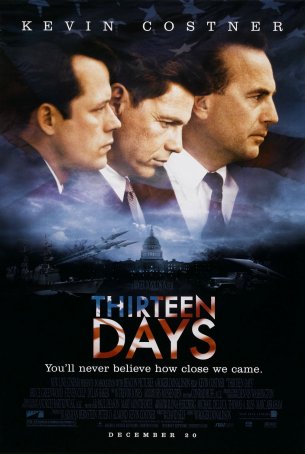

Thirteen Days (United States, 2000)

For thirteen days in 1962, from October 16 through October 28, the world teetered on the brink of nuclear war as the United States and the Soviet Union stood toe-to-toe, neither bending, each waiting for the other to blink. Despite public assurances to the United States that no offensive weapons would be placed on Cuban soil, the Soviets deployed 40 medium range ballistic missiles there, each of which could reach as far as 1000 miles away while carrying a 3 Megaton payload. Within five minutes of a full launch, 80 million Americans could be killed. To political observers, this act represented a shift in Soviet military philosophy from a deterrent position to one of first strike – a situation the United States could not allow to go unchecked. So began a tense standoff, with President Kennedy issuing an ultimatum that he backed up with a naval blockade of Cuba. In the end, as history records it, the USSR backed down and World War III was averted. Employing a script by David Self, director Roger Donaldson opens a window into the behind-the-scenes backstabbing and brinkmanship that went into ending the Cuban Missile Crisis. Like The Contender, Thirteen Days works because it gives the viewer a fly-on-the-wall's perspective of events that change the trajectory of history. In the case of The Contender, the scenario was fictional; for Thirteen Days, it is largely factual. Nevertheless, in large part because both offer such an intimate view of the side of politics that is hidden from the average citizen, there is a great deal of synergy between the films.

To many people living today, the Cuban Missile Crisis is a footnote on page 550 in a high school history text book. By the time Ronald Reagan assumed the greatest role of his career, the Soviet Union was in its terminal phase, with its economy collapsing faster than a rotten railroad overpass during an earthquake. Throughout the '80s and into the '90s, the potential of a nuclear holocaust became increasingly remote. The fact of life that everyone lived with during the '50s, '60s, and '70s now seems as remote as a barely recalled childhood nightmare. So the trick for Thirteen Days was to paint a vivid enough portrait to stir memories in those who lived through the events of October 1962 and to involve those born after that date.

It is often difficult to dramatize recent historical events because nearly everyone going into the theater already knows the outcome. The world did not end with the Cuban Missile Crisis. Disaster was averted with almost no loss of life, and the United States was the "winner" (insofar as there can be a winner in this situation). What's more, Thirteen Days is constructed as a thriller, which means that its intent is to arouse the audience's interest by creating suspense.

Thirteen Days presents a dramatized (i.e., somewhat

fictionalized) view from the top. The three main characters are JFK (Bruce

Greenwood), RFK (Steven Culp), and Kenny O'Donnell (Kevin Costner). Who? If you

haven't heard of O'Donnell, you're not alone. He may have lived in Camelot, but

its mystique did not enshrine him. O'Donnell went to Harvard with Bobby

Kennedy, worked for JFK's Senate and Presidential campaigns, then became a

special advisor to the President with an office next door to the Oval Office.

He was definitely in Kennedy's inner circle. However, his role in the crisis

appears to have been beefed up to give star Kevin Costner more screen time and

greater importance. It is unlikely that some of the decisions and actions

attributed to O'Donnell in this movie actually occurred in real life. Indeed,

while O'Donnell's character was included to give some "balance" to

the script (show a different perspective of events than that of JFK and RFK),

Costner's presence tips the scales in the wrong direction. At times, there's a

sense that Thirteen Days should be devoting more attention to JFK and

RFK and less to a lesser player like O'Donnell.

Thirteen Days presents a dramatized (i.e., somewhat

fictionalized) view from the top. The three main characters are JFK (Bruce

Greenwood), RFK (Steven Culp), and Kenny O'Donnell (Kevin Costner). Who? If you

haven't heard of O'Donnell, you're not alone. He may have lived in Camelot, but

its mystique did not enshrine him. O'Donnell went to Harvard with Bobby

Kennedy, worked for JFK's Senate and Presidential campaigns, then became a

special advisor to the President with an office next door to the Oval Office.

He was definitely in Kennedy's inner circle. However, his role in the crisis

appears to have been beefed up to give star Kevin Costner more screen time and

greater importance. It is unlikely that some of the decisions and actions

attributed to O'Donnell in this movie actually occurred in real life. Indeed,

while O'Donnell's character was included to give some "balance" to

the script (show a different perspective of events than that of JFK and RFK),

Costner's presence tips the scales in the wrong direction. At times, there's a

sense that Thirteen Days should be devoting more attention to JFK and

RFK and less to a lesser player like O'Donnell.

Thirteen Days includes a lot of fascinating elements, the most obvious of which is the struggle between Kennedy's advisors as the hawks and doves seek to sway the President to their point-of-view. Each side has valid objections to the other's position, and it becomes clear that both paths could lead to disaster. Some of the more zealous members of the military, disgusted by a perceived weakness in JFK's approach, seek to trap the President into a warlike position by manipulating the rules of engagement. At one time, JFK's advisors become worried that certain actions may give the impression that the President is fighting down a coup attempt. Meanwhile, the top minds in the United States must attempt to puzzle out Moscow's seemingly contradictory responses to American actions. Are they willing to capitulate and deal beneath the table, or are they setting a trap to give them time to prepare the missiles for use? Tense moments include a confrontation between a U.S. warship and a Soviet sub, attempts by a U-2 plane to avoid missiles, and the final, frenzied negotiations as the deadline looms.

If the film doesn't completely transport the viewer back to

the early '60s, there are enough cues to at least suggest the time period. The

White House of the era has been meticulously re-created using the many

photographs available from JFK's three-year term there. In addition, all of the

fashions, hair styles, and speech patterns are vintage '60s. And, to graft on a

further layer of realism and credibility, bits and pieces of Walter Cronkite's

actual newscasts are presented. To many Americans, things weren't real until

Cronkite spoke them. ("And that's the way it is...")

If the film doesn't completely transport the viewer back to

the early '60s, there are enough cues to at least suggest the time period. The

White House of the era has been meticulously re-created using the many

photographs available from JFK's three-year term there. In addition, all of the

fashions, hair styles, and speech patterns are vintage '60s. And, to graft on a

further layer of realism and credibility, bits and pieces of Walter Cronkite's

actual newscasts are presented. To many Americans, things weren't real until

Cronkite spoke them. ("And that's the way it is...")

Although Costner is fine as O'Donnell, the movie might have been more successful with a lesser-known actor in this part. At this point in his career, Costner arguably brought too much off-screen baggage to his roles, and there are times when his ego appears to have influenced O'Donnell's importance. Plus, the Boston accent doesn't sound right coming out of the actor's mouth - it seems slightly exaggerated, and, as a result, almost comical. The two actors playing opposite Costner are much better. Bruce Greenwood gives a strong interpretation of JFK. Visually, there's only a passing resemblance, but Greenwood has perfected the mannerisms and, more importantly, the style. Meanwhile, Steven Culp is equally as good as JFK's brother and right-hand man, Bobby. Other notable performances include Dylan Baker as Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Michael Fairman as U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson, Kevin Conway as General Curtis LeMay, and Christopher Lawford as Commander William Ecker.

Although the movie runs a little on the long side (a seeming

characteristic of all Kevin Costner vehicles), director Donaldson (No Way

Out, Dante’s Peak) never lets the momentum flag. The final half-hour

features some weak spots, including a little too much non-historical melodrama

and several over-the-top speeches. Some historians may be annoyed at the

liberties taken by Self's screenplay with the established facts, but the writer

claims he spent countless hours poring over documents and listening to tapes in

order to get most of the background correct. Certain aspects were dramatized to

make them more accessible to viewers. This is not, after all, a documentary.

(Several excellent ones exist about the Cuban Missile Crisis.)

Although the movie runs a little on the long side (a seeming

characteristic of all Kevin Costner vehicles), director Donaldson (No Way

Out, Dante’s Peak) never lets the momentum flag. The final half-hour

features some weak spots, including a little too much non-historical melodrama

and several over-the-top speeches. Some historians may be annoyed at the

liberties taken by Self's screenplay with the established facts, but the writer

claims he spent countless hours poring over documents and listening to tapes in

order to get most of the background correct. Certain aspects were dramatized to

make them more accessible to viewers. This is not, after all, a documentary.

(Several excellent ones exist about the Cuban Missile Crisis.)

Thirteen Days' biggest challenge may be finding an audience. For those with an interest in JFK and the Cuban Missile Crisis, it's a worthwhile addition to an already full motion picture cannon. After all, the events depicted here represent one of America's most tense periods and, ultimately, JFK's finest hour. The perspective offered by Thirteen Days is different enough from other movies about the Crisis that it merits viewing.

Thirteen Days (United States, 2000)

Cast: Kevin Costner, Tim Kelleher, Kevin Conway, Frank Wood, Henry Strozier, Michael Fairman, Dylan Baker, Steven Culp, Bruce Greenwood, Bill Smitrovich

Screenplay: David Self

Cinematography: Andrzej Bartkowiak

Music: Trevor Jones

U.S. Distributor: New Line Cinema

U.S. Release Date: 2000-12-25

MPAA Rating: "PG-13" (Profanity)

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- (There are no more better movies of Tim Kelleher)

- (There are no more worst movies of Tim Kelleher)

- Two Family House (2000)

- (There are no more better movies of Kevin Conway)

- Invincible (2006)

- (There are no more worst movies of Kevin Conway)

Comments