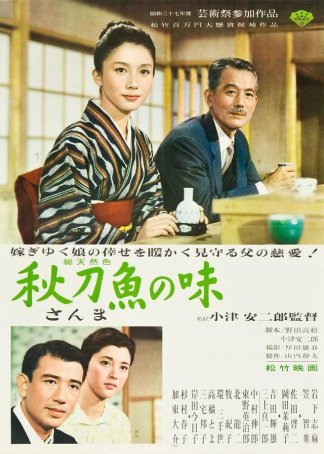

Autumn Afternoon, An (Japan, 1962)

March 22, 2019

Yasujiro Ozu is widely regarded as one of Japan’s two greatest filmmakers. Unlike his contemporary, Akira Kurosawa, Ozu didn’t receive worldwide recognition until after his death in 1963. Although Kurosawa was well-known in the West during his lifetime, Ozu’s work wasn’t readily available in Europe or North America until the mid-1960s. His best-known masterpiece was 1953’s Tokyo Story. An Autumn Afternoon, his final motion picture, occupies the “inner circle” of great films in Ozu’s oeuvre alongside the likes of Late Spring, Early Summer, and Floating Weeds.

By the time he made An Autumn Afternoon, Ozu’s hallmark style was fully mature. In his review of the film, Roger Ebert made the following observation: “He embodies this vision in a cinematic style so distinctive that you can tell an Ozu film almost from a single shot.” Especially in his later films, Ozu abandoned tracking shots and camera movement altogether. He placed the camera on a tripod (at a low height – approximately two feet off the floor) and cut between static shots to develop dialogue. Scenes often begin and end with lengthy pauses in which the camera temporarily focuses on empty corridors, rooms, or streets while waiting for an actor to enter. Framing is done carefully with objects being strategically placed. In An Autumn Afternoon, there are clocks in many scenes – these establish the time of day to help orient the viewer. Ozu’s ubiquitous teapot makes an appearance as well, as it did in many of the director’s films.

An Autumn Afternoon, like many of Ozu’s films, has a clearly-defined narrative but eschews melodrama. The director observes the behavior of his characters in a series of ordinary situations but skips over scenes that Hollywood would relish. One of the focal points of this movie is the marriage of a young woman. Ozu provides us with a glimpse of her in her wedding dress. The next scene occurs the day after the ceremony with the marriage being referred to in the past tense.

The film transpires in 1962 Tokyo. At the time, Japanese

society was transitioning from post-war reconstruction to the eventual

technological and economic giant it would become during the 1980s. Ozu notes

the growing industrialization and modernization through a series of shots of

factories and smokestacks. He also contrasts the Japan of the early 20th

century, as shown in shots of lower-class neighborhoods, with the shiny promise

of the future. Although nearly two decades past its end, the war remains a scab

on the nation’s collective consciousness. At one point, two characters fantasize

about what might have happened if Japan had won the war before wondering

whether losing it might have been the best outcome.

The film transpires in 1962 Tokyo. At the time, Japanese

society was transitioning from post-war reconstruction to the eventual

technological and economic giant it would become during the 1980s. Ozu notes

the growing industrialization and modernization through a series of shots of

factories and smokestacks. He also contrasts the Japan of the early 20th

century, as shown in shots of lower-class neighborhoods, with the shiny promise

of the future. Although nearly two decades past its end, the war remains a scab

on the nation’s collective consciousness. At one point, two characters fantasize

about what might have happened if Japan had won the war before wondering

whether losing it might have been the best outcome.

The main character is a fifty-something office worker, Shuhei Hirayama (played by Ozu regular Chishu Ryu), who represents as “everyday” a person as one is likely to find. The widowed Hirayama (it is hinted but not explicitly stated that his wife died during the war) lives with his two youngest children, his 21-year old son, Kazuo (Shin’ichiro Mikami), and his 24-year old daughter, Michiko (Shima Iwashita). An older son, Koichi (Keiji Sada), lives separately with his wife, Akiko (Mariko Okada). Most of An Autumn Afternoon transpires inside bars, restaurants, Hirayama’s home and office, and the apartment of Koichi and Akiko. There are two parallel stories. The first involves Hirayama’s growing awareness that his daughter’s future happiness might be assured by “marrying her off” and that, as comfortable as she is caring for her father, the current situation could become a millstone. The second shows the friction between Koichi and Akiko as his compulsive spending conflicts with her frugality.

Other characters in the film include Hirayama’s friends, Kawai (Nobuo Nakamura) and Horie (Ryuji Kita), with whom he frequently meets for drinks and meals. Horie is married to a much younger woman and this becomes as common a point of discussion as the need for Michiko to be married. (Kawai has a candidate for her future husband.) Hirayama’s attitude regarding his daughter’s future happiness changes after spending time with an old professor, “The Gourd” (Eijiro Tono), who lives alone with his despairing middle-aged daughter. The Gourd, having imbibed too much sake, admits that he made a mistake by not marrying her off.

An Autumn Afternoon

is a mediation on sacrifice – an examination of how a parent, after raising and

caring for a child for 20 years, must learn to let go for the betterment of

that child. The Gourd, by keeping his daughter at home, has doomed her to a

life of servitude (while he’s alive) and loneliness (after he dies). Familial

relationships are at the heart of many of Ozu’s films. And, although the

director never married and never had a child (he lived almost his entire life

with his mother, who died a few months before he did), he shows a powerful

empathy for the ordeal of the father/mother when cutting the final ties. In one

conversation, Hirayama and his friends ponder how fast it all goes.

An Autumn Afternoon

is a mediation on sacrifice – an examination of how a parent, after raising and

caring for a child for 20 years, must learn to let go for the betterment of

that child. The Gourd, by keeping his daughter at home, has doomed her to a

life of servitude (while he’s alive) and loneliness (after he dies). Familial

relationships are at the heart of many of Ozu’s films. And, although the

director never married and never had a child (he lived almost his entire life

with his mother, who died a few months before he did), he shows a powerful

empathy for the ordeal of the father/mother when cutting the final ties. In one

conversation, Hirayama and his friends ponder how fast it all goes.

Although many of the themes in An Autumn Afternoon are timeless, the film itself represents a snapshot of Japanese lifestyle in the 1960s. Because the movie was made in color (all but six of Ozu’s 54 films were in black-and-white), there’s a sense of fly-on-the-wall realism to the characters’ everyday interactions. Most of what An Autumn Afternoon depicts has either disappeared or is disappearing: the faithful businessman with a regimented routine, the subservient role of women (who often leave their jobs after marrying), and the acceptance of public drunkenness (everyone in the movie drinks to excess, reflecting Ozu’s own alcoholic tendencies). This aspect gives greater value to An Autumn Afternoon than it had at the time of its release. Almost hypnotic in its unhurried and unvarnished study of one middle-aged Japanese man and the way his perspective of life changes, the movie is deserving of the universal praise it has received from critics and non-critics alike.

To close, I’ll borrow comments from a supplement provided on the Criterion DVD, where French critics Michel Ciment and Georges Perec discuss Ozu, his style, and his intentions. (It’s an excerpt from the French TV show Ciné regards aired on November 26, 1978, entitled “Yasujiro Ozu and the Taste of Sake.”) Their words perfectly encapsulate the experience of watching An Autumn Afternoon and why Ozu’s methodical approach enraptures when it could easily have bored. Ciment says this: “In Zen philosophy...All that counts is the present moment. So what you sense on screen with Ozu is this rapture, this intensity of the present lived moment.” Perec adds: “What he describes is…what’s happening when nothing is going on.”

Autumn Afternoon, An (Japan, 1962)

Cast: Chishu Ryu, Shima Iwashita, Keiji Sada, Mariko Okada, Shin’ichiro Mikami, Nobuo Nakamura, Eijiro Tono, Ryuji Kita

Home Release Date: 2019-03-22

Screenplay: Kogo Noda & Yasujiro Ozu

Cinematography: Yuhara Atsuta

Music: Takanobu Saito

U.S. Distributor: Shochiku Films of America

- Tokyo Story (1953)

- Bad Sleep Well, The (1963)

- (There are no more better movies of Chishu Ryu)

- (There are no more worst movies of Chishu Ryu)

- (There are no more better movies of Shima Iwashita)

- (There are no more worst movies of Shima Iwashita)

- (There are no more better movies of Keiji Sada)

- (There are no more worst movies of Keiji Sada)

Comments