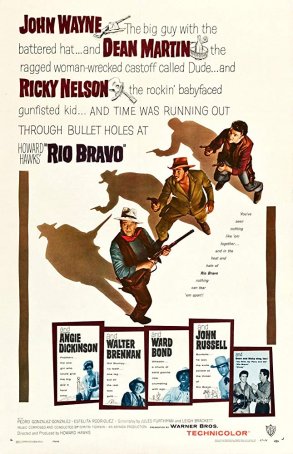

Rio Bravo (United States, 1959)

February 23, 2020

Rio Bravo, the acclaimed 1959 Howard Hawks Western, showcases a perfectly-cast John Wayne in the kind of role he defined during his four-plus decades of appearing before the camera. Although aspects of the movie have a dated feel when viewed long after its release, the core story – that of an upright sheriff and a small group of stalwarts standing against a gang of gun-toting criminals – remains solid. With an unnecessarily protracted running length of more than 140 minutes, Rio Bravo at times moves too slowly for its own good but the climax is as rousing as that of any Western made during the decade when the genre was at its peak.

As Westerns go, Rio Bravo neither attempts to nor succeeds in bringing much new to the table. The story unfolds in a 19th century Presidio County, Texas town where Sheriff John T. Chance (Wayne) has locked up outlaw Joe Burdette (Claude Akins) for murder. Chance is aided in his law-preserving duties by his deputies - Dude (Dean Martin), a one-time ace gunslinger-turned-drunk, and the aging, hobbled Stumpy (Walter Brennan), who runs the town’s jail. Upon hearing of his brother’s incarceration, gang-leader and landowner Nathan Burdette (John Russell) comes to pay a visit. He makes it clear that, one way or another, his brother will be walking out of jail. It’s up to Chance whether he wants to get out of the way or become a casualty.

Although most citizens of the town fade into the background

when the possibility of a shootout looks likely, Chance finds a few allies. An

old buddy of the sheriff’s, Pat Wheeler (Ward Bond), rides into town and offers

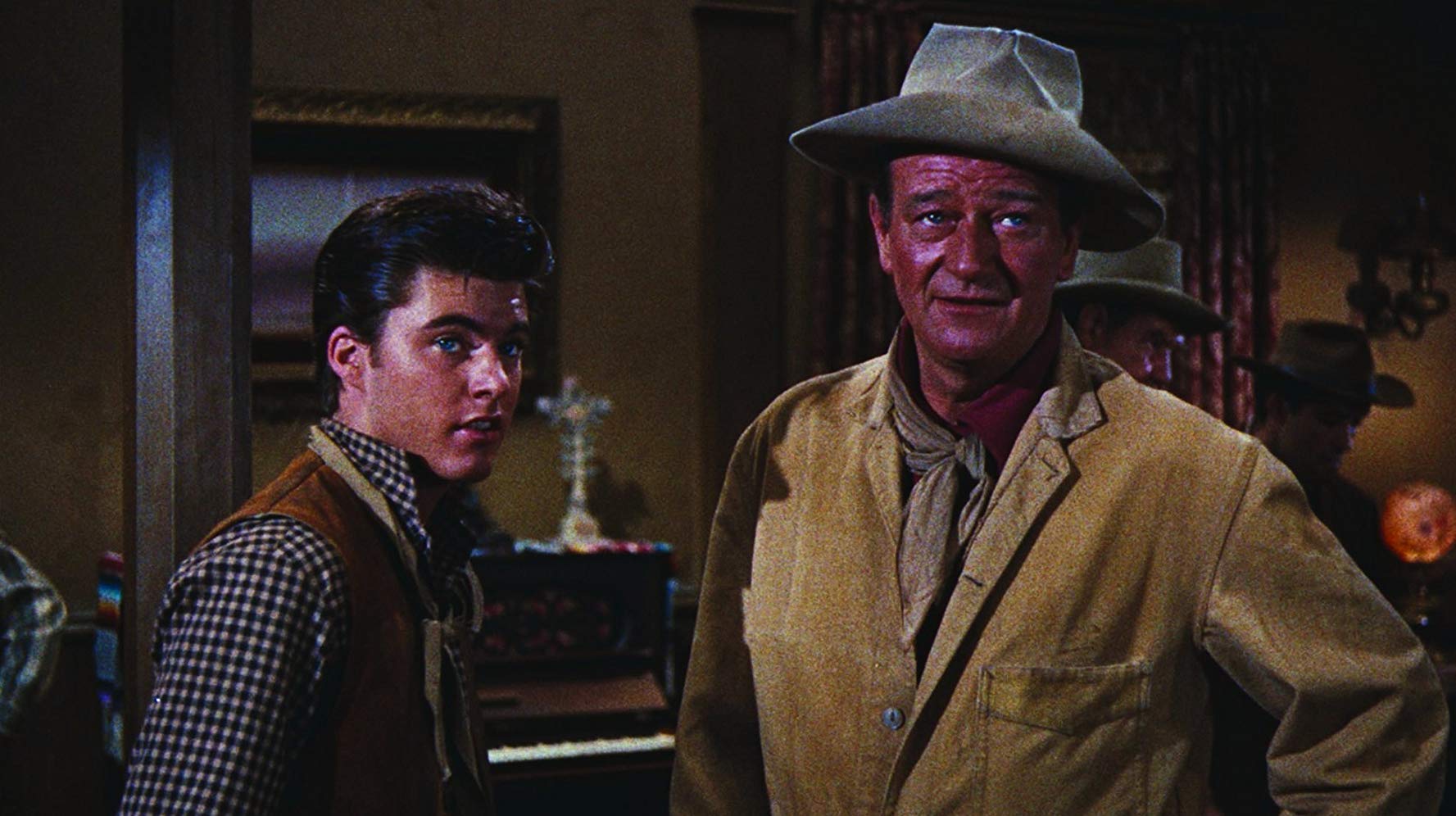

his help and that of his new protégé, Colorado Ryan (Ricky Nelson). When Pat is

shot dead by one of Burdette’s hired assassins, Chance takes it personally.

Another newcomer to Rio Bravo is Feathers (Angie Dickinson), a tough-talking,

poker-playing woman who is attracted to the taciturn lawman. The two flirt and

the flirting turns into a stronger attachment. Finally, the owner of the local

hotel, Carlos (Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez), throws in his lot with the sheriff.

Although most citizens of the town fade into the background

when the possibility of a shootout looks likely, Chance finds a few allies. An

old buddy of the sheriff’s, Pat Wheeler (Ward Bond), rides into town and offers

his help and that of his new protégé, Colorado Ryan (Ricky Nelson). When Pat is

shot dead by one of Burdette’s hired assassins, Chance takes it personally.

Another newcomer to Rio Bravo is Feathers (Angie Dickinson), a tough-talking,

poker-playing woman who is attracted to the taciturn lawman. The two flirt and

the flirting turns into a stronger attachment. Finally, the owner of the local

hotel, Carlos (Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez), throws in his lot with the sheriff.

Rio Bravo was a favorite of both Wayne and director Howard Hawks. In fact, they liked it so much that they collaborated on two quasi-remakes: 1966’s El Dorado and 1970’s Rio Lobo. Both of the later films again featured Wayne as the straight-as-an-arrow righteous man and followed the same general plot. Other than the star, however, none of the actors returned for the remakes. John Carpenter, an admitted fan of Rio Bravo, used elements of the story in both his 1976 thriller, Assault on Precinct 13, and his 2001 sci-fi outing, Ghosts of Mars.

With crooner Dean Martin and young singing sensation Ricky

Nelson in the cast, the temptation to include a couple of musical numbers (“My

Rifle, My Pony and Me” and “Cindy”) was apparently too great for Hawks to

resist. One might wish he had done so. The movie grinds to a halt for a what

amounts to a six-minute musical intermission on the night before the big

confrontation. In his four-star review of the film, Roger Ebert admits that the

songs may be out of place while confessing his affection for them. He writes:

“Does this scene feel airlifted in? Maybe, but I wouldn’t do without it.” For

me, the movie would have been considerably stronger without the unfortunate

interlude.

With crooner Dean Martin and young singing sensation Ricky

Nelson in the cast, the temptation to include a couple of musical numbers (“My

Rifle, My Pony and Me” and “Cindy”) was apparently too great for Hawks to

resist. One might wish he had done so. The movie grinds to a halt for a what

amounts to a six-minute musical intermission on the night before the big

confrontation. In his four-star review of the film, Roger Ebert admits that the

songs may be out of place while confessing his affection for them. He writes:

“Does this scene feel airlifted in? Maybe, but I wouldn’t do without it.” For

me, the movie would have been considerably stronger without the unfortunate

interlude.

It’s tempting to say that John Wayne is adhering to his typical John Wayne image and, although there’s some truth to that, it may be giving the actor too little credit. Wayne says a lot more with his body language than he does with his dialogue and Chance comes across as a deeper character than one might initially suppose. He is well matched by Angie Dickinson and, while no one is going to call the pair one of Hollywood’s great screen couples, there’s enough chemistry for us to ignore the nearly 25-year age gap. Dean Martin sometimes overacts and Ricky Nelson is often badly in need of acting lessons. The always delightful Walter Brennan provides effective comic relief.

It’s impossible to discuss Rio Bravo without bringing

up High Noon, in large part because the former film was made in part as

a repudiation of the 1952 production. Wayne was openly critical of the earlier

movie, going so far as to call it “Un-American.” It’s interesting that many of Rio

Bravo’s most ardent supporters (like Ebert) have voiced a dislike of High Noon. More than a half-century later, both productions are generally

regarded as classics.

It’s impossible to discuss Rio Bravo without bringing

up High Noon, in large part because the former film was made in part as

a repudiation of the 1952 production. Wayne was openly critical of the earlier

movie, going so far as to call it “Un-American.” It’s interesting that many of Rio

Bravo’s most ardent supporters (like Ebert) have voiced a dislike of High Noon. More than a half-century later, both productions are generally

regarded as classics.

Fifteen years prior to making Rio Bravo, Hawks famously directed Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not, a movie that may offer the best-known example of real-life chemistry burning up the screen. Hawks was also behind the camera when the two were reunited in The Big Sleep. Similarities between the Wayne/Dickinson relationship and that of Bogart and Bacall are intentional, right down to some of the dialogue. The difference was, of course, that there was no off-screen connection in Rio Bravo and, as a result, there’s more smoke than fire.

Rio Bravo is as much a cornerstone of Wayne’s legacy as Stagecoach, The Searchers, Red River, and True Grit. It came near the apex of his popularity and became one of his best-loved outings. Viewed through the lens of history, Rio Bravo has lost some of its luster and, while the action sequences remain entertaining and the build-up to the final confrontation is fraught with suspense, the movie as a whole tends more toward the “generic Western” than Wayne’s other defining films.

Rio Bravo (United States, 1959)

Cast: John Wayne, Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, Angie Dickinson, Walter Brennan, Ward Bond, John Russell, Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez, Claude Akins

Home Release Date: 2020-02-23

Screenplay: Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett, based on the short story by B.H. McCampbell

Cinematography: Russell Harlan

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

U.S. Distributor: Warner Brothers

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Violence)

Genre: Western

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The (1962)

- Quiet Man, The (1969)

- (There are no more better movies of John Wayne)

- (There are no more worst movies of John Wayne)

- (There are no more better movies of Dean Martin)

- (There are no more worst movies of Dean Martin)

- (There are no more better movies of Ricky Nelson)

- (There are no more worst movies of Ricky Nelson)

Comments