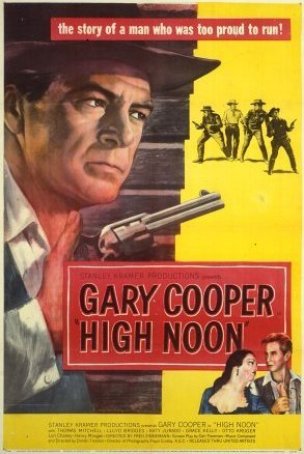

High Noon (United States, 1952)

By 1952, movie-goers knew exactly what to expect from a Western: a clean-cut, self-assured hero facing down a good-for-nothing villain in a climactic shoot-out, lots of action, gorgeous scenery, and not much in the way of thematic depth. This was a time when the Western was at the height of its popularity, and when stars of the genre, like John Wayne and Gary Cooper, were revered as heroes of the Old West. Then along came Stanley Kramer and Fred Zinnemann's High Noon, and the Western was never quite the same.

Many fans of the genre regard High Noon as the best Western ever made. There are other contenders for the titles (including, but not limited to The Searchers; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; The Wild Bunch; Unforgiven; and Dances With Wolves), but there's no debating that High Noon is amongst the elite - it is as much above the garden variety Western as something like Die Hard is above the generic shoot-'em-up action thriller.

High Noon contains many of the elements of the traditional Western: the gun-toting bad guys, the moral lawman, the pretty girl, and the climactic gunfight. But it's in the way these elements are blended together, with the slight spin put on them by Zinnemann and screenwriter Carl Foreman, that makes High Noon unlike any other Western. Audiences in the early '50s were drawn to the theater by the promise of a Gary Cooper film. Many viewers left confused, consternated, or vaguely dissatisfied, because things didn't play out in the expected way. It is rumored that John Wayne criticized High Noon's ending as being "un-American."

Indeed, 1952 was the time of "un-American" things, with Senator Joseph McCarthy wielding the power of paranoia and fear in Washington as he presided over the 20th century Salem Witch Trials. This time, the targets weren't servants of the Devil, but Communists (although some at the time might have said there was no difference). Carl Foreman, the screenwriter of High Noon, was blacklisted soon after writing the script. Also on McCarthy's list were actor Lloyd Bridges and cinematographer Floyd Crosby. To hear McCarthy tell it, High Noon was a veritable hotbed of "un-American" activity. And the story can easily be seen as allegorical -a man is turned on by those he called friends and comrades, and comes to see that the most valued principle of the masses is self-preservation.

Foreman's script was loosely based on the story "The Tin Star", by John W. Cunningham. Although there were only bare-bones similarities, Kramer bought the rights to "The Tin Star" to avoid copyright issues. Foreman fleshed out the tale using a combination of his imagination and his real-life experiences with the McCarthy Commission. The more one considers the atmosphere in which Foreman wrote High Noon, the easier it is understand the grim tone that underscores nearly every frame of the motion picture. The typical Western was a story of great heroism and derring-do. High Noon highlights much of humanity's base nature.

Cooper plays Marshal Will Kane, and, when High Noon opens, it's a little after 10 o'clock in the morning, and he is being married to Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly), a woman less than half his age. At the same time, trouble has arrived in Kane's sleepy Western town. Three outlaws, the henchmen of convicted murderer Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), are waiting at the railroad station, where Miller, recently freed from prison, is expected on the noon train. He has one goal: revenge, and the target of his hatred is Kane, the man who brought him down. Kane's friends, including the town's mayor (Thomas Mitchell), the local judge (Otto Kruger), and the former Marshal, Martin Howe (Lon Chaney), urge him to flee, but he can't. Against the wishes of his Quaker wife and with no one in the town willing to stand beside him, Kane prepares to face Miller and his gang alone.

High Noon is about loyalty and betrayal. Loyalty on Kane's part - even when everyone deserts him, he stands his ground, though it seems inevitable that the action will cost him his life. And betrayal on the town's part. Many of the locals are agreed that they owe their prosperity to Kane, but they will not help him or defend him, because they believe his cause to be hopeless. There are even those who welcome Miller's return. In the end, Kane is forced into the showdown on his own, until, at a crucial moment, Amy proves herself to be a worthy wife.

The movie transpires virtually in real time, with a minute on screen equaling one in the theater. In one of many departures from the traditional Western, there is little action until the final ten minutes, when Kane shoots it out with Miller's gang. The lone exception is a fistfight between Kane and a former deputy, Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges). Other than that, the movie is comprised primarily of Kane's failed attempts to rally the townspeople to his cause. High Noon's tension comes through Kane's desperation, aided in no small part by Elmo Williams' brilliant editing as the clock ticks down to twelve. For a motion picture with so little action, the suspense builds to almost unbearable levels.

Many have called High Noon more of a morality play than a Western, and, in some ways, that's an accurate description. Aside from the primary plot thread, there are other quandries to be considered. Amy must choose between her dearly-held peaceful beliefs (which she adopted after her brother and father were killed) and standing by her husband. It's easy to be non-violent when there's no price to pay. Harvey Pell must decide between ego and friendship. High Noon places many facets of human nature under the microscope, and therein lies the complexity in a seemingly simple idea. The deeper one looks, the more High Noon has to offer.

The climactic gunfight is not played out with two men staring down one another across an empty expanse of street, with a tumbleweed or two blowing around in the background. Instead, it's a quick and dirty business, with a hostage-taking and a man being shot in the back. When Kane wins the day, as he must (this is, after all, Gary Cooper), it has the feeling of a hollow victory. And the Marshal's final action - throwing his badge into the dirt before he and Amy ride out of town - gives us a taste of the bitterness that has settled in his mouth.

There are really only two men one could envision playing the part of Marshal Kane - James Stewart and Gary Cooper. Cooper, the older of the two men, is the better choice. He brings a world-weariness to the part. From the beginning, we sense that he's a reluctant hero, and this is confirmed as the story moves along. He admits to being afraid, and one senses that he wants nothing more than to get on the wagon with his wife and head out of town before Miller's arrival. But his overpowering sense of duty, coupled with the concern that Miller will eventually hunt him down, is strong enough to keep him where he is. Cooper imbues Kane with equal parts dignity and humanity. There's no doubt that he's a hero, but, unlike the usual Western good guy, he is filled with doubts and all-too-human weaknesses. These are the frailties each of us finds in ourselves; seeing them in Kane allows us to identify with him intimately. It makes the film more personal. In 1952, the movie was unsettling for some because they were unprepared to see a reflection of themselves on the screen. They expected an invulnerable hero; they got a man.

As important as it was to humanize High Noon's protagonist, so the villain remained largely faceless - an unseen menace riding in on the railroad tracks. Although his presence looms large over the proceedings, it isn't until the final fifteen minutes that Miller finally shows up, disembarking from the train, girded for battle. In a way, the arrival of actor Ian MacDonald is almost anti-climactic. By this point, Miller had been so thoroughly demonized that the appearance of a normal (albeit tough-looking) man is a little disappointing.

High Noon offered high-profile exposure to two actresses. Katy Jurado, a Mexican performer, received rave reviews for her tough-as-nails portrayal of Helen Ramirez, Kane's former lover. This movie represented Jurado's entré into American cinema; after High Noon, she enjoyed a nice career in Westerns, appearing in such notable films as Broken Lance (for which she earned a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination) and One Eyed Jacks. High Noon also offered the first high-billed opportunity to Grace Kelly, who would go on to capture an Oscar, the eye of Alfred Hitchcock (she became his favorite female lead), and the hearts of millions (including the Prince of Monaco). For Kelly, this certainly isn't a great performance (she is a little wooden at times), but it was enough to get her noticed.

As is true of nearly every great film, all of the elements mix together in High Noon. The black-and-white cinematography is perfect for setting the dark mood. The music is relentless. And the editing (with the possible exception of the fight between Kane and Pell, which is choppy) is nearly flawless. But the real elements to applaud are the acting, the script, and the direction, all of which are top-notch. Cooper appeared in more than 100 films during his long career; few aspired to the level of High Noon, much less attained it. And no credit on Zimmermann's resume is as impressive. The Western may be one of the few truly American art forms, and High Noon shows exactly how much potential it can embrace.

High Noon (United States, 1952)

Cast: Thomas Mitchell, Robert J. Wilke, Lee Van Cleef, Ian MacDonald, Henry Morgan, Lon Chaney, Otto Kruger, Grace Kelly, Katy Jurado, Lloyd Bridges, Gary Cooper, Sheb Wooley

Screenplay: Carl Foreman

Cinematography: Floyd Crosby

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

U.S. Distributor: United Artists

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Violence)

Genre: WESTERN

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

- Make Way for Tomorrow (1937)

- (There are no more better movies of Thomas Mitchell)

- (There are no more worst movies of Thomas Mitchell)

- (There are no more better movies of Robert J. Wilke)

- (There are no more worst movies of Robert J. Wilke)

- (There are no more better movies of Lee Van Cleef)

- Escape from New York (1969)

- (There are no more worst movies of Lee Van Cleef)

Comments