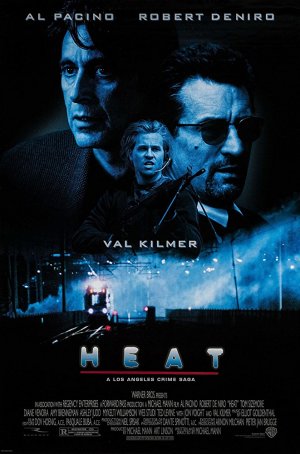

Heat (United States, 1995)

December 17, 2017

Here’s a link to my original review of Heat, published in December 1995.

At the time of its 1995 release, Heat was heralded primarily as offering the first on-screen pairing of legends Al Pacino and Robert De Niro. Although the two had shared top billing for The Godfather Part II, the nature of that film ensured they wouldn’t appear together. Although the Pacino/De Niro interaction was Heat’s top selling point, they had only two scenes together, totaling perhaps ten minutes. Thirteen years later, they would again collaborate on Jon Avnet’s Righteous Kill, where they were together considerably more often. Although Righteous Kill was inferior in almost every way to Heat, its existence reduces to a footnote the 1995 film’s claim-to-fame. However, taking the focus off the Pacino/De Niro sequences and allowing the movie to stand on its own reveals a production of uncommon power and intensity.

Heat looks at both

sides of the law as it chronicles an armored truck robbery and the subsequent

fallout. With typical precision, Mann builds tension not through contrivances

but through character identification and the ever-present prospect of violence.

Everything in Heat builds to a

climactic confrontation that occurs with nearly an hour still remaining.

Employing a forceful (but not overbearing) score by Elliot Goldenthal,

evocative imagery by the legendary Dante Spinotti, and top-notch acting by a

dream cast, Mann works his magic to fashion an epic crime story out of a

seemingly standard-order story.

Heat looks at both

sides of the law as it chronicles an armored truck robbery and the subsequent

fallout. With typical precision, Mann builds tension not through contrivances

but through character identification and the ever-present prospect of violence.

Everything in Heat builds to a

climactic confrontation that occurs with nearly an hour still remaining.

Employing a forceful (but not overbearing) score by Elliot Goldenthal,

evocative imagery by the legendary Dante Spinotti, and top-notch acting by a

dream cast, Mann works his magic to fashion an epic crime story out of a

seemingly standard-order story.

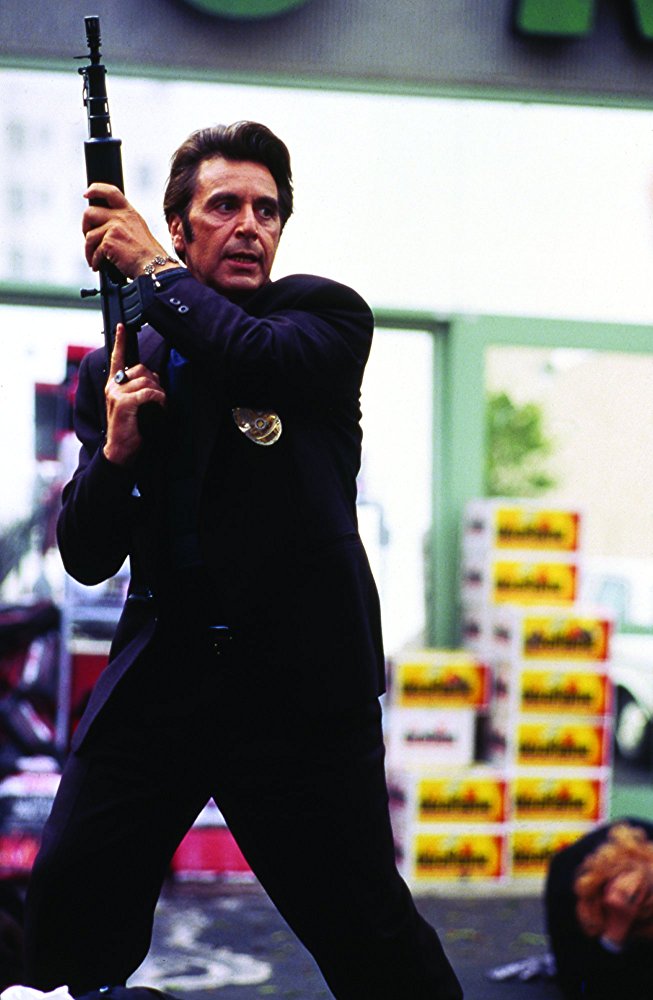

The movie is constructed almost like a chess match, with Al Pacino’s tenacious investigator Lt. Vincent Hanna as one king and Robert De Niro’s master criminal Neil McCauley as the other. Heat shows all their moves and countermoves and, although in retrospect it might seem that the checkmate is inevitable, it doesn’t feel that way while watching the movie. Both characters are too clever, too dogged to be outsmarted.

Vincent’s job is to investigate a series of crimes committed by Neil's group of trained, experienced robbers. These include Val Kilmer’s Chris, Tom Sizemore’s Michael, and Kevin Gage’s Waingro, whose penchant for violence gets him kicked off the team. With the cops closing in, the criminals have decided to call it quits after one more big-time job. Meanwhile, both men – the “good” guy and the “bad” guy - are having personal problems. Vincent's marriage is falling apart as his wife (Diane Venora) has finally decided that she doesn’t want to be in a relationship where she places second to her husband’s job. Neil, after decades of loneliness nursing a creed about the importance of not forming close connections, has finally found a woman (Amy Brenneman) with whom he is sympatico.

Mann’s movies are never strictly about story. Narrative is

important to the director but it’s just one weapon in his arsenal. He’s equally

concerned about dialogue, mood, and look. None of these aspects is given

precedence. To Mann, they’re equally critical elements necessary to making the

movie work. Heat isn’t a perfect

synthesis but it’s close. The film looks good and the feel is electric. When

Pacino is on screen, the viewer is riveted. When De Niro is on screen, the same

is true. And, during the classic scene when they share the camera’s gaze,

Mann’s dialogue takes second place to the subtle ways in which the two great

actors (both at the top of their game at the time) interact.

Mann’s movies are never strictly about story. Narrative is

important to the director but it’s just one weapon in his arsenal. He’s equally

concerned about dialogue, mood, and look. None of these aspects is given

precedence. To Mann, they’re equally critical elements necessary to making the

movie work. Heat isn’t a perfect

synthesis but it’s close. The film looks good and the feel is electric. When

Pacino is on screen, the viewer is riveted. When De Niro is on screen, the same

is true. And, during the classic scene when they share the camera’s gaze,

Mann’s dialogue takes second place to the subtle ways in which the two great

actors (both at the top of their game at the time) interact.

When I first reviewed Heat upon its release in 1995, I provided a list of problems that I believed to have limited the film’s effectiveness. To be fair, I still think most remain valid but I no longer see them as having as the same degree of impact. They are small blemishes not the grotesque distortions they seemed to me 22 years ago. Perhaps at the time, I was blinded by the cinematic significance of the Pacino/De Niro meeting or maybe the movie’s length caused me to lose focus. (Heat is too long – shortening scenes and cutting subplots could have tightened things considerably.) Whatever the case, the intervening years have allowed me to take a fresh look at the film and come up with an enhanced appreciation.

So what are Heat’s shortcomings? Most have something to do with Mann trying to do too much – an admirable flaw but a flaw nonetheless. There are too many characters and the script wants to spend time filling in background for each of them. Some of the character-building information is clichéd and there are times when the surfeit of exposition kills momentum. One example: although the scenes featuring Dennis Haysbert’s Donald Breedan are well-acted, they are largely extraneous. The character’s role turns out to be insignificant yet about 10 minutes is spent sketching out his backstory.

What a cast! The names are no less impressive today than

they were when the movie was released. Some of the actors, like Pacino and Val

Kilmer, have lesser profiles in 2017 than in 1995 but others, like Natalie

Portman, have risen to impressive heights. Heat

is an actors’ clinic – a tour de force for more than one performer. Obviously,

the lion’s share of the screen time is given to Pacino and De Niro and neither

disappoints. This was at a time when Pacino was huge and De Niro hadn’t started

doing the comedies that would change how the public viewed him. Whether apart

or together, these two commanded the viewer’s attention with their intensity

and attention to detail. Pacino gets a “Pacino moment” (the scene where he

confronts his wife’s lover) and De Niro is given more than one opportunity to

display the slow, simmering anger that defined his early performances.

What a cast! The names are no less impressive today than

they were when the movie was released. Some of the actors, like Pacino and Val

Kilmer, have lesser profiles in 2017 than in 1995 but others, like Natalie

Portman, have risen to impressive heights. Heat

is an actors’ clinic – a tour de force for more than one performer. Obviously,

the lion’s share of the screen time is given to Pacino and De Niro and neither

disappoints. This was at a time when Pacino was huge and De Niro hadn’t started

doing the comedies that would change how the public viewed him. Whether apart

or together, these two commanded the viewer’s attention with their intensity

and attention to detail. Pacino gets a “Pacino moment” (the scene where he

confronts his wife’s lover) and De Niro is given more than one opportunity to

display the slow, simmering anger that defined his early performances.

In the final analysis, Heat is very much “a Michael Mann film”, with all the many positives (and the few negatives) that go along with that designation. Like Terrence Malick, Mann is often more about style than substance, although (unlike Malick) he never abandons the latter in favor of the former. Heat is awash in blues and blacks, uses close-ups to enhance intensity, and allows each of the actors – even those with the smallest of supporting roles – a moment or two to shine. Under a director with less vision and ambition, Heat could have been just another routine crime drama but Mann brings such an edge to the proceedings that the threadbare story takes on a new urgency.

Heat (United States, 1995)

Cast: Al Pacino, Natalie Portman, William Fichtner, Dennis Haysbert, Ted Levine, Wes Studi, Mykelti Williamson, Ashley Judd, Amy Brenneman, Diane Venora, Tom Sizemore, Jon Voight, Val Kilmer, Robert De Niro, Kevin Gage

Home Release Date: 2017-12-17

Screenplay: Michael Mann

Cinematography: Dante Spinotti

Music: Elliot Goldenthal

U.S. Distributor: Warner Brothers

U.S. Release Date: 1995-12-15

MPAA Rating: "R" (Violence, Profanity, Sexual Content)

Genre: Thriller

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1

- Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005)

- V for Vendetta (2006)

- Star Wars (Episode 1): The Phantom Menace (1999)

Comments