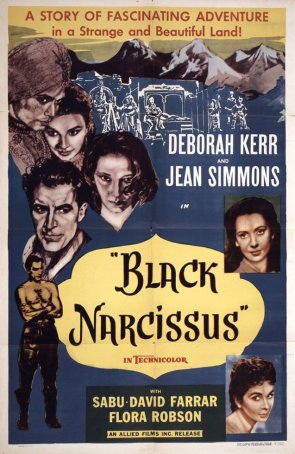

Black Narcissus (United Kingdom, 1947)

April 19, 2020

Watching Black Narcissus without an awareness of the

year in which it was made might result in one concluding that it was the

product of the 1960s. Many aspects of the production – from the storyline’s

sexual undertones to the lush technicolor cinematography (for which Jack

Cardiff won an Oscar) – were decades ahead of their time. However, although

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s film has the look and feel of something

from the auteur’s era, the stars – Deborah Kerr, Jean Simmons, and David Farrar

– place it at the time of its actual release: 1947.

Time, as they say, hasn’t been kind to Black Narcissus.

Viewed through a contemporary lens, the film’s psychological explorations seem

dated and naïve. The storyline, a melodrama about nuns coping with

interpersonal conflicts, repressed lust, and the difficulties of geographical

isolation, is simplistic. The movie also commits what today would be considered

a cardinal sin – having two white actors (Esmond Knight and Jean Simmons) play

ethnic characters by darkening their skin. This was by no means unusual in the

1940s and 1950s (it won Hugh Griffith an Oscar in 1959’s Ben-Hur) but

it’s one of those things that feels unfortunate and anachronistic to modern

viewers.

Although the year in which Black Narcissus transpires

is not specified, it’s most likely set in the interwar years and is obvious

pre-World War II. (The source material, a Rumer Godden novel, was written in

1939.) Set high in the Himalayas (some eight-thousand feet above sea level),

the story concerns a group of Anglican nuns – Sister Superior Clodagh (Deborah

Kerr), Sisters Philippa (Flora Robson), Honey (Jenny Laird), and Briony (Judith

Furse), and the mentally ill Sister Ruth (Kathleen Bryon) – as they seek to convert a deserted palace into a school

and hospital for the locals. As time passes, they find themselves increasingly

separated from the civilized world. A local British agent, Mr. Dean (David

Farrar), attracts the attention of Clodagh, who is haunted by memories of a

failed romance in Ireland, and Ruth, whose instability leads her to believe

Dean is interested in her. Meanwhile, the “Young General” (Sabu) comes to the

convent for his education and falls for Kanchi (Jean Simmons), a seductive

dancing girl whose sole purpose is to seduce him.

Although the year in which Black Narcissus transpires

is not specified, it’s most likely set in the interwar years and is obvious

pre-World War II. (The source material, a Rumer Godden novel, was written in

1939.) Set high in the Himalayas (some eight-thousand feet above sea level),

the story concerns a group of Anglican nuns – Sister Superior Clodagh (Deborah

Kerr), Sisters Philippa (Flora Robson), Honey (Jenny Laird), and Briony (Judith

Furse), and the mentally ill Sister Ruth (Kathleen Bryon) – as they seek to convert a deserted palace into a school

and hospital for the locals. As time passes, they find themselves increasingly

separated from the civilized world. A local British agent, Mr. Dean (David

Farrar), attracts the attention of Clodagh, who is haunted by memories of a

failed romance in Ireland, and Ruth, whose instability leads her to believe

Dean is interested in her. Meanwhile, the “Young General” (Sabu) comes to the

convent for his education and falls for Kanchi (Jean Simmons), a seductive

dancing girl whose sole purpose is to seduce him.

One of my problems with Black Narcissus is that I

never found the characters credible. I didn’t believe any of them and their

interpersonal conflicts contrived and artificial. The acting is fine but, aside

from Farrar’s relaxed performance (think Matthew McConaughey), there’s no

standout. One wonders whether there’s something about the nun’s habits that

inhibits acting – certainly Kerr and Simmons are at their best during the brief

instances when they are allowed to literally let down their hair.

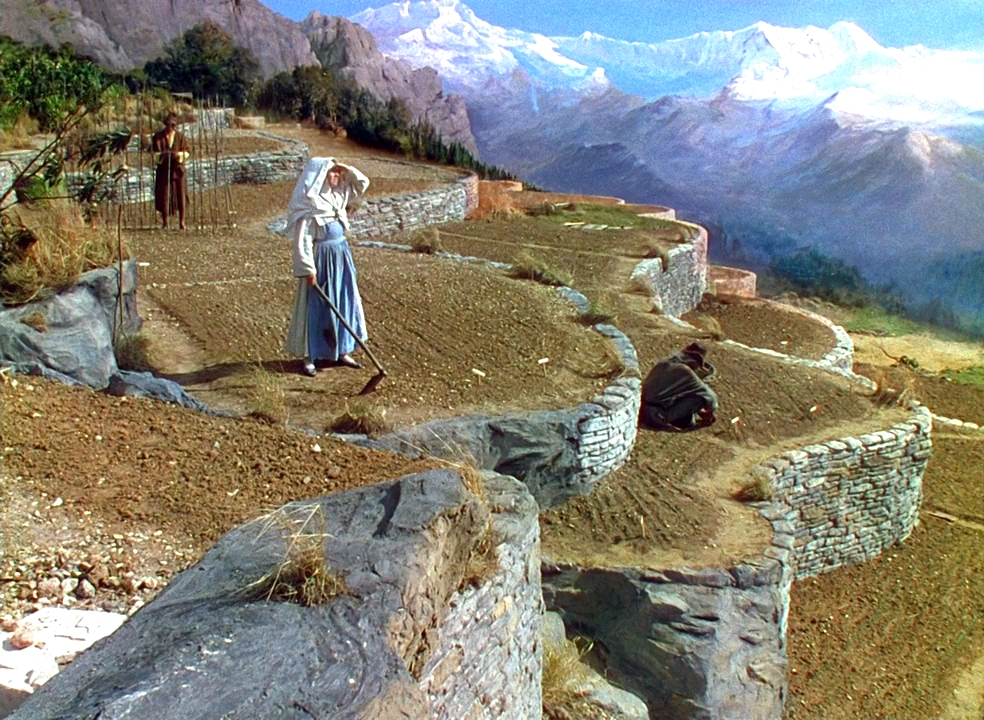

The film’s true star is the setting, but the location is no

more real than Peter Jackson’s Middle Earth. The convent is gorgeously rendered

and its mountaintop location is breathtaking – even though the majority of the

movie was filmed in London’s Pinewood Studios. Powell and Pressburger used

landscape matte paintings by W. Percy Day and scale models to represent the

mountain range and the effectiveness of the techniques are exemplary. When

lighting the shots, cinematographer Jack Cardiff (working in Technicolor – a

rarity for 1947), relied on paintings for inspiration (Vermeer in particular).

This creates a different aesthetic from what one often encounters in early

color films.

The film’s true star is the setting, but the location is no

more real than Peter Jackson’s Middle Earth. The convent is gorgeously rendered

and its mountaintop location is breathtaking – even though the majority of the

movie was filmed in London’s Pinewood Studios. Powell and Pressburger used

landscape matte paintings by W. Percy Day and scale models to represent the

mountain range and the effectiveness of the techniques are exemplary. When

lighting the shots, cinematographer Jack Cardiff (working in Technicolor – a

rarity for 1947), relied on paintings for inspiration (Vermeer in particular).

This creates a different aesthetic from what one often encounters in early

color films.

Narratively, not much happens during the course of the film,

which is primarily about the inevitable failure of the group on nuns to

maintain the convent long-term, despite the help of Mr. Dean and the “Old

General” (Esmond Knight). Clodagh proves unequal to the task – a concern voiced

when she is given the commission by the Mother Superior. Ruth’s instability

grows worse as the mountaintop stay is prolonged. The other nuns have their own

demons to confront. Meanwhile, the locals are wary of the “magical” medicines

used by the sisters and the tentative bond of trust is shattered by a tragedy.

For a movie that features no nudity or explicit male/female

interaction, Black Narcissus revels in sensuality and eroticism.

Clodagh’s desires are strongly repressed but make their way to the surface when

she remembers her failed romance with Con or when she shares the screen with

Mr. Dean. Ruth, allowed to shed her inhibitions as a result of her madness, is

more overtly sensual. In one memorable sequence toward the end, she sheds her

habit in favor of a dress, lets her hair flow free, and puts on makeup. (The

scene in which she applies red lipstick was censored for the US release due to

its suggestive nature.) Kanchi, although

presented as a low-caste dancer, is most likely a prostitute and the looks she

shares with the Young General leave little to the imagination.

During its 1947 release, Black Narcissus, despite

being dogged by censorship in the United States, was seen primarily for its

spectacle elements (being in color was in and of itself a selling point).

Seventy-plus years later, however, the technical aspects – although impressive

considering the special effects limitations of the era – represent a lukewarm

reason to see the film and the storyline, which is only of limited interest,

adds little in the way of a sweetener. Black Narcissus feels

frustratingly incomplete, with character arcs that go nowhere and interpersonal

interactions that feel scripted rather than authentic.

During its 1947 release, Black Narcissus, despite

being dogged by censorship in the United States, was seen primarily for its

spectacle elements (being in color was in and of itself a selling point).

Seventy-plus years later, however, the technical aspects – although impressive

considering the special effects limitations of the era – represent a lukewarm

reason to see the film and the storyline, which is only of limited interest,

adds little in the way of a sweetener. Black Narcissus feels

frustratingly incomplete, with character arcs that go nowhere and interpersonal

interactions that feel scripted rather than authentic.

My lack of enthusiasm for Black Narcissus is not widely shared. The film has a strong core of defenders, led by Martin Scorsese, whose effusive praise of the movie (and its directors) knows no bounds. However, writer George Perry captured my feeling when stating that “the…photography in Technicolor by Jack Cardiff in Black Narcissus was a great deal better than the story and lifted the film above the threatening banality.” For the duo of Powell and Pressburger, who would remain a team until the latter retired from directing in 1957, widespread recognition lay just ahead with The Red Shoes, another Cardiff-lensed Technicolor picture that was released in 1958. Red, not Black, has proven to be the more lasting color when exposed to the shifting sands of time.

Black Narcissus (United Kingdom, 1947)

Cast: Deborah Kerr, Flora Robson, Jenny Laird, Judith Furse, Kathleen Byron, Esmond Knight, Sabu, David Farrar, Jean Simmons, May Hallatt

Home Release Date: 2020-04-19

Screenplay: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, adapted from the novel by Rumer Godden

Cinematography: Jack Cardiff

Music: Brian Easdale

U.S. Distributor: Universal Pictures

- From Here to Eternity (1953)

- (There are no more better movies of Deborah Kerr)

- Casino Royale (1969)

- (There are no more worst movies of Deborah Kerr)

- (There are no more better movies of Flora Robson)

- (There are no more worst movies of Flora Robson)

- (There are no more better movies of Jenny Laird)

- (There are no more worst movies of Jenny Laird)

Comments