Last Days in Vietnam (United States, 2014)

July 09, 2021

If one was to clump together all the movies – both narrative and documentary – made about the Vietnam War (or, as it’s called in Asia, the American War), the number would be in the three-digit range. I have seen many of those (although by no means all) and none is quite like Last Days in Vietnam. That’s in large part because the film isn’t about starting the war, fighting the war, or losing/winning the war. It’s not about atrocities. It’s not about optics or public perception or the toll taken on those who survived their tours of duty. Instead, it’s about the end. It’s about what happened after the American public no longer cared about that small, war-torn country halfway across the globe. It’s about what happened once the troops had been withdrawn and the remaining 6000 (or thereabouts) U.S. citizens were being evacuated. It’s about things, people, and moments that have largely been forgotten by history.

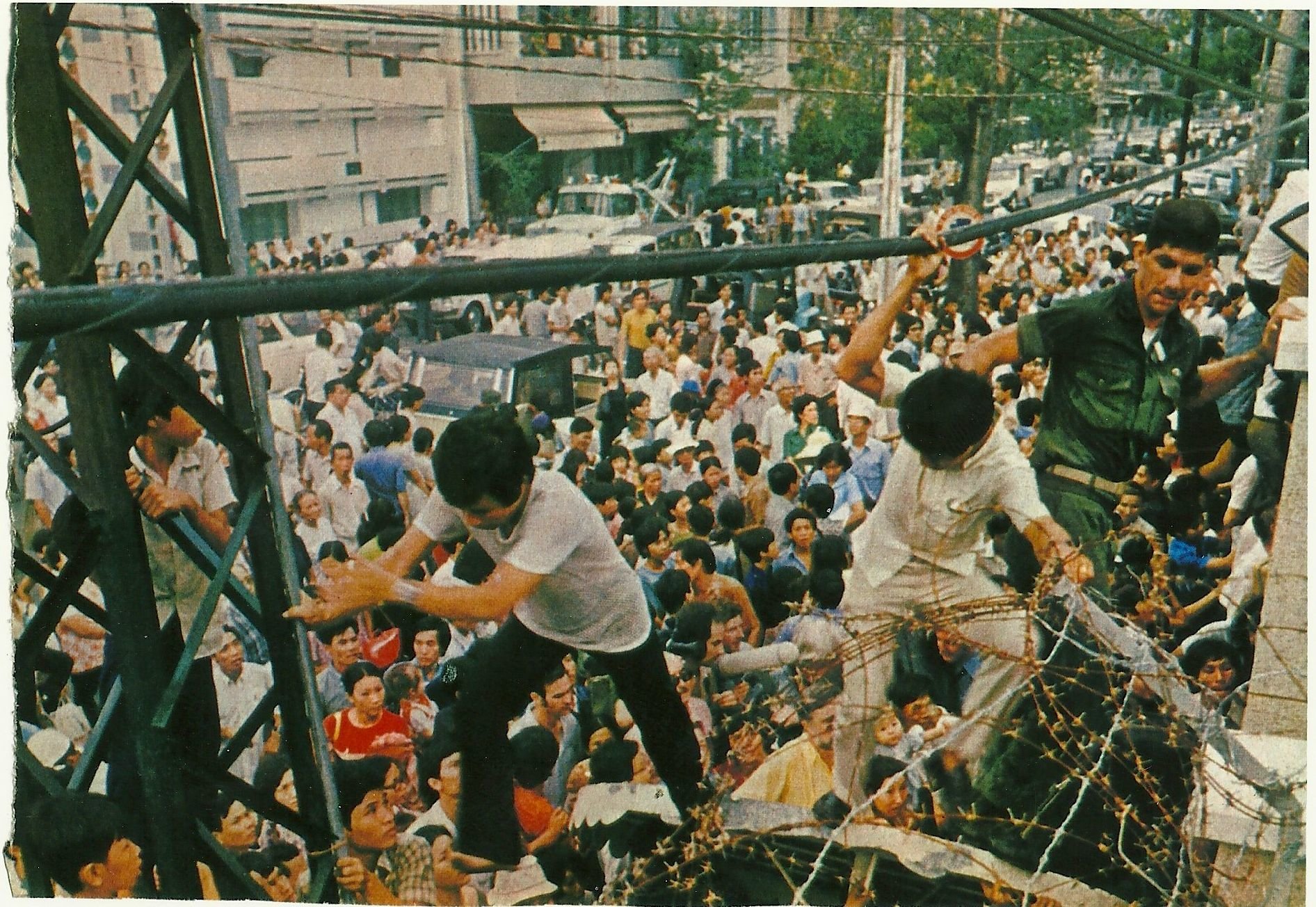

Rory Kennedy’s 2014 meticulously researched documentary targets the events of April 1975 with a specific focus on April 29-30, when Operation Frequent Wind (the codename for the helicopter evacuation of Saigon) transpired. The movie opens with a wide canvas describing the events leading up to the final month before eventually drilling down to specifics. In order to absorb the tragedy of how things ended (with more than 400 Vietnamese who believed they would be evacuated being left behind), it’s necessary to understand the politics of the situation in the United States and the mindset of Ambassador Graham Martin, who comes across as first a villain then a hero.

Refreshingly, Last Days in Vietnam doesn’t have a political

agenda. Kennedy’s goal is to present an historical document, not a screed

assigning blame. To the extent that Martin comes under the microscope for

mismanaging the early days of the evacuation (waiting too long to start

planning then delaying the execution to avoid causing panic), he is also

presented as a man of principle and personal courage and is shown to be

responsible for the large number of Vietnamese citizens airlifted out of Saigon.

Kennedy uses a mixture of current (circa 2013) interviews with key participants

(including former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger – age 90 at the time the

interview was conducted) and archival footage taken from both public and

private collections.

Refreshingly, Last Days in Vietnam doesn’t have a political

agenda. Kennedy’s goal is to present an historical document, not a screed

assigning blame. To the extent that Martin comes under the microscope for

mismanaging the early days of the evacuation (waiting too long to start

planning then delaying the execution to avoid causing panic), he is also

presented as a man of principle and personal courage and is shown to be

responsible for the large number of Vietnamese citizens airlifted out of Saigon.

Kennedy uses a mixture of current (circa 2013) interviews with key participants

(including former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger – age 90 at the time the

interview was conducted) and archival footage taken from both public and

private collections.

For most Americans, the signing of the Paris Peace Accords on January 27, 1973 (officially called the “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam”) represented an end to the conflict that had increasingly bogged down U.S. administrations since Eisenhower’s. In exchange for peace between North and South Vietnam, the United States agreed to remove all forces from the country. American military engagement ended and troop withdrawal was handled expeditiously. Many political analysts believed at the time that Vietnam’s future direction would mirror Korea’s – with a democratic south and socialist north. Then came Watergate.

The link between Nixon’s resignation and the fall of Saigon

is direct and unambiguous but it’s hardly ever mentioned in documentaries about

the subject. The North Vietnamese, believing Nixon to be a madman who might launch

a nuclear strike on a whim, stuck to the accords while he was in office. But,

once the presidency passed to Gerald Ford, they became aggressive. With the

U.S. Congress unwilling to commit additional aid to South Vietnam’s cause, it was

a foregone conclusion that the only possible resolution would be a unified

Vietnam…under North Vietnamese rule. It then became imperative to evacuate the

remaining U.S. citizens and their dependents (including Vietnamese wives and

half-Vietnamese children) and those members of the Vietnamese military and

citizenry whose American ties had turned them into “dead men walking.” When

Martin’s dithering closed off better options (like using the airport), the only

remaining way to get men, women, and children out of Saigon was via a massive, nonstop

18-hour multi-helicopter shuttle.

The link between Nixon’s resignation and the fall of Saigon

is direct and unambiguous but it’s hardly ever mentioned in documentaries about

the subject. The North Vietnamese, believing Nixon to be a madman who might launch

a nuclear strike on a whim, stuck to the accords while he was in office. But,

once the presidency passed to Gerald Ford, they became aggressive. With the

U.S. Congress unwilling to commit additional aid to South Vietnam’s cause, it was

a foregone conclusion that the only possible resolution would be a unified

Vietnam…under North Vietnamese rule. It then became imperative to evacuate the

remaining U.S. citizens and their dependents (including Vietnamese wives and

half-Vietnamese children) and those members of the Vietnamese military and

citizenry whose American ties had turned them into “dead men walking.” When

Martin’s dithering closed off better options (like using the airport), the only

remaining way to get men, women, and children out of Saigon was via a massive, nonstop

18-hour multi-helicopter shuttle.

Last Days in Vietnam avoids overt manipulation but some of the footage is designed to provoke an emotional reaction. The pain extends beyond the stranded 400+ Vietnamese left behind at the U.S. embassy to many of the U.S. officials and soldiers who had been working on the evacuation. The order came from Washington and couldn’t be ignored but it’s evident from the interviews conducted four decades after the events that some of the decisions in April 1975 have haunted them ever since. The sense of betrayal may have been more keenly felt by the fleeing Americans than the Vietnamese.

The tragic denouement of the Vietnam War is in many ways a

representation of the entire tragic, misguided affair – an example of bungling

and political gamesmanship being played by those who had no business playing it.

Kennedy lightens her damning chronicle of Operation Frequent Wind by including

moments of heroism, such as the story of a Vietnamese pilot who saved a group

of refugees then himself before ditching a chinook helicopter at sea. (It was

too big to land on the American ship that was handling the rescue.)

The tragic denouement of the Vietnam War is in many ways a

representation of the entire tragic, misguided affair – an example of bungling

and political gamesmanship being played by those who had no business playing it.

Kennedy lightens her damning chronicle of Operation Frequent Wind by including

moments of heroism, such as the story of a Vietnamese pilot who saved a group

of refugees then himself before ditching a chinook helicopter at sea. (It was

too big to land on the American ship that was handling the rescue.)

Last Days in Vietnam provides a definitive conclusion to a saga that many incorrectly believed to have ended two years earlier. The amount of footage collected by Kennedy gives a life and urgency to the proceedings that was absent in the United States at the time it was happening. This is history unfolding in real-time, even if it has taken more than four decades for it to come to light. Those who seek to fully understand what the Vietnam War meant are encouraged to watch all the best-known narrative films set during the conflict (Apocalypse Now, Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, etc.) as well as some of the more comprehensive documentaries (such as Vietnam in HD or The Vietnam War by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick). Last Days in Vietnam should be included in such a “must see” list as the definitive account of the coda. This isn’t a “big picture” movie in that it doesn’t seek to answer questions that are beyond its limited scope but, within the parameters established by Kennedy and her writers, it leaves few stones unturned.

Last Days in Vietnam (United States, 2014)

Cast: Henry Kissinger, Richard Armitage, Frank Snepp, Stuart Herrington, Terry McNamara

Home Release Date: 2021-07-09

Screenplay: Keven McAlester, Mark Bailey

Cinematography: Joan Churchill

Music: Gary Lionelli

U.S. Distributor: American Experience Films

U.S. Release Date: 2014-01-17

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Violence)

Genre: Documentary

Subtitles: In English and Vietnamese with subtitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.78:1

- (There are no more better movies of Henry Kissinger)

- (There are no more worst movies of Henry Kissinger)

- Hobbit, The: The Battle of the Five Armies (2014)

- Hobbit, The: An Unexpected Journey (2012)

- Into the Storm (2014)

- Ocean's Eight (2018)

- Hobbit, The: The Desolation of Smaug (2013)

- (There are no more worst movies of Richard Armitage)

- (There are no more better movies of Frank Snepp)

- (There are no more worst movies of Frank Snepp)

Comments