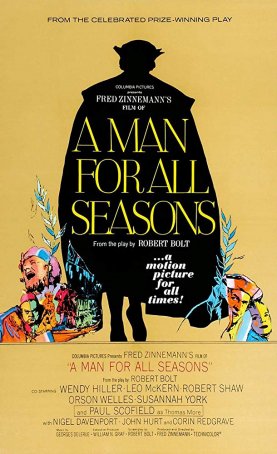

Man for All Seasons, A (United Kingdom, 1966)

January 31, 2019

There are times when A Man for All Seasons seems like an older, gentler uncle to George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones. (Martin was in part inspired by some of the more salacious and bloody episodes of English history, particularly during the 1400s and 1500s.) One can also see reflections of the current state of American politics in the text. Consider this comment made by the protagonist and title character, Thomas More (Paul Scofield): “But since we see that abhorrence, anger, pride, and stupidity commonly profit far beyond charity, modesty, justice, and thought, perhaps we must stand fast a little - even at the risk of being heroes.” The cynical truth of this observation is fully at home in the 21st century.

The 1967 Academy Award winner based on Robert Bolt’s 1960

play, A Man for All Seasons recounts

the struggle between Henry VIII (Robert Shaw) and Sir Thomas More during the final

years of the latter man’s life. Focused on the king’s desire to marry his

paramour, Anne Boleyn (Vanessa Redgrave), and his decision to separate from the

Roman Catholic Church, A Man for All

Seasons shows the schism that divides Henry from More and the events that

lead to the latter’s execution for high treason. Although the film, directed by

Fred Zinnemann from Bolt’s screenplay, is faithful in broad strokes to the

historical record, it takes notable liberties (although, to be fair, the

specifics surrounding individuals and events during the 16th century

are at times murky). It’s a tale of politics and how the nobility of a good man

can’t stand against the whims of a tyrant.

The 1967 Academy Award winner based on Robert Bolt’s 1960

play, A Man for All Seasons recounts

the struggle between Henry VIII (Robert Shaw) and Sir Thomas More during the final

years of the latter man’s life. Focused on the king’s desire to marry his

paramour, Anne Boleyn (Vanessa Redgrave), and his decision to separate from the

Roman Catholic Church, A Man for All

Seasons shows the schism that divides Henry from More and the events that

lead to the latter’s execution for high treason. Although the film, directed by

Fred Zinnemann from Bolt’s screenplay, is faithful in broad strokes to the

historical record, it takes notable liberties (although, to be fair, the

specifics surrounding individuals and events during the 16th century

are at times murky). It’s a tale of politics and how the nobility of a good man

can’t stand against the whims of a tyrant.

According to the Catholic Church, More was martyred when the

executioner deprived him of his head. According to Henry, it was an act of

necessity – his former Lord Chancellor and one-time friend had refused to

acknowledge his break with the Pope as legitimate and, because More was

respected and had influence, his intransigence could foment unrest. (More would

neither sign a letter requesting the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine

of Aragon nor recite the Oath of Supremacy that set aside the Pope as the head

of the Church of England in favor of the king.) The movie dramatizes events in

the manner of a Masterpiece Theater

episode, with a surfeit of dialogue and one-on-one character interaction. The film’s

talkiness is understandable, being based on a stage production, and there’s

still room for tension as the point of the king’s metaphorical sword, wielded

by Thomas Cromwell (Leo McKern) and Richard Rich (John Hurt), pins More down.

In the end, he is faced with a no-win choice: lose his integrity or his head.

According to the Catholic Church, More was martyred when the

executioner deprived him of his head. According to Henry, it was an act of

necessity – his former Lord Chancellor and one-time friend had refused to

acknowledge his break with the Pope as legitimate and, because More was

respected and had influence, his intransigence could foment unrest. (More would

neither sign a letter requesting the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine

of Aragon nor recite the Oath of Supremacy that set aside the Pope as the head

of the Church of England in favor of the king.) The movie dramatizes events in

the manner of a Masterpiece Theater

episode, with a surfeit of dialogue and one-on-one character interaction. The film’s

talkiness is understandable, being based on a stage production, and there’s

still room for tension as the point of the king’s metaphorical sword, wielded

by Thomas Cromwell (Leo McKern) and Richard Rich (John Hurt), pins More down.

In the end, he is faced with a no-win choice: lose his integrity or his head.

Acting is one of A Man

for All Season’s hallmarks and tremendous performances abound. The cast is

loaded with respected names. Paul Scofield (who played the role on stage in

London and during the play’s Broadway run) won his Academy Award for this

carefully contained performance, which matched the ability to deliver erudite

discourse with a sly wit. More’s occasional bursts of righteous anger have

power because, for the most part, Scofield portrays him as a quiet, carefully

controlled individual. Supporting Scofield, and also Oscar-nominated (although

neither won), are Wendy Hiller as More’s wife, Alice, and a blustery Robert

Shaw. Leo McKern, TV’s Rumpole later in his life, plays an ancestor to the

infamous future Lord Protector of England (a part that, like Scofield, he

played on Broadway), and Nigel Davenport is the Duke of Norfolk. Orson Welles, moving

into a later stage of his career, has a small role as Cardinal Wolsey, and John

Hurt’s appearance represented an early role in a storied career. For her

unbilled cameo as Anne Boleyn, Vanessa Redgrave accepted no salary.

A Man for All Seasons

was one of the last highly-regarded films to be helmed by Fred Zinnemann. He

won Oscars both for the movie and his direction. It was his second such victory,

the other having come for From Here to Eternity. Earlier in his career, which stretched all the way back into the

1930s, he shepherded the classic Gary Cooper Western High Noon to the screen. His follow-up to From Here to Eternity was the musical Okalahoma!, a lighthearted departure from his normally serious

fare. With the limited settings and minimal action of A Man for All Seasons, Zinnemann lets the actors take over. The

color cinematography is crisp and clean and there are no directorial flourishes.

The film’s drama emerges through the dialogue and the interplay between the

characters and Zimmermann understood the importance of emphasizing those

production aspects.

A Man for All Seasons

was one of the last highly-regarded films to be helmed by Fred Zinnemann. He

won Oscars both for the movie and his direction. It was his second such victory,

the other having come for From Here to Eternity. Earlier in his career, which stretched all the way back into the

1930s, he shepherded the classic Gary Cooper Western High Noon to the screen. His follow-up to From Here to Eternity was the musical Okalahoma!, a lighthearted departure from his normally serious

fare. With the limited settings and minimal action of A Man for All Seasons, Zinnemann lets the actors take over. The

color cinematography is crisp and clean and there are no directorial flourishes.

The film’s drama emerges through the dialogue and the interplay between the

characters and Zimmermann understood the importance of emphasizing those

production aspects.

A Man for All Seasons broke the two-year run of musicals winning the top Oscar and marked a turn by the Academy Awards toward serious, prestige films. Although a smattering of comedies and one more musical would be honored over the next decade, A Man for All Seasons augured the direction in which the Oscars would ultimately go – impeccably crafted, “important” motion pictures. Due in part to its period setting, the film has aged well, although this type of drama has slipped out of the mainstream and into the realm of the art-house. A Man for All Seasons offers an engaging, if somewhat dry, history lesson leavened with enough low-key drollness and powerful acting to keep it from ever becoming boring.

Man for All Seasons, A (United Kingdom, 1966)

Cast: Paul Scofield, Wendy Hiller, Leo McKern, Robert Shaw, Orson Welles, Susannah York, Nigel Davenport, John Hurt

Home Release Date: 2019-01-31

Screenplay: Robert Bolt, from his play

Cinematography: Ted Moore

Music: Georges Delerue

U.S. Distributor: Columbia Pictures

- Quiz Show (1994)

- (There are no more better movies of Paul Scofield)

- (There are no more worst movies of Paul Scofield)

- (There are no more better movies of Wendy Hiller)

- (There are no more worst movies of Wendy Hiller)

- (There are no more better movies of Leo McKern)

- (There are no more worst movies of Leo McKern)

Comments