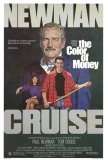

Color of Money, The (United States, 1986)

June 10, 2009

The Color of Money is a good movie, but perhaps not a good sequel. In revisiting the shady, obsessive world of former pool shark Fast Eddie Felson (Paul Newman), Martin Scorsese provides us with a character so different from the one found in Robert Rossen's 1961 classic, The Hustler, that it might be another person. The film works as the study of an apprentice who outgrows the teacher and of a middle-aged man gripped by the compulsion of his youth, but it's less successful as an opportunity to catch up with Fast Eddie 25 years later. Decoupling the films offers the best way to appreciate the follow-up. The Color of Money plays better when not under the shadow of The Hustler, which is ultimately a better and more compelling tale.

At the end of The Hustler, after beating his rival Minnesota Fats, Fast Eddie walked out of the pool hall and into a different life. He channeled his energy and charisma into selling liquor and, by the time we meet him at the beginning of The Color of Money, he's wealthy and content. The hunger is gone. He hasn't picked up a pool cue in a quarter-century and shows no desire to do so again. Then, a chance encounter at a bar owned by his part-time lover, Janelle (Helen Shaver), brings him into contact with young hotshot Vincent Lauria (Tom Cruise) and his girlfriend, Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio). Vincent is a hustler with more raw talent than Eddie has seen in years. He's a natural "flake," meaning he has the kind of personality that will allow him to be not taken seriously until it's too late. Vincent would rather play video games, but Eddie notices immediately that he could make a fortune playing pool. Eddie and Carmen come to a business arrangement: together, they'll manipulate and mold Vincent into the kind of player he needs to be to win big at a Nine Ball Tournament in Atlantic City.

For a while, the story unspools as one might expect from a movie about an upstart and the veteran who harnesses his wildness. It is, after all, an old story. But in this version, the mentor fails the student and they part ways. Eddie abandons Vincent, leaving the young firebrand and Carmen to make their way alone to Atlantic City. The pool bug has once again bitten Eddie; the first time we see shades of the character who inhabited The Hustler is during a series of matches between Eddie and a young shark (Forest Whitaker) who embarrasses the old-timer. This compels Eddie to start practicing. By this time, it's a foregone conclusion that he and Vincent will meet across a table in Atlantic City, but the way the story evolves from there is anything but predictable.

The screenplay for The Color of Money, penned by legendary screenwriter Richard Price, takes loose inspiration from the 1984 novel by Walter Tevis (who was also the author of the source material for The Hustler), but changes so much of the story that the plot is virtually unrecognizable. In the book, Fast Eddie goes on tour with Minnesota Fats for a cable TV program and, through the competitions with his old rival, he regains his self-esteem. Little of that remains in Price's interpretation of where Fast Eddie's life would take him.

Although the character of Fast Eddie is richer in The Hustler than in The Color of Money, one can make an argument that Paul Newman's performance is more nuanced in the latter film than in the former one. The Hustler does not represent Newman at his finest (although he, George C. Scott, Jackie Gleason, and Piper Laurie, received nominations), but it's a solid example of acting. Newman's mature interpretation of Fast Eddie in The Color of Money is a more accomplished portrayal. It's not the best work of Newman's career (that probably came in either Hud or Cool Hand Luke), but it earned him an Oscar on the seventh try. Most people consider The Color of Money's Best Actor statuette to be a "Career Award" (as was the case with Al Pacino in Scent of a Woman), but when one considers the competition (Dexter Gordon in 'Round Midnight, William Hurt in Children of a Lesser God, Bob Hoskins in Mona Lisa, and James Woods in Salvador), it's not an outrageous win. (Ironically, Newman was not on hand to accept the award.)

Financially, The Color of Money was successful - more successful than any other Scorsese film to that point. (Not until Cape Fear would the filmmaker achieve a bigger score.) It made back about five times its cost, with older movie-goers attending because of Newman and younger viewers lured to theaters by Tom Cruise. In 1986, Cruise was at the height of his popularity, with Top Gun having been one of the summer's big hits, and his box office impact for The Color of Money could not be discounted. His performance is unremarkable - he's a shallow, cocky ass without a lot of depth. It's an adequate portrayal, but there's no question who commands the screen when Cruise and Newman share it. Carmen, played by up-and-coming actress Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio (in her follow-up to Scarface), is a more interesting character. This, along with James Cameron's The Abyss, provides the best exposure of Mastrantonio's talents.

The Color of Money is even less of a sports film than its predecessor. It's about the characters and their relationships. A sport (or game) is merely the means by which those relationships are facilitated. Scorsese goes out of his way to avoid showing extended pool sequences (there's nothing to match the all-night-all-day duel between Fats and Fast Eddie in The Hustler) and the film ends with the promise of matches that will never be depicted. In fact, Scorsese goes out of his way to toy with the audience's expectations. In a traditional telling of the story, The Color of Money would have climaxed with the showdown between Vincent and Fast Eddie in the finals of the Atlantic City tournament. Here, that happens in an early round and leads to a downbeat and subdued result. The Color of Money isn't concerned with retreading sports clichés; it's interested in the characters and how they react during certain circumstances.

The Color of Money represents the only sequel Scorsese has produced (at least do date). He has made genre films, exploitation flicks, and even tried his hand at remakes but, outside of this picture, he has avoided sequels. The reason he agreed to embark upon this journey was twofold: the opportunity to direct Paul Newman and the belief that The Color of Money was atypical in that it could be seen with 100% comprehension by someone who was ignorant of the existence of The Hustler. Indeed, of all the countless sequels churned out by Hollywood over the years, this may be the best at standing on its own. That, in and of itself, is an accomplishment.

When considered within the context of Scorsese's oeuvre, The Color of Money is a relatively minor effort - not forgettable but far from the level the director has achieved with his best work (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, The Departed). The film's style is subdued, with Scorsese limiting his trademark visuals and flourishes. In fact, not since the made-for-hire Boxcar Bertha (which preceded his "true" debut, Mean Streets) has a movie fashioned by Scorsese seemed less like the product of the director. The picture will forever be most remembered for providing Newman with his one and only non-honorary Oscar and for giving him a chance to re-invent a character he gave birth to 25 years earlier. The Fast Eddie of The Color of Money may not recall his earlier incarnation but the way in which he evolves during the course of this movie allows us to wonder how different we will be in a quarter century.

Color of Money, The (United States, 1986)

Cast: Paul Newman, Tom Cruise, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Helen Shaver, John Turturro, Bill Cobbs

Screenplay: Richard Price, based on the novel by Walter Tevis

Cinematography: Michael Ballhaus

Music: Robbie Robertson

U.S. Distributor: Touchstone Pictures

U.S. Release Date: 1986-10-17

MPAA Rating: "R" (Profanity, Nudity, Violence)

Genre: DRAMA

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- Twilight (1998)

- (There are no more worst movies of Paul Newman)

- Scarface (1983)

- (There are no more worst movies of Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio)

Comments