Tokyo Story (Japan, 1953)

October 27, 2019

Spoilers! Key plot points from Tokyo Story are revealed in this review.

All-time best lists (such as the one published by Sight and Sound) are a little like “show” libraries stocked with classic volumes of literature. Disputing the preeminence of any of these titles invites censure. In my experience, some of these so-called “great” movies have attained their lofty placement by dint of their reputation rather than on merit. Thankfully, such a cynical perspective need not be universally applicable. Take Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, for example. In addition to being uniquely crafted and influential, it tells a simple story that resonates on many levels. The characters are so real and the situations so believable that it’s easy to get lost in Ozu’s black-and-white representation of postwar Japan and not realize that two hours have passed. In an era when movies seek to be bigger and bolder than ever before, the anti-spectacle of Tokyo Story derives power from its “smallness.”

Watching Tokyo Story, I was reminded of the 1974 Harry Chapin song, “Cat’s in the Cradle.” This verse in particular is relevant:

“I've long since retired and my son's moved away.

I called him up just the other day

I said, I'd like to see you if you don't mind

He said, I'd love to, dad, if I could find the time

You see, my new job's a hassle, and the kids have the flu

But it's sure nice talking to you, dad

It's been sure nice talking to you.”

Chapin penned those words 20 years after Ozu and co-writer

Kogo Noda committed the script for Tokyo

Story to paper, yet they express the same sentiment: children leaving

behind parents – a cycle of life that is so normal we rarely think about it.

Yet, upon reflection, there’s something poignant about the disintegration of a

family that often isn’t fully realized until long after it has happened.

Chapin penned those words 20 years after Ozu and co-writer

Kogo Noda committed the script for Tokyo

Story to paper, yet they express the same sentiment: children leaving

behind parents – a cycle of life that is so normal we rarely think about it.

Yet, upon reflection, there’s something poignant about the disintegration of a

family that often isn’t fully realized until long after it has happened.

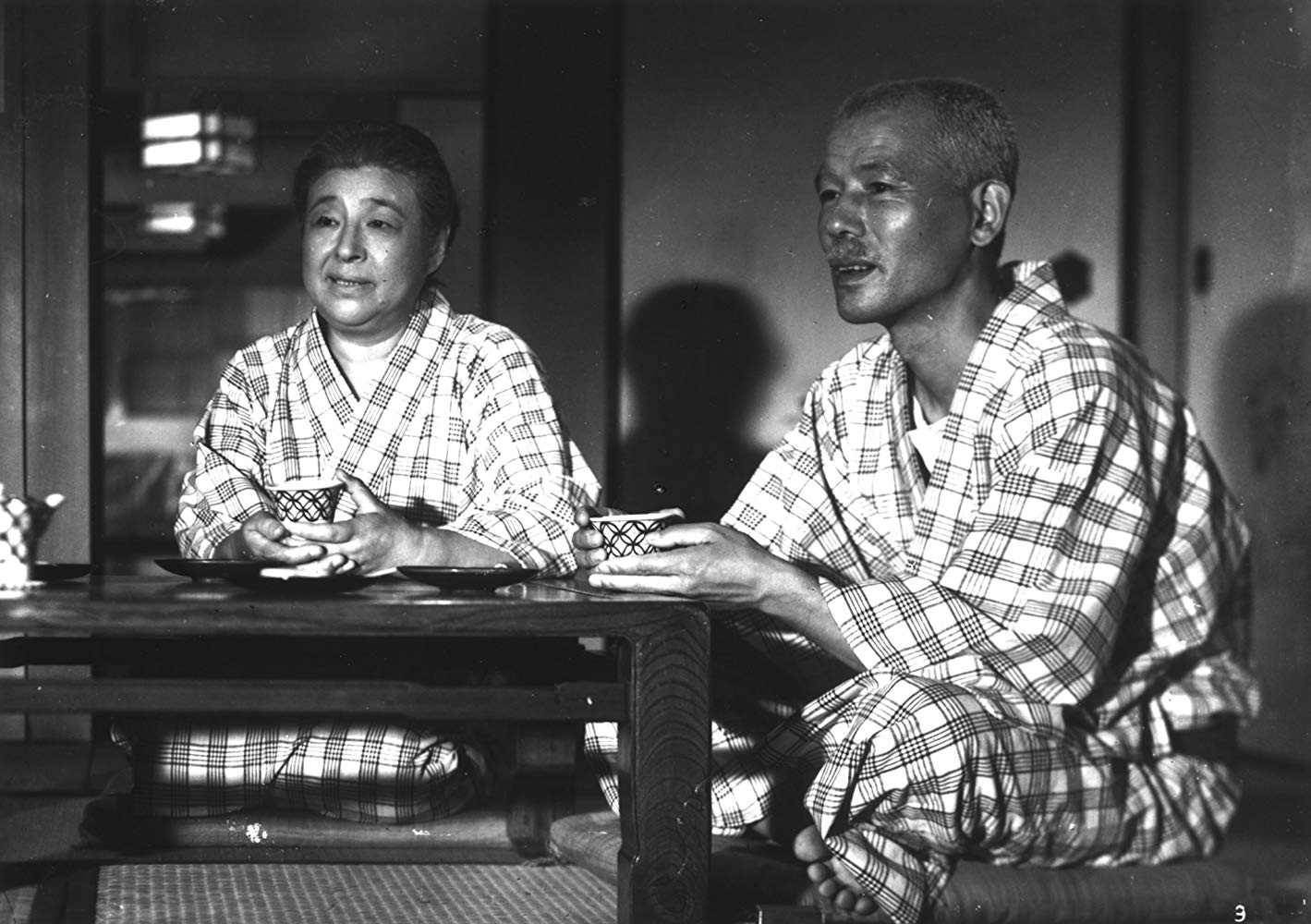

Tokyo Story can be divided into two sections. The first, loosely inspired by Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow, shows the interaction between two aging parents and their adult children. The elderly couple – Shukichi Hirayama (longtime Ozu collaborator Chishu Ryu) and his wife, Tomi (Chieko Higashiyama) – arrive in Tokyo to spend time with their oldest son, Koichi (So Yamamura), and their daughter, Shige (Haruko Sugimura), as well as their widowed daughter-in-law, Noriko (Setsuko Hara). Koichi and Shige, however, are so absorbed in their own affairs that they have little time to devote to their parents, and pawn sight-seeing duties off on Noriko, who is more than happy to oblige. Following her husband’s death, she has spent a quiet, solitary existence and is delighted to spend time with her in-laws.

The second portion of Tokyo

Story focuses on the impact of Tomi’s death on the rest of the family.

During the return journey from Tokyo to Onomichi, Tomi becomes ill. By the time

she gets home, her condition is serious. The rest of the family is informed.

Koichi, Shige, and Noriko make the trip by train to join their father and

youngest sister, Kyoko (Kyoko Kagawa), in a bedside vigil. Another son, Keizo

(Shiro Osaka), arrives shortly after his mother’s death. The rest of Tokyo Story is a mediation on how Tomi’s

death impacts the survivors – the sharp-but-short-lived grief suffered by

Koichi, Shige, and Keizo; the deeper feelings felt by Noriko and Kyoko; and the

life-altering loneliness that takes hold of Shukichi.

The second portion of Tokyo

Story focuses on the impact of Tomi’s death on the rest of the family.

During the return journey from Tokyo to Onomichi, Tomi becomes ill. By the time

she gets home, her condition is serious. The rest of the family is informed.

Koichi, Shige, and Noriko make the trip by train to join their father and

youngest sister, Kyoko (Kyoko Kagawa), in a bedside vigil. Another son, Keizo

(Shiro Osaka), arrives shortly after his mother’s death. The rest of Tokyo Story is a mediation on how Tomi’s

death impacts the survivors – the sharp-but-short-lived grief suffered by

Koichi, Shige, and Keizo; the deeper feelings felt by Noriko and Kyoko; and the

life-altering loneliness that takes hold of Shukichi.

Tokyo Story is an ensemble piece, concentrating on all the members of a family. Each has a role to play in the overall drama but none is more central than Noriko – the only primary character who is not blood-related to the others. Because of the compassion she shows for her in-laws, she can be seen as the most generous and least self-serving of the younger individuals (something she vehemently denies when Shukichi thanks her for her help during the Tokyo visit and after his wife’s death). In a conversation with Kyoko, who chafes about the “selfishness” of her siblings, Noriko presents the counter-argument: that Koichi and Shige have their own lives and families and their first loyalties are to them.

Ozu’s characteristic style – a filmmaking collage that would become familiar to all those who studied his life’s work – is evident throughout Tokyo Story and explains why the movie wields such power. Ozu isn’t interested in inserting himself into the story. He uses simple, static shots without directorial flourishes to maximize the audience’s ability to understand the characters. For most scenes, the camera is placed in a fixed position, approximately two feet above the floor. As a result, the viewer is often looking up at the characters (unless they are seated). Instead of moving the camera (something that happens only once in all of Tokyo Story – during a sequence when Shukichi and Tomi are walking across a bridge), Ozu stops the shot and relocates to another position. Many scenes open and close with images of unoccupied spaces. When the director employs close-ups, he often has the actor look directly at the camera rather than off to one side.

Overt melodrama is not an Ozu hallmark. In fact, he works

hard to avoid it. Key events that might form the background of a Hollywood

production occur off-screen and are referenced in dialogue. (In Tokyo Story, for example, Tomi’s

worsening illness is referenced by her children as they receive telegrams

informing them about it.) The camera’s perspective keeps a certain distance

between the viewer and the characters. That’s not to say there’s no emotional

impact but it’s not the kind of manipulative, overwrought influence favored by

major American studio productions. This is more subtle and ultimately results

in a deeper, lasting impression. It encourages not only feeling in the moment but also reflecting on the themes and ideas

explored by the narrative.

Overt melodrama is not an Ozu hallmark. In fact, he works

hard to avoid it. Key events that might form the background of a Hollywood

production occur off-screen and are referenced in dialogue. (In Tokyo Story, for example, Tomi’s

worsening illness is referenced by her children as they receive telegrams

informing them about it.) The camera’s perspective keeps a certain distance

between the viewer and the characters. That’s not to say there’s no emotional

impact but it’s not the kind of manipulative, overwrought influence favored by

major American studio productions. This is more subtle and ultimately results

in a deeper, lasting impression. It encourages not only feeling in the moment but also reflecting on the themes and ideas

explored by the narrative.

Although Tokyo Story was well-received during its initial Japanese run, it wasn’t exported to the West until after Ozu’s death. As such, he didn’t live long enough to see his name enshrined alongside that of his fellow countryman, Akira Kurosawa, on the international stage. Ironically, the original reason for distributors to reject Tokyo Story was a belief that it was “too Japanese.” In reality, with its universally relatable themes, it’s anything but “too Japanese.” Alongside Late Spring, Early Summer, An Autumn Afternoon, and Floating Weeds, Tokyo Story remains one of Ozu’s most memorable achievements. It is his best-known work and the crown jewel of his filmography.

Families breaking up, children drifting away from their parents – those are the natural rhythms of life distilled by a master craftsman into 134 minutes of screen time. Tokyo Story is as much a journey of discovery as it is an opportunity to reflect. The characters populating this film aren’t strangers. They are our parents, our children, ourselves.

Tokyo Story (Japan, 1953)

Cast: Chishu Ryu, Chieko Higashiyama, So Yamamura, Haruko Sugimura, Setsuko Hara, Kyoko Kagawa, Shiro Osaka

Home Release Date: 2019-10-27

Screenplay: Yasujiro Ozu & Kogo Noda

Cinematography: Yuharu Atsuta

Music: Takanobu Saito

U.S. Distributor: New Yorker Films

- Autumn Afternoon, An (1963)

- Bad Sleep Well, The (1963)

- (There are no more better movies of Chishu Ryu)

- (There are no more worst movies of Chishu Ryu)

- (There are no more better movies of Chieko Higashiyama)

- (There are no more worst movies of Chieko Higashiyama)

- (There are no more better movies of So Yamamura)

- (There are no more worst movies of So Yamamura)

Comments