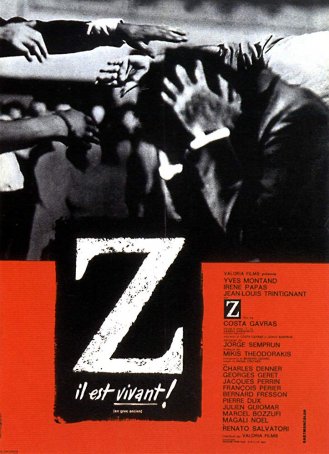

Z (Algeria/France, 1969)

February 16, 2019

It’s rare that a movie can shock with its timelessness, but Z is such a film – no less relevant today than when Costa-Gavras made it in 1969. In his contemporaneous review, Roger Ebert said the following: “It is a film of our time. It is about how even moral victories are corrupted.” The following thoughts emerged from my pen in 2006 when I first wrote about the production: “Despite having been made nearly four decades ago, the themes are as relevant today as they were in 1969, even though the world has undergone many changes. The core argument - how fascist elements, claiming to be ‘patriotic,’ can undermine a democracy from within by seeking to quell ‘unpopular’ viewpoints - is a danger that must be guarded against as diligently in 2006 as when Z first opened.” Considering today’s political climate, Z is proof that some things don’t change as quickly as we might hope and that certain aspects of human nature will strive to hold back progress.

Z (the title means “He Lives”) is loosely

based on facts, although Costa-Gavras elected not to use the names of the

actual participants when he made the film. By using generic designators like

“The Deputy”, “The General”, “The Judge”, and so forth, he is able to move the

film out of a specific time and place and give it a universal setting. However,

there’s no mistaking the historical markers that inspired it. On May 22, 1963,

Greek opposition leader Gregorios Lambrakis was assassinated in an incident

made to look like a traffic accident. The government appointed an investigator

to examine events, expecting him to rubber stamp the official story. But

Christos Sartzetakis was a man of principal and he uncovered evidence of a

conspiracy that involved an ultra-right wing organization, government

officials, and high-ranking police officers.

Z (the title means “He Lives”) is loosely

based on facts, although Costa-Gavras elected not to use the names of the

actual participants when he made the film. By using generic designators like

“The Deputy”, “The General”, “The Judge”, and so forth, he is able to move the

film out of a specific time and place and give it a universal setting. However,

there’s no mistaking the historical markers that inspired it. On May 22, 1963,

Greek opposition leader Gregorios Lambrakis was assassinated in an incident

made to look like a traffic accident. The government appointed an investigator

to examine events, expecting him to rubber stamp the official story. But

Christos Sartzetakis was a man of principal and he uncovered evidence of a

conspiracy that involved an ultra-right wing organization, government

officials, and high-ranking police officers.

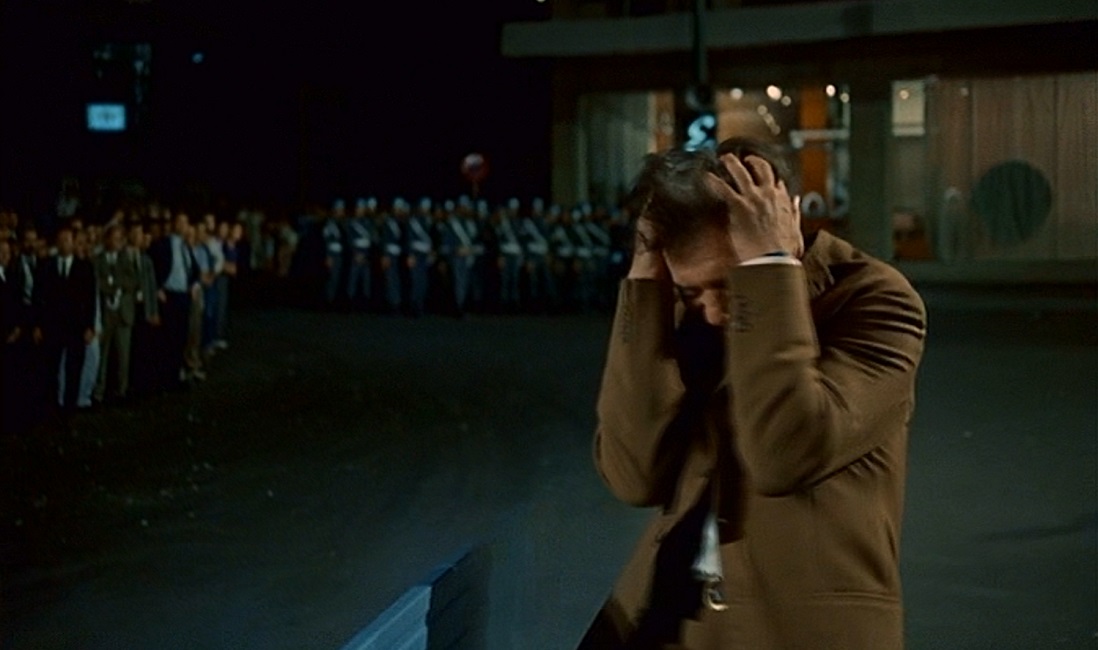

When Z ends, it looks like the forces for truth and justice will triumph…until we get to the epilogue, which echoes the historical facts from Greece where a 1967 coup resulted in a military takeover. The criminals indicted by Sartzetakis were “rehabilitated” and those who exposed the conspiracy were killed or jailed (including Sartzetakis). Eventually, Greece recovered and was set back on a path to democracy following the 1974 toppling of the dictatorship. Sartzetakis would eventually be elected President and served from 1985 until 1990. But all those “good” things represent footnotes to the bleak story told in Z.

The movie is effectively divided into two sections. The first focuses

on the assassination of The Deputy (Yves

Montand) and the second details the investigation of The Judge (Jean-Louis

Trintignant) into what is initially known as “the incident” but is eventually

called “the murder.” Although Costa-Gavras never hides the film’s politics,

this is presented as a thriller with rising tension and even a car chase (as an

attempt is made on a witness’ life). Z’s

theme is that of the lone good man standing against a corrupt system but, in a

brutally realistic twist on the usual triumphant ending, the movie turns the

tables in the closing minutes. The seemingly inevitable victory is stolen away,

leaving behind emptiness, anger, and a sense that this is how the real world works. We see with double vision,

looking equally at events in the 1960s and today – whenever “today” is. (My

guess is that whenever you read this, whether it’s 2018, 2025, or 2030, this

won’t change.)

The movie is effectively divided into two sections. The first focuses

on the assassination of The Deputy (Yves

Montand) and the second details the investigation of The Judge (Jean-Louis

Trintignant) into what is initially known as “the incident” but is eventually

called “the murder.” Although Costa-Gavras never hides the film’s politics,

this is presented as a thriller with rising tension and even a car chase (as an

attempt is made on a witness’ life). Z’s

theme is that of the lone good man standing against a corrupt system but, in a

brutally realistic twist on the usual triumphant ending, the movie turns the

tables in the closing minutes. The seemingly inevitable victory is stolen away,

leaving behind emptiness, anger, and a sense that this is how the real world works. We see with double vision,

looking equally at events in the 1960s and today – whenever “today” is. (My

guess is that whenever you read this, whether it’s 2018, 2025, or 2030, this

won’t change.)

Z opens with the following caption: “Any similarity to actual persons or events is deliberate.” It then illustrates how right-wing fascism has infected the supposedly democratic government. Liberal/left wing ideology is decried as “mildew.” The Deputy represents everything the government despises and the opportunity to eliminate him is ripe when he speaks at a rally for nuclear disarmament. He is warned beforehand that there might be an attempt on his life but, even following a vicious assault, he soldiers on. Then the fatal attack occurs and his deputies (Charles Denner, Bernard Fresson) and wife (Irene Papas) are left to cope with the aftermath.

Once the focus shifts from The Deputy to the Judge, Z becomes a riveting procedural as the

magistrate, with the help of a photojournalist, seeks to uncover the truth. He

interviews witnesses and his skepticism regarding a high-level conspiracy

evaporates. The use of one particular phrase by three separate witnesses

convinces him that the police have orchestrated testimonies. The Judge refuses

both the carrot (career advancement) and the stick (threats) offered by

right-wing forces to end his investigation quickly with a favorable result.

Once the focus shifts from The Deputy to the Judge, Z becomes a riveting procedural as the

magistrate, with the help of a photojournalist, seeks to uncover the truth. He

interviews witnesses and his skepticism regarding a high-level conspiracy

evaporates. The use of one particular phrase by three separate witnesses

convinces him that the police have orchestrated testimonies. The Judge refuses

both the carrot (career advancement) and the stick (threats) offered by

right-wing forces to end his investigation quickly with a favorable result.

Throughout his career, Costa-Gavras (born Konstantinos Gavras) has been political. Z, his third film, raised him to prominence on the international stage. It was a box office success, especially in many European countries, and won Oscars for Foreign Language Film and Editing. (It was nominated, but did not win, for Director and Picture.) A self-proclaimed communist, Costa-Gavras had no interest in capitulating with motion picture norms (as is evident from Z’s epilogue). His filmography includes many obscure titles alongside such recognizable ones as 1982’s Missing (with Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek), 1988’s Betrayed (written by Joe Eszterhas and starring Tom Berenger), 1989’s Music Box (another Eszterhas-penned script, this one with Jessica Lange), and 1997’s Mad City (with Dustin Hoffman and John Travolta).

The film’s strength today is the same as when it released:

It makes a relevant political point while telling a gripping story in which the

power is concentrated in the wrong hands. The General (Pierre

Dux), the head of police, is effective as a villain because he is always cold,

calm, and rational. He believes his actions to be justified, likening himself to

antibodies attacking the “ideological mildew” of “-isms.” He stands at the

forefront of the populist, “antiforeign” movement that The Deputy opposes. Pierre

Dux’s performance is noteworthy because of its restraint. The same can be said

about Jean-Louis Trintignant, whose Judge is always composed and only

occasionally allows glimpses into his inner thinking. Two of Z’s biggest stars, Yves Montand and

Irene Papas, have relatively small/supporting roles although The Deputy’s

importance casts a long shadow.

The film’s strength today is the same as when it released:

It makes a relevant political point while telling a gripping story in which the

power is concentrated in the wrong hands. The General (Pierre

Dux), the head of police, is effective as a villain because he is always cold,

calm, and rational. He believes his actions to be justified, likening himself to

antibodies attacking the “ideological mildew” of “-isms.” He stands at the

forefront of the populist, “antiforeign” movement that The Deputy opposes. Pierre

Dux’s performance is noteworthy because of its restraint. The same can be said

about Jean-Louis Trintignant, whose Judge is always composed and only

occasionally allows glimpses into his inner thinking. Two of Z’s biggest stars, Yves Montand and

Irene Papas, have relatively small/supporting roles although The Deputy’s

importance casts a long shadow.

If it was merely a conventional 1969 thriller, Z might seem dated by today’s standards. That’s more a reflection of how the genre has changed over the decades with action scenes becoming increasingly sophisticated. Z is thick with exposition and, although it is well-paced, it expects viewers to pay attention. Flashbacks lean heavily on the “flash” in that many of them are little more than one or two-second cuts designed to recall an earlier scene or reinforce a characteristic.

The political element is what crystallizes Z’s timelessness and gives Costa-Gavras the prescience of Nostradamus. A current viewer could be forgiven thinking this was a new movie made using a ‘70s style to tell an allegorical tale. Z doesn’t merely stand the test of time; it transcends it. Watching it today, as was the case when I first saw it in 2006, it’s an eerie, unsettling experience.

Z (Algeria/France, 1969)

Cast: Yves Montand, Irene Papas, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Pierre Dux, George Geret, Charles Denner, Bernard Fresson

Home Release Date: 2019-02-16

Screenplay: Jorge Semprun, based on the novel by Vassili Vassilikos

Cinematography: Raoul Coutard

Music: Mikis Theodorakis

U.S. Distributor: Cinema V

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "PG" (Violence)

Genre: Thriller

Subtitles: In French with subtitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.66:1

- (There are no more worst movies of Yves Montand)

- (There are no more better movies of Irene Papas)

- (There are no more worst movies of Irene Papas)

- Three Colors: Red (1994)

- Amour (2012)

- (There are no more better movies of Jean-Louis Trintignant)

- (There are no more worst movies of Jean-Louis Trintignant)

Comments