbors: Miss Torso, Mrs. Lonleyhearts, Thorwald and his wife, a couple who beats the heat by sleeping on a fire escape, a songwriter, the newlyweds, and a local busybody. We view them in a variety of mundane activities: quarreling, gardening, exercising, talking, laughing, and crying. They are all minor threads in a much larger tapestry (and many of them never interact with Jefferies in any way, except as an object for him to watch), but we become curiously engaged by their personal stories.

The second phase of the movie is devoted to the murderous act. It is presented in such a way that, at least initially, we're not sure whether a crime has been committed or whether Jefferies is overreacting to a series of circumstances and coincidences. For the most part, we see only what Jefferies sees, but, in one critical scene that muddies the issue of whether or not there was a murder, Hitchcock throws in a red herring by allowing us to observe an incident that occurs while Jefferies is asleep.

It is during the third part of Rear Window, when Jefferies and Lisa team up to investigate the murder, that Hitchcock ratchets up the tension. Virtually the entire film is shown through Jefferies' window, including the sequence when Lisa slips into the killer's apartment. We view events from afar, and, like Jefferies, feel the weight of paralyzing powerlessness when Thorwald returns unexpectedly. Trapped in his room, there's no way Jefferies can warn Lisa or act to rescue her. All he (and we) can do is watch.

Hitchcock was always respected for stylistic experiments, and Rear Window is an example of an approach that worked brilliantly. With the exception of a few crucial shots during the climax, every scene in the movie is presented from within Jefferies' apartment. The camera stays with him, trapped within the confines of his room, never venturing outside, even when Lisa goes on her fact-finding mission. Events that occur outside of the window's view happen off-screen. The only time a character becomes real is when they appear in a window facing Jefferies' building or when they enter the room with him.

The acting is one of Rear Window's strengths. This is one of James Stewart's most impressive roles, primarily because of the limitations placed upon him. More than in any of his other films, he must act with his eyes, face, and voice. And Jefferies is not one of the morally upright, mild-mannered protagonists that Stewart became identified with. Instead, Jefferies is worldly, impatient, bad-tempered, and prone to bursts of anger. Some of the brilliant dialogue given to him by John Michael Hayes' script is biting. His frustration at being cooped up is palpable from the first frame, when Hitchcock's camera pans across the room, giving us a wealth of background information about Jefferies and his situation before a word is spoken.

Like a ray of pure sunshine, the luminous Grace Kelly lights up every scene she's in. Her character, Lisa, is a relentless optimist, and refuses to be deterred by Jefferies' moodiness. Like many of the heroines in Hitchcock movies, she is not especially well-developed, but Kelly's performance makes her hard not to like and admire. Would that we could all have significant others like her... Also appearing in Rear Window are the delightful Thelma Ritter as Jefferies' comical nurse, Stella; Wendell Corey as Tom Doyle, the police officer who investigates Jefferies' claims; and Raymond Burr as the possible killer.

Simply put, Rear Window is a great film, perhaps one of the finest ever committed to celluloid. All of the elements are perfect (or nearly so), including the acting, script, camerawork, music (by Franz Waxman), and, of course, direction. The brilliance of the movie is that, in addition to keeping viewers on the edges of their seats, it involves us in the lives of all of the characters, from Jefferies and Lisa to Miss Torso. There isn't a moment of waste in 113 minutes of screen time. This overdue restoration is greatly welcome, since it re-invigorates the look and sound of a timeless classic.

Rear Window (United States, 1954)

Cast: James Stewart, Grace Kelley, Wendell Corey, Thelma Ritter, Raymond Burr

Screenplay: John Michael Hayes based on a short story by Cornell Woolrich

Cinematography: Robert Burks

Music: Franz Waxman

U.S. Distributor: Universal Pictures

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "PG" (Violence)

Genre: THRILLER

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- Greatest Show on Earth, The (1952)

- (There are no more worst movies of James Stewart)

- (There are no more better movies of Grace Kelley)

- (There are no more worst movies of Grace Kelley)

- (There are no more better movies of Wendell Corey)

- (There are no more worst movies of Wendell Corey)

Comments