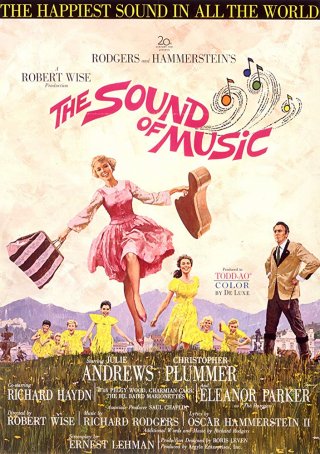

Sound of Music, The (United States, 1965)

December 15, 2018

By any reasonable critical analysis, The Sound of Music is a terrible movie. With its implausible screenplay, terrible acting, and sugar-shock mawkishness, it has all the earmarks of something that, despite its initial burst of popularity, would be forgotten by the passage of time. Yet, more than 50 years after its American premiere, the film is not only remembered but has settled into the #3 slot for all-time (inflation-adjusted) box office receipts. For many years after its theatrical run, The Sound of Music was a television staple, a guaranteed ratings-grabber. In the home video era, it has become a perennial best-seller, with new releases every 5-to-10 years (to capitalize on anniversaries). It carries the label of a “beloved classic” – a designation no one, not even the most curmudgeonly critic, is going to dispute.

The film version of The Sound of Music was an adaptation of the Rogers & Hammerstein Broadway show, which opened in 1959 and starred Mary (mother of Larry Hagman) Martin. Although the producers originally tabbed William Wyler to direct, Wyler’s involvement ended early in pre-production and the reins were handed to Robert Wise, who unexpectedly became available. Re-united with his West Side Story screenwriter, Ernest Lehman, Wise aggressively “opened up” the play, employing significant location shooting in Salzburg, Austria and allowing the 70 mm format to capture some spectacular shots of the locale. He also attempted (with limited success) to tone down the level of sentimentality and bring in more grounded elements.

Loosely based on the real-life exploits of the Von Trapp singers, a family of folk performers who attained worldwide prominence before, during, and after World War II, The Sound of Music fictionalizes all but the bare-bones details of the historical record. This caused a clash between Wise and the real-life Maria Von Trapp (played in the film by Julie Andrews), who wanted there to be “more truth” in the movie. Wise declined, saying he was making the film he wanted to make and, because she had sold the rights, she had no claim on how the story was told.

The film opens with Maria living in a convent in Salzburg.

The Mother Abbess (Peggy Wood), recognizing that the young woman may not be

suited for a cloistered life, decides that she should take on a position as a governess,

caring for the seven children of the widowed Captain Georg Von Trapp

(Christopher Plummer). Although initially nervous about the prospect, Maria

quickly grows to love the children, from the oldest, 16-year old Liesl (Charmian

Carr), who proudly declares that she doesn’t need a governess, to the youngest,

five-year old Gretl (Kym Karath). In between are the two boys, Friedrich

(Nicholas Hammond) and Kurt (Duane Chase), and three other girls, Louisa

(Heather Menzies), Brigitta (Angela Cartwright), and Marta (Debbie Turner). The

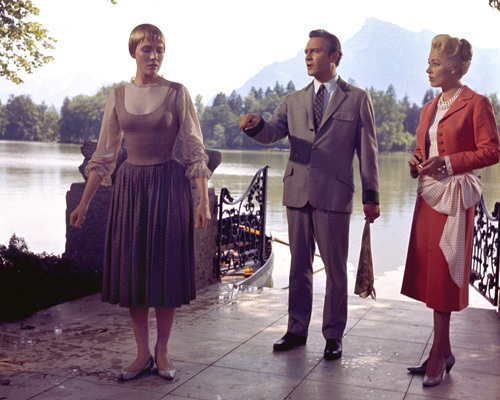

new governess clashes with the captain about discipline, playtime, and music. When

she teaches the children to sing, he is initially outraged but his anger

dissipates and he unexpectedly joins in. Although he seems destined to marry

the haughty Baroness (Eleanor Parker), he and Maria fall in love and are wed.

Shortly after their honeymoon, the Nazis come into power through the Anschluss (which happened

on March 12, 1938) and the anti-Nazi Captain Von Trapp is forced to flee the country

with his family in the dead of night.

The film opens with Maria living in a convent in Salzburg.

The Mother Abbess (Peggy Wood), recognizing that the young woman may not be

suited for a cloistered life, decides that she should take on a position as a governess,

caring for the seven children of the widowed Captain Georg Von Trapp

(Christopher Plummer). Although initially nervous about the prospect, Maria

quickly grows to love the children, from the oldest, 16-year old Liesl (Charmian

Carr), who proudly declares that she doesn’t need a governess, to the youngest,

five-year old Gretl (Kym Karath). In between are the two boys, Friedrich

(Nicholas Hammond) and Kurt (Duane Chase), and three other girls, Louisa

(Heather Menzies), Brigitta (Angela Cartwright), and Marta (Debbie Turner). The

new governess clashes with the captain about discipline, playtime, and music. When

she teaches the children to sing, he is initially outraged but his anger

dissipates and he unexpectedly joins in. Although he seems destined to marry

the haughty Baroness (Eleanor Parker), he and Maria fall in love and are wed.

Shortly after their honeymoon, the Nazis come into power through the Anschluss (which happened

on March 12, 1938) and the anti-Nazi Captain Von Trapp is forced to flee the country

with his family in the dead of night.

Careful consideration of The Sound of Music reveals an overlong film filled with artificiality and saccharine. Putting aside the performances of Julie Andrews and Richard Haydn (who employs a dry wit in playing the Von Trapp Family’s manager, Max Detweiler), the acting varies from indifferent (Christopher Plummer) to awkward and unconvincing (most of the children). Vocal decisions regarding dubbing are questionable, especially for Peggy Wood (whose singing voice is obviously provided by someone much younger) and Plummer (whose recorded vocals were later replaced). The film’s treatment of geography is no better than its sense of history since the Von Trapps’ escape journey makes no sense when one considers the relative positions of Salzburg and Switzerland. (In fact, had the Von Trapps made the crossing as depicted in the movie, they would have emerged from the Alps in Germany, not far from Obersalzberg, Hitler’s mountain retreat.)

Contemporaneous critical reaction was divided. Although some

reviewers heaped praise on the film, many of the nation’s foremost critics were

scathing. Those included The New York Times’

powerful and literate Bosley Crowther, Judith Crist, and the unflappable

Pauline Kael, who penned the following denunciation: “We have been turned into

emotional and aesthetic imbeciles when we hear ourselves humming the sickly,

goody-goody songs.”

Contemporaneous critical reaction was divided. Although some

reviewers heaped praise on the film, many of the nation’s foremost critics were

scathing. Those included The New York Times’

powerful and literate Bosley Crowther, Judith Crist, and the unflappable

Pauline Kael, who penned the following denunciation: “We have been turned into

emotional and aesthetic imbeciles when we hear ourselves humming the sickly,

goody-goody songs.”

The Sound of Music is intended to be a feel-good extravaganza – one that sweeps aside considerations of logic and intelligence in a tide of exuberance that crests with an emotional high. The songs, which have become part of the American musical lexicon, are immediately recognizable and, as Kael sarcastically acknowledged, eminently hummable. (It’s no surprise that there’s a sing-along version available.) Then there’s Julie Andrews. Coming to The Sound of Music off Mary Poppins (which hadn’t yet been released), Andrews immersed herself in the role. Her sunny disposition, powerful voice, and pure charisma dominate the movie and, at least during the musical sequences, dispel the cynical impulse. (Christopher Plummer is another matter. He famously disliked the movie to the point where he not only later referred to it as The Sound of Mucus but apparently had to be “liquored up” to film his scenes. It shows in his performance, which doesn’t represent a career highlight.)

It’s not hard to understand the movie’s appeal during its

initial four-year run, nor is it surprising that it captured five Oscars,

including Best Picture and Best Director. (The latter was Wise’s second win at

the helm of a musical, following the superior and more deserving West Side Story.) The Sound of Music represented a bastion of uplifting serenity during

a time of social upheaval. Released 18 months after JFK’s assassination and in

the midst of the civil rights turmoil, it offered escapism in its purest form.

By imprinting such positive impressions on those who saw it during the 1960s as

a child, the “rose-colored glasses” phenomenon ensured that it would cling to

an entire generation and, through family viewing, to their children and

grand-children. (The film’s ready availability through the ‘70s and ‘80s on

television and beyond that on video helped ensure that parents could share it

will their offspring – something not true of many ‘50s and ‘60s movies.)

It’s not hard to understand the movie’s appeal during its

initial four-year run, nor is it surprising that it captured five Oscars,

including Best Picture and Best Director. (The latter was Wise’s second win at

the helm of a musical, following the superior and more deserving West Side Story.) The Sound of Music represented a bastion of uplifting serenity during

a time of social upheaval. Released 18 months after JFK’s assassination and in

the midst of the civil rights turmoil, it offered escapism in its purest form.

By imprinting such positive impressions on those who saw it during the 1960s as

a child, the “rose-colored glasses” phenomenon ensured that it would cling to

an entire generation and, through family viewing, to their children and

grand-children. (The film’s ready availability through the ‘70s and ‘80s on

television and beyond that on video helped ensure that parents could share it

will their offspring – something not true of many ‘50s and ‘60s movies.)

Although I side with Crowther, Kael, and Plummer in their minority assessment of the film, I perceive its strengths. The cinematography is beguiling, the songs are uplifting, and Andrews deserves the praise and adoration she has received through the years. As for the movie as whole…suffice it to say that its power is entirely emotional. Like many crowd-pleasers that rely on nostalgia and manipulation, it works only if you are caught up in its magic. Those not ensnared in that web will recognize the artifice. For most viewers, The Sound of Music is effective and affecting – its revenue-generating power and enduring popularity are not to be gainsaid. But I must voice a rare dissent. Although I acknowledge that many treasure the film like no other, I have at best mixed feelings about The Sound of Music and cannot add my voice to the seemingly-universal chorus labeling it as a masterpiece.

Sound of Music, The (United States, 1965)

Cast: Julie Andrews, Christopher Plummer, Eleanor Parker, Richard Haydn, Peggy Wood, Charmian Carr, Heather Menzies, Nicholas Hammond, Duane Chase, Angela Cartwright, Debbie Turner, Kym Karath

Home Release Date: 2018-12-15

Screenplay: Ernest Lehman, from the stage musical book by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse

Cinematography: Ted McCord

Music: Richard Rogers & Oscar Hammerstein II, Irwin Kostal

U.S. Distributor: 20th Century Fox

- Shrek the Third (2007)

- Despicable Me 3 (2017)

- (There are no more worst movies of Julie Andrews)

- (There are no more better movies of Eleanor Parker)

- (There are no more worst movies of Eleanor Parker)

Comments