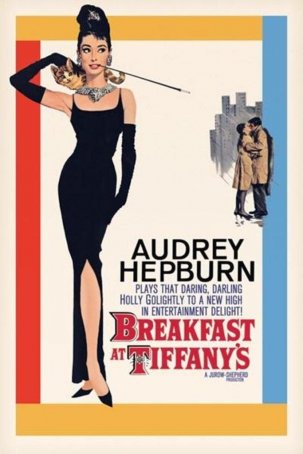

Breakfast at Tiffany's (United States, 1961)

The trajectories traversed by the careers of certain directors can be strange and unfathomable things. Take Blake Edwards, for example. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Edwards was an A-list filmmaker with a string of impressive titles on his resume: Breakfast at Tiffany's, Days of Wine and Roses, 10, and (of course) The Pink Panther series. With the 1980s and 1990s, however, Edwards' reputation went into a meltdown as each successive outing became less enjoyable and more tiresome: The Man Who Loved Women, A Fine Mess, Blind Date, Skin Deep, Switch, and The Son of the Pink Panther.

Were it not for the better Pink Panther entries, Breakfast at Tiffany's would likely be the crown jewel of Edwards' career. Although the 1961 romantic comedy would not appear on many critics' all-time best lists, it remains a favorite among the general movie-going community and, over the years, has developed a legion of die-hard supporters. The film has more charm than the average romantic comedy, but, when considered from a bare-bones perspective, it follows most of the rules that define the genre. The ending, for example, is pure Hollywood, as are many of the steps taken by George Axelrod's screenplay to get us there from the opening credits.

Breakfast at Tiffany's is based on a novella by Truman Capote, and recounts one man's fascination with and love for a fellow inhabitant of his mid-scale New York City apartment building. While many of the book's broad strokes (and even a few of the details) were retained in Axelrod's script, changes were instituted to make the movie more palatable to a mainstream audience. Chief of these is the nature of the relationship between the two leads, which results in a new, different, and more optimistic finale.

Star power is a

key to Breakfast at Tiffany's success. This is a showcase for Audrey

Hepburn who, at age 32, was in her acting prime. (Ironically, Capote championed

giving the part to Marilyn Monroe.) Although never a "great" actress

in the traditional sense, Hepburn possessed charisma and screen presence, and

this era was her time to shine. With Sabrina, Roman Holiday, War and Peace,

and Funny Face behind her, and My Fair Lady still to come,

Hepburn was an undeniable box office draw. Her interpretation of Breakfast

at Tiffany's lead, Holly Golightly, is nearly perfect. And it isn't just

the countless costume changes (although style and elegance have always been

Hepburn's defining characteristics). Actually, this is not an easy role; it

requires Hepburn to do more than smile at the camera and drawl her lines -

although Holly at first appears to be little more than an airheaded,

jet-setting socialite, the more we get to know her, the more we understand the

pain and loss that have led her to embrace her current lifestyle. Holly has low

self-esteem and a sordid past, and she has surrounded herself with bright,

gaudy things in an effort to give herself a level of comfort. She's a phony,

but, in the words of a supporting character, she's a "real" phony.

Star power is a

key to Breakfast at Tiffany's success. This is a showcase for Audrey

Hepburn who, at age 32, was in her acting prime. (Ironically, Capote championed

giving the part to Marilyn Monroe.) Although never a "great" actress

in the traditional sense, Hepburn possessed charisma and screen presence, and

this era was her time to shine. With Sabrina, Roman Holiday, War and Peace,

and Funny Face behind her, and My Fair Lady still to come,

Hepburn was an undeniable box office draw. Her interpretation of Breakfast

at Tiffany's lead, Holly Golightly, is nearly perfect. And it isn't just

the countless costume changes (although style and elegance have always been

Hepburn's defining characteristics). Actually, this is not an easy role; it

requires Hepburn to do more than smile at the camera and drawl her lines -

although Holly at first appears to be little more than an airheaded,

jet-setting socialite, the more we get to know her, the more we understand the

pain and loss that have led her to embrace her current lifestyle. Holly has low

self-esteem and a sordid past, and she has surrounded herself with bright,

gaudy things in an effort to give herself a level of comfort. She's a phony,

but, in the words of a supporting character, she's a "real" phony.

Opposite Hepburn, playing struggling author Paul Varjak, is George Peppard. Although Peppard's star never ascended to the level of Hepburn's (he is probably best remembered for two TV programs: "Banacek" and "The A-Team"), for at least one movie he gets to stand in the spotlight (although about all he does is "stand" - the script requires minimal range from Peppard, and, as a result, his performance comes across as somewhat bland). He and Hepburn generate an effective level of chemistry. Their on-screen interaction has a breezy, natural feel to it, allowing us to believe that their characters click.

Breakfast at Tiffany's uses a simple story to good effect. The film starts by introducing us to Holly as she window shops her way through Manhattan. Paul, an author with a bad case of writer's block, is the new tenant in her building. The two meet on the morning Paul moves in, when he drops by to use Holly's phone. Soon after, they become friends. One night, when a drunk man is banging threateningly on Holly's door, she climbs the fire escape and slips into Paul's apartment. As thanks for "rescuing" her, she invites him to a party, which turns into a loud, rowdy affair. He again comes to her aid when a figure from her past shows up in New York. She inspires him to start writing again. And, for one memorable day, they go out on the town together doing things they have never before done, like shopping at Tiffany's (new for him) and checking out a book from a library (new for her). Ultimately, their feelings end up running more deeply than a normal friendship, but, when Paul confesses his love, Holly rebuffs him. She has set her heart on marrying a rich South American (Villalonga) so she will have enough money to support herself and her brother, whose tour of duty in the army is nearly over.

Neither Holly nor

Paul is a model citizen. In order to finance her wasteful lifestyle, Holly

accepts a weekly payment of $100 to visit an ex-mob boss in prison and carry a

verbal message to his "lawyer." It's a subtle form of prostitution

with no sex involved. The same isn't true of Paul, who could charitably be

called a "kept man" (although a gigolo might be more apropos). His

lover (Patricia Neal) is a well-to-do woman with a much older husband. She

sneaks out to see Paul whenever she gets the opportunity, and his latest

apartment is a gift from her. Every time she departs his bed, she leaves behind

a care package of greenbacks.

Neither Holly nor

Paul is a model citizen. In order to finance her wasteful lifestyle, Holly

accepts a weekly payment of $100 to visit an ex-mob boss in prison and carry a

verbal message to his "lawyer." It's a subtle form of prostitution

with no sex involved. The same isn't true of Paul, who could charitably be

called a "kept man" (although a gigolo might be more apropos). His

lover (Patricia Neal) is a well-to-do woman with a much older husband. She

sneaks out to see Paul whenever she gets the opportunity, and his latest

apartment is a gift from her. Every time she departs his bed, she leaves behind

a care package of greenbacks.

Although both characters have their faults and hard edges, Breakfast at Tiffany's is still first and foremost a fantasy. The use of Henry Mancini's glorious "Moon River" cements the dreamy atmosphere which is introduced at the beginning of the film with establishing shots of a New York City that never was. This is not the real world; it's another sort of place, where Mafia dons are nice men, disappointed suitors react with grace, and improbable lovers can overcome the odds and live life happily ever after. And Holly Golightly is a product of this environment.

Two particular attributes set Breakfast at Tiffany's apart from the overfamiliar continuum of romantic comedies. The first is character depth, particularly where Holly is concerned. Despite her name and her lighthearted disposition, she is actually a troubled individual. Orphaned at an early age, she married the kindly Doc Golightly at the age of 14, then abandoned him for a stint in Hollywood. As played by Buddy Ebson, Doc appears to be a genial elder gentleman, but there's something ambiguous and less-than-wholesome about his relationship with Holly. There's also a question about the status of their marriage. She claims it was annulled long ago, but her tendency to live in a world of her own creation brings that into question. For the most part, Holly has done her best to forget the past, but there are instances when it creeps into her mood, turning her sad and wistful.

Then there's the

dialogue, which, although neither sparkling nor peppered with scintillating

one-liners, is nevertheless solidly written and enjoyable to listen to. The key

to its effectiveness is that conversations do not feel truncated - they are

allowed to run on naturally. The film's best scenes involve Holly and Paul

doing nothing more complicated than talking to each other. Over the years,

strong dialogue has been an important characteristic of all the great romantic

comedies, from The Philadelphia Story to Before Sunrise.

Then there's the

dialogue, which, although neither sparkling nor peppered with scintillating

one-liners, is nevertheless solidly written and enjoyable to listen to. The key

to its effectiveness is that conversations do not feel truncated - they are

allowed to run on naturally. The film's best scenes involve Holly and Paul

doing nothing more complicated than talking to each other. Over the years,

strong dialogue has been an important characteristic of all the great romantic

comedies, from The Philadelphia Story to Before Sunrise.

For a movie made in the early 1960s, Breakfast at Tiffany's is surprisingly bold. Audrey Hepburn is shown in a number of provocative and revealing costumes (the trailer trumpets that the film offers the actress "as you've never seen her before"), and the screenplay includes several forthright lines with a clear sexual connotation. There also isn't any beating around the bush when it comes to the nature of Paul's secondary profession. Throughout his career, Edwards has never had difficulty pushing envelopes (witness Victor/Victoria or the lightsaber condom scene in the otherwise wretched Skin Deep), and this tendency is evident even at this early stage.

Breakfast at

Tiffany's most glaring fault

was not considered a problem during the movie's initial release. However,

looking back through a 40-year window, the inclusion of the stereotyped Asian

character of Mr. Yunioshi (played by Mickey Rooney) borders on offensive. Mr.

Yunioshi's sole purpose is to provide cheap comic relief but what might have

been funny in 1961 has long since lost its humorous edge. The character's

presence is a double blow to the Asian community - not only is he fatuous and

uncomplimentary, but he is played by a Caucasian actor in heavy makeup.

Breakfast at

Tiffany's most glaring fault

was not considered a problem during the movie's initial release. However,

looking back through a 40-year window, the inclusion of the stereotyped Asian

character of Mr. Yunioshi (played by Mickey Rooney) borders on offensive. Mr.

Yunioshi's sole purpose is to provide cheap comic relief but what might have

been funny in 1961 has long since lost its humorous edge. The character's

presence is a double blow to the Asian community - not only is he fatuous and

uncomplimentary, but he is played by a Caucasian actor in heavy makeup.

Fortunately, Mr. Yunioshi is a background character, and his scenes are not plentiful enough to spoil an otherwise agreeable tone. While Breakfast at Tiffany's probably would have been a more powerful and moving story had it stuck to Capote's original storyline, there are advantages to the film's approach. The ending is a little silly and over-the-top, but, in the way of all great romantic finales, it culls a smile and a somewhat wistful sigh from nearly everyone in the audience. For those who considers themselves romantics, or for anyone who just enjoys a simple love story from time-to-time, Breakfast at Tiffany's offers a few pleasures.

Breakfast at Tiffany's (United States, 1961)

Cast: Audrey Hepburn, George Peppard, Patricia Neal, Buddy Ebsen, Martin Balsam, Villalonga, Mickey Rooney

Screenplay: George Axelrod, based on the novella by Truman Capote

Cinematography: Franz F. Planer

Music: Henry Mancini

U.S. Distributor: Paramount Pictures

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Adult Themes, Mild Profanity)

Genre: Romance/Comedy

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- (There are no more worst movies of Audrey Hepburn)

- (There are no more better movies of George Peppard)

- (There are no more worst movies of George Peppard)

- Cookie's Fortune (1999)

- (There are no more better movies of Patricia Neal)

- Ghost Story (1981)

- (There are no more worst movies of Patricia Neal)

Comments